Tariff wars: Whose stocks are hurting more, U.S. or China?

"China has more to lose from this. We call a 10 percent stock-price drop a 'pullback'. But they are more levered, and they have a lot of government activity in their stock exchanges, so if their markets come under too much pressure, [China stock prices] will fall apart."

So far, the U.S.-China trade fight is going worse for China, if stock prices are any sign. Companies in the MSCI China index fell 12 percent in the two weeks since President Trump posted new tariffs vs. 3 percent for the S&P 500.

"China has more to lose from this," Dan David, co-owner of Skippack-based GeoInvesting (and the Republican nominee for Congress in Montgomery County) told me. "We call a 10 percent stock-price drop a 'pullback.' But they are more levered [with investor debt], and they have a lot of government activity in their stock exchanges, so if their markets come under too much pressure, [China stock prices] will fall apart," especially at China's current price-to-earnings ratios, which are even higher than the S&P 500.

"That's why China last week put out short-sale restrictions again, and is telling brokers to hold stocks."

Still, David says America would do better with a more carefully targeted China trade policy. Washington would do more to help U.S. retailers, for example, by pushing to equalize postal rates, which David said are much higher from the U.S. to China than the reverse.

Vanguard Group, the Malvern investment giant, "sees the odds of a true global trade war as having risen to about 1 in 3, up from 1 in 10 a few weeks ago," the company told clients in a report last week. Vanguard says protective tariffs could briefly boost U.S. industries, but a full-blown "trade war environment could reduce U.S. [gross domestic product] by 1.7 points" and also boost inflation, putting pressure on the Federal Reserve to further boost interest rates and leaving the U.S. "in a lagging position" in arranging future economic and political alliances around the world.

By contrast, Chinese consumers actually have little to lose from escalating tariffs, argues Andy Rothman, investment strategist for $35 billion-asset Matthews Asia, one of the largest U.S. investors in Chinese stocks, in a report to clients from Beijing last week. Matthews is partly owned by Radnor-based Lovell Minnick Partners.

The new U.S. tariffs on Chinese exports will likely cut China national production by just 0.1 percent, because they will affect only "about 2 percent of all Chinese exports," according to Rothman. As a result, tariffs would likely slow China's growth "much less than many expect," to around 6.7 percent from a previously-projected 6.8 percent. Rothman expects China will be able to pass much of its U.S. tariff costs to companies from Japan, Korea, and Germany, which use Chinese factories to export to the U.S.

Rothman hopes it doesn't get that far: He suggests Trump could now "claim that the tariffs delivered on his campaign pledge to get tough on China, and then move on to negotiations over issues that really matter to U.S. companies, such as better protection of intellectual property and market access in China."

There's a cost to Trump for escalating the trade fight, he added: China has targeted its retaliatory tariffs to "Trump supporters, such as soybean farmers, which could help Democrats take control of the House in November." China president Xi Jinping could also stall Trump's outreach to North Korea.

China's increasingly consumer-driven economy won't much notice U.S. tariffs, according to Tiffany Hsiao, portfolio manager at Matthews Asia. "China's consumers will continue to look for ways to improve their quality of life and will seek out brands that cater to their tastes and aspirations," she predicted. And China will continue to subsidize and support new industries, including computer semiconductors and biotech (including investments in U.S. companies), and may boost its support for those industries in case of a trade war.

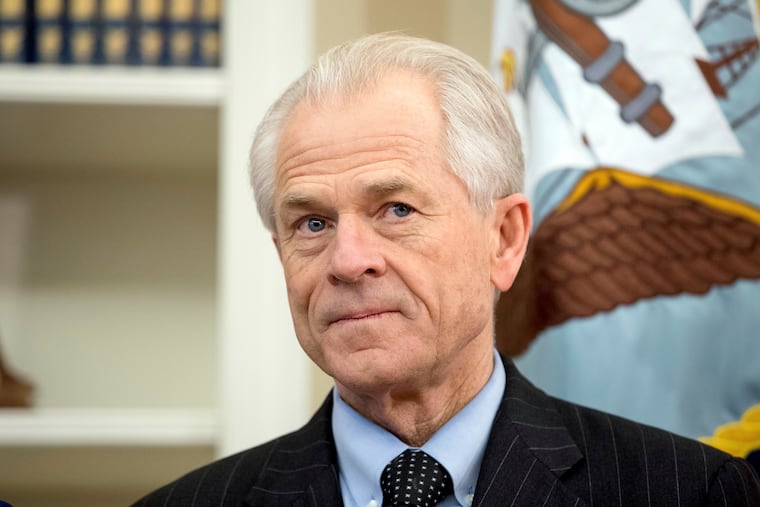

In that scenario, China's protectionist and favored-industry goals resemble Trump administration goals, as sketched by Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro on CNBC last week: He said the goal of Trump's trade, tax, and energy policies is to convince other countries to end their own unfair trade practices — and to end up with more Americans working "with their hands" in factories, enabling the U.S. to develop "a very dominant lead in the emergency industries of the future — artificial intelligence, robotics, high-tech shipping, extreme manufacturing."