After upgrades to its Center City power plant, Veolia rebrands its energy as ‘green steam’

The Center City steam loop, source of the Dickensian sidewalk vapor clouds that have warmed the soles of generations of pedestrians, does not normally evoke images of a modern energy system.

The Center City steam loop, source of the Dickensian sidewalk vapor clouds that have warmed the soles of generations of pedestrians, does not normally evoke images of a modern energy system.

But in the last two years, the system's owner, Veolia Energy, has quietly upgraded its century-old power plant in Grays Ferry to reposition the nation's third-largest district heating system as an environmentally friendly energy source. Veolia is calling it "green steam."

On Monday, Mayor Nutter and Robert F. Powelson, chairman of the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission (PUC), will inaugurate Veolia's $60 million upgrade, which the Mayor's Office praises for reducing the city's greenhouse gas emissions.

By installing new natural gas boilers and expanding the pipeline that delivers gas to the plant, Veolia will virtually eliminate the plant's use of high-sulfur fuel oil to produce steam for the system's 300 customers, including some of the city's most prominent buildings.

Natural gas costs less than fuel oil, so the bills for Veolia's customers should decrease. And natural gas burns more cleanly than oil, so the plant will emit 93 percent less sulfur dioxide, 20 percent less nitrogen oxide, and 70,000 fewer metric tons of greenhouse gases a year.

Veolia is marketing the improvements to property owners who face increasing pressure to be more environmentally conscious. Under a new city law, large commercial buildings must report their energy consumption to government, which will "benchmark" properties for efficiency. Veolia customers will be able to take credit for a share of the efficiency improvements.

"It really helps the customers achieve their goals of efficiency and emissions reductions," said Michael J. Smedley, Veolia's Mid-Atlantic vice president.

The improvements were driven partly by Veolia's biggest customer, the University of Pennsylvania, which consumes 40 percent of Veolia's output.

According to filings with the PUC, Penn was exploring options to generate its own steam to lower its costs and achieve its climate-action goals. Veolia proposed the upgrades to woo Penn to renew its supply contract for 20 years.

"To me, the message of this story is that institutions can use their buying power to work with suppliers to advance common strategies, common philosophies," said Anne Papageorge, Penn vice president of facilities and real estate services.

In a separate deal, Veolia agreed to lease and maintain Penn's nine miles of steam lines, which gave it access to new customers, such as the Wistar Institute expansion under way at 36th and Spruce Streets.

Veolia Energy, which bought the Philadelphia system in 2007, is a unit of the French industrial giant Veolia Environnement. It operates 837 district steam systems worldwide, including in Trenton, Baltimore, and Boston.

The Philadelphia system, which was built by Philadelphia Electric Co. early in the last century, has gone through several owners in recent decades, but Veolia says it has the expertise and capital to stay for the long haul. "Let's face it, we had a couple of owners there that were short-term," Smedley said.

Some district heating systems have faced tough market conditions. In 2006, the Community Central Energy Corp. of Scranton abandoned service to its 26 steam-heat customers after it amassed losses and a reputation for poor service.

Veolia's predecessor, Trigen Energy, clashed with some large customers over its rates. And it has faced increasingly stiff competition from Philadelphia Gas Works, which encouraged the Four Seasons Hotel to install its own cogeneration system that produces heat and power, reducing its reliance on the steam loop.

Veolia's "green steam" initiative is an effort to retain its current Philadelphia customers, who operate 100 million square feet of buildings, the equivalent of 80 Comcast Towers.

The steam system's switch from fuel oil is the latest evolution at the Christian Street power station, which is kind of a living monument to a century of energy production.

Inside the six-story brick structure are the remnants of coal bins and long-retired boilers. Part of the building is occupied by Exelon Power's Schuylkill Station, which contains two oil-fired electrical generators that are being retired.

Veolia's latest upgrades include the installation of two new natural gas boilers to replace aging oil-fired units. Though the old boilers were primarily backup systems, they had to be operated constantly on hot standby to respond quickly, requiring a steady burn of costly fuel oil.

The two new boilers, which cost a total of $28 million, are designed to get up to speed in nine minutes, so they do not need to be operated on standby. Shutting down the old boilers allows the plant's most efficient gas-powered units to take on more load, lowering costs.

Veolia also spent $30 million to expand pipeline capacity to guarantee it will receive a steady supply of natural gas. Under the pipeline's old configuration, the plant's supplies were constrained for more than 30 days each year, forcing it to use fuel oil.

Now it will need to use No. 6 oil only on rare occasions, resulting in a major reduction in cost and emissions, which forms the thrust of its green pitch.

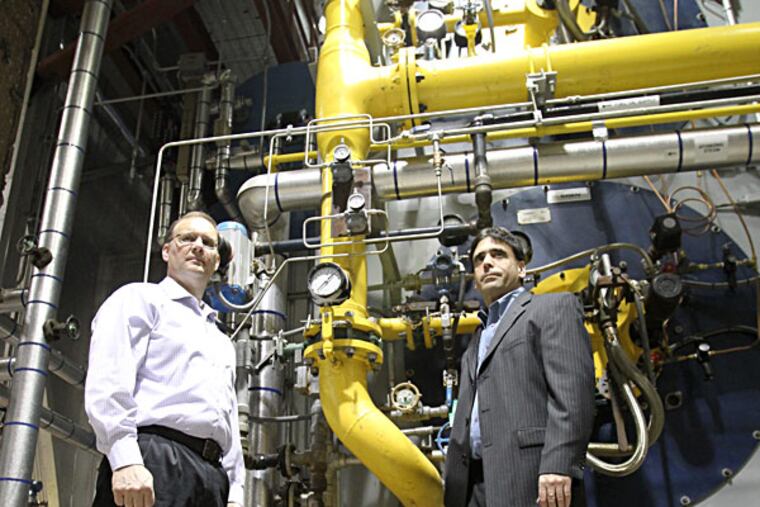

"It's a new-age approach to an old type of energy-distribution system," said Alan Ellison, the plant's director of energy and procurement.

The Steam Loop

Little-known facts about Philadelphia's steam loop:

The "loop" is actually a grid of 41 miles of underground pipe. The average pipe is 14 inches in diameter.

Most of the vapor plumes in Center City are not caused by steam leaks but come from groundwater that contacts hot steam pipes and boils off.

Veolia Energy's main steam plant at Grays Ferry is a cogeneration system that also produces 163 megawatts of electricity.

Some customers buy steam in the summer to drive their air-conditioning systems.

EndText

at 215-854-2947, amaykuth@phillynews.com, or follow @Maykuth on Twitter.