Hospitals rush to provide costly proton beam therapy

Technological advances are a major factor in rising U.S. health-care spending. Often, they lead to better care for patients. But now, nonprofit hospitals and private investors across the country are spending fortunes to build a wave of expensive, high-tech proton-beam cancer treatment centers before researchers have established that the treatment works better than cheaper alternatives for many types of cancer.

Technological advances are a major factor in rising U.S. health-care spending. Often, they lead to better care for patients.

But now, nonprofit hospitals and private investors across the country are spending fortunes to build a wave of expensive, high-tech proton-beam cancer treatment centers before researchers have established that the treatment works better than cheaper alternatives for many types of cancer.

Grassroots support for proton therapy is especially strong among victims of prostate cancer who say the treatment has spared them the nasty side effects of impotence and incontinence associated with surgery and other common treatments.

Skeptics, however, say that in the absence of long-term studies proving that proton beams work better — beyond what has been proven for a narrow range of cancers — than alternatives that cost half as much, the proton phenomenon is a prime example of the medical arms race that helps drive health-care spending ever higher.

"As long as these guys are collecting the money, they don't have an incentive to prove it's better," said Ezekiel J. Emanuel, chairman of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine. Emanuel's ire centers on the use of proton beams for prostate cancer at $50,000 a pop.

That's "way too much. That's what I'm against," Emanuel said.

Stephen Hahn, chairman of the department of radiation oncology at Penn, called the controversy a "healthy discussion" and said esearch was integral to efforts at Penn's Roberts Proton Therapy Center. "It is still relatively unexplored what kinds of patients benefit from proton therapy," Hahn said.

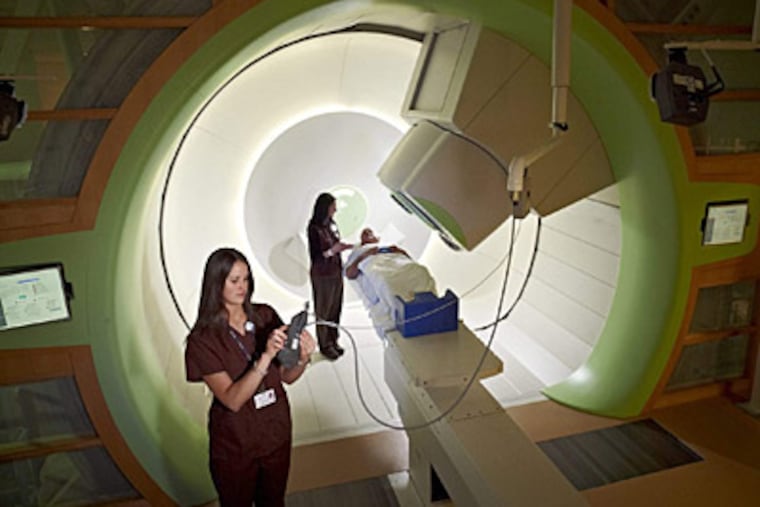

The theory behind the therapy is that protons can be directed more precisely than traditionalX-rays to hit tumors, reducing the damage to surrounding tissues.

The process requires a 220-ton particle accelerator in a concrete bunker with walls five feet thick to propel the protons to two-thirds the speed of light. The cost to build a proton center ranges from about $100 million to more than $200 million.

The payback can be substantial.

At the Florida Proton Therapy Institute Inc., an affiliate of the University of Florida in Jacksonville, which opened in 2006, the operating profit margin was 26 percent for the year ended June 30. That is huge compared with general hospitals, which are lucky to have operating profits of 5 percent.

The University of Pennsylvania opened the Mid-Atlantic's first proton-beam therapy center in early 2010 at a cost of $144 million, sparing the nearly 500 patients it has treated so far a trip to the proton center in Jacksonville or one of the five other centers open then.

But the field of proton therapy is getting more crowded, with 10 in operation and several under construction.

The $225 million Hampton University Proton Therapy Institute opened in August 2010 in southern Virginia. Procure Treatment Centers Inc., a for-profit company, opened a $160 million proton center last month in Somerset, N.J.

Ground was broken this month on a $200 million center in Baltimore that will be operated by the University of Maryland School of Medicine but owned by private investors who had invested $33 million as of January.

Further afield, Scripps Health in San Diego is in a partnership with private investors for a $225 million center that is under construction. The Mayo Clinic started construction last year on two proton centers, one in its home state of Minnesota and another in Arizona. Total cost is $370 million.

Foundation work was finished last week on a $119 million proton center in Knoxville, Tenn. About 20 others are either under development or on the drawing board.

Jeff Bordok, president and chief executive of Advanced Particle Therapy, a Nevada company that is developing the proton centers in San Diego and Baltimore, said there was plenty of room for more proton centers in the market. With the capacity to treat 2,000 patients a year, for example, the Baltimore center could handle only 15 percent of the people in the greater Baltimore area — up to the edge of the Philadelphia region — who could benefit from proton therapy, Bordok said.

The Procure Treatment Center in New Jersey, in partnership with the CentraState Healthcare System in Freehold and Princeton Radiation Oncology, which has five offices in central New Jersey and one in Langhorne, was designed to tap into the huge New York market. The center was treating 12 patients last week, with one of four treatment rooms in operation.

With the capacity to treat 1,500 patients a year, the center would need to attract roughly half that to break even, depending on the mix of treatments, center president James Jarrett, who worked in private equity before joining Procure in 2005, said in February at a media open house.

Despite a slower start than anticipated, Penn's Roberts proton center "is meeting our budgetary expectations," said Ralph Muller, chief executive of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, though he provided no specifics.

Cancer treatment accounts for more than $500 million in annual revenue at Penn, Muller said. "The proton therapy is an important and essential part of what we do, but it's a relatively small part of what we do," Muller said.

Some cancer victims who have had proton therapy are thrilled with the results and have become volunteer ambassadors for it.

That group includes Bucks County resident Mark T. Podob, who was treated at Penn in the summer of 2010. "I had absolutely no side effects and continue to have no side effects," said Podob, 61, referring to what he called the "bad actors" associated with prostate treatments, such as incontinence, impotence, and rectal bleeding.

Podob's insurance plan, Independence Blue Cross's Personal Choice, paid for the proton treatment with no questions asked, he said.

IBC would not discuss what it pays for proton treatment of prostate cancer. Medicare pays between $40,000 and $50,000, industry sources said. The Medicare payment for a more common radiation treatment for prostate cancer averages $22,671 in hospital outpatient clinics, according to Revenue Cycle Inc., an Austin, Texas, oncology consulting firm.

IBC covers proton-beam therapy for prostate cancer while in its written policy acknowledging a lack of "evidence to suggest that it is clinically superior" to other treatments. "Our challenge is balancing the interest in providing coverage for what is held out to be state-of-the-art therapy and being a responsible steward of the health-care resources our customers entrust us with," said Don Liss, a senior medical director and vice president for clinical programs and policy at IBC. "This is a tough one."

Clinical trials of the sort that could prove or disprove the benefits are under way, but Diane Robertson, director of the health technology assessment information service at the ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, expressed doubts about their chance of finding enough patients to participate. Robertson wrote ECRI's first technology assessment of proton therapy in 1997.

"It's good that we have these clinical trials ongoing, but, guess what? I predict they are going to have trouble accruing patients to these randomized control trials because the therapy is already out there," Robertson said. "If you're a patient, you're not going to want to enter a trial when you have a belief" that protons are superior.

Contact Harold Brubaker at 215-854-4651 or hbrubaker@phillynews.com.