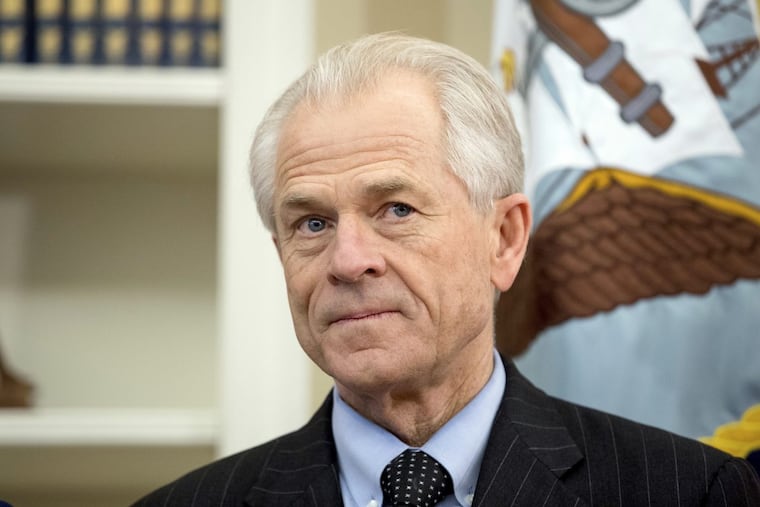

Here's how Peter Navarro, Trump's tariff booster, wants to protect America

For protectionists like Trump adviser Navarro, foreign investment in U.S. producers, employers and real estate "is bad because there will be more foreign ownership of U.S. assets"

Peter Navarro, the Harvard Ph.D. economist who heads President Trump's National Trade Council, has alarmed business-oriented Republicans with his "protectionist views on trade, especially given the negative effects that they could have on the economy and the financial markets," writes economist and investor Ed Yardeni in his daily client letter Thursday.

With Goldman Sachs alumnus Gary Cohn resigning as Trump's pro-corporate economic adviser, Navarro "seems to be gaining influence" as an intellectual author of the 25 percent steel import tariffs (and 10 percent aluminum tariffs) that Trump imposed. So Yardeni summarized Navarro's March 6 keynote speech and discussion before what Yardeni called a "disagreeable crowd" of skeptical economists at the National Association for Business Economics. Highlights:

Navarro sees foreign investment in the U.S. as bad. Yardeni quotes him: "Any deficit in the current account caused by imbalanced trade must be offset by a surplus in the capital account, meaning foreign investment in the U.S."

Yardeni translates: "In other words, the dollars traded for America's imports will come back to the U.S. in the form of foreign direct investment. For [investment markets], that's good because the demand for capital should push interest rates down and stocks and employment up. But for protectionists [such as Navarro], that's bad because there will be more foreign owners of U.S. assets."

So "conquest by purchase is Navarro's ultimate concern." As in, conquest of U.S. industry, by foreign purchasers. (Yardeni credits investor Warren Buffett with coining that phrase, "conquest by purchase.")

Navarro's premise is that running "large and persistent trade deficits" results in "a pattern of wealth transfers offshore," with foreigners pocketing profits from their U.S. investments, instead of Americans.

That's the opposite of the mainstream business view, which is that it's good to have foreigners injecting money into the U.S. economy, employing people here, and driving up stock and asset values here — instead of investing that money back in their own countries, in assets that would compete with ours.

Are you old enough to remember the 1980s-era worries about Japanese buying prime U.S. real estate and businesses in the 1980s? Pop culture works Michael Crichton's 1992 novel Rising Sun, and the lurid movie made from it, warned that "unfair competition" was turning America into a colony. But Japan still hasn't taken over the world, nor did Britain before it; we are still richer and have wider influence than China, the current focus of much popular concern.

Navarro remains worried about other countries' investors buying "America's companies, technologies, farmland, food-supply chain" and, finally, controlling "much of the U.S. defense-industrial base."

Navarro looks back to manufactured products as the source of American security, not forward to services, which the U.S. exports in this digital age. Navarro reiterates that "a strong manufacturing and defense industrial base is the very bedrock for America's national security."

He noted that the U.S. military depends on a single company to fix submarine propellers, and on foreigners for aspects of aircraft electronics. So Navarro says Trump's trade policy goal should be nationalist: to "reclaim all of the supply chains and manufacturing capabilities that would otherwise exist if the playing field [were] level."

That's the other complaint — besides national security and foreign profit-taking: The other side doesn't play fair: "Free, fair, reciprocal trade" is "the trade motto of the administration, according to Navarro, who repeated it at least four times during the NABE conference," Yardeni reports.

As examples of unfair trade practices, "Navarro cited non-tariff barriers on imported goods in Japan, tariffs on imports to India, unfairly biased rebates to German exporters, and the dumping of goods through Vietnam and Thailand by Chinese state-owned enterprises and Korean conglomerates. Navarro also criticized the practice in China of requiring foreign business owners to establish 50 percent Chinese ownership through joint ventures, putting domestic intellectual property at risk."

Maybe it's not that bad. "The silver lining for investors is that Navarro claims the intent of the administration's tough stance on trade is simply to 'encourage our trading partners to lower' their tariffs and barriers to trade. So the latest tariffs slapped on our trading partners may be negotiable for the U.S. That now seems especially likely, given the pushback that the president is getting for supporting Navarro's trade approach."

But lately, Yardeni suggests, "the swift resignation of Gary Cohn following Trump's announcement that he would impose tariffs on aluminum and steel" is a sign that compromise might not really be the goal here: "Navarro previously reported to Cohn. [But] White House Chief of Staff John Kelly in September folded Navarro's Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy into the Cohn-led National Economic Council," which temporarily isolated Navarro under the more internationalist and mainstream-corporate Cohn. "With Cohn out of the picture now, it seems to us that Navarro may soon be sitting closer to Trump both figuratively and literally at the trade table."