Pennsylvania may lead way in 'Clean Slate' legislation

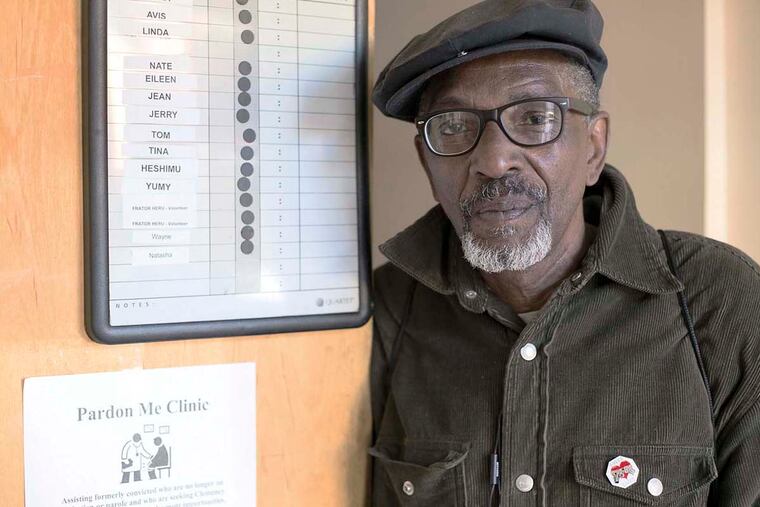

Wayne Jacobs, 66, might describe himself as a career criminal gone good, or maybe gone lucky. Once people are convicted, the individual and their families are "committed to poverty," said Jacobs, whose past includes many convictions, including one for involuntary manslaughter, and decades of in-and-out incarceration.

Wayne Jacobs, 66, might describe himself as a career criminal gone good, or maybe gone lucky.

Once people are convicted, the individual and their families are "committed to poverty," said Jacobs, whose past includes many convictions, including one for involuntary manslaughter, and decades of in-and-out incarceration.

His present?

Lobbying for big changes to the Philadelphia law governing when and how employers can use criminal records in hiring. The changes went into effect March 14. They make it easier for people with criminal records to get jobs.

"I'm proud of what I did," said Jacobs, who hasn't been in jail since 1997 and now heads a nonprofit, X-Offenders for Community Development, which lobbied for the changes.

The changes to Philadelphia's laws come at a time of increased attention to how criminal records impact employment.

In the next month or so, a bipartisan coalition of legislators in Harrisburg intends to introduce the "Clean Slate" law that "will enable Pennsylvanians with low-level, nonviolent criminal records to earn a clean slate upon rehabilitation," according to a cosponsorship memo circulated March 11.

"This legislation will implement automatic sealing of records, rather than having to file petitions one [person] at a time," said the memo, cosigned by Rep. Sheryl M. Delozier, a Republican from the Harrisburg area, and Rep. Jordan A. Harris, a Democrat whose district includes Point Breeze in Philadelphia.

"Pennsylvania has the chance to be a national model on this," said Rebecca Vallas, managing director of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.

Advocates for the changes point to the numbers: Vallas says research shows that one American in three has some type of criminal record.

And it's not only convictions that derail applicants; summary offenses, misdemeanors, and arrests without convictions can all disqualify someone from a job.

Meanwhile, management lawyers in Philadelphia are schooling clients on changes in the city code, signed into law in December by Mayor Michael Nutter.

The law expands the scope of the first "Ban the Box" ordinance passed in 2010. Employers were not allowed to ask job candidates about their criminal records on initial applications or during first interviews.

The changes in the Fair Criminal Records Screening Standards section add to it by saying employers may not consider any convictions beyond seven years.

More recent convictions can be considered, but only after a conditional offer of employment has been made.

Then, employers must weigh whether the nature and timing of the conviction would affect the job along with the applicant's rehabilitation efforts.

If the employer rejects the candidate based on criminal background, the candidate has 10 days to respond.

That's important, said Brendan Lynch, an attorney with Community Legal Services who has been advocating for the bill, because background checks often turn up errors.

If a job candidate believes an employer improperly discriminated against him, he can sue, under the changes.

That troubles management lawyer William Simmons, a partner at Littler Mendelson P.C., who sees it as opening for plaintiff's attorneys to sue, then push to grab a settlement.

Also troubling to Simmons, who held a client roundtable at his Philadelphia office Thursday, is the 10-day response.

"The employer has already gone down the path with his first candidate, and now what is he supposed to do - hold the job open while the candidate has 10 days to respond? You might lose your other candidates while you are waiting," Simmons said.

"It's pretty onerous," said John DiNome, a partner at Reed Smith, who represents employers.

"What if someone had been convicted of a murder, is released, gets a job for a moving company and goes into someone's home. Is that really what we want?" he asked

Employers can be sued, he said, for negligent hiring. Will this statute protect them from those suits? He's not sure.

Also, he said, the ordinance is confusing. It says, "Any period of incarceration shall not be included in the calculation of the seven-year period."

Does that mean, DiNome wondered, that an employer can't pass over someone who just got out of prison for a conviction that happened eight years ago?

Maybe the language isn't as clear as it could be, said Rue Landau, head of the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, the entity that will promulgate specific regulations.

But the intent is:

"What we're looking for is seven years of people being out on the street crime-free," she said. "It's an important law for Philly to give people a second chance."

For Jacobs, it's important work, particularly in his North Philadelphia community.

These changes are "going to help bring thousands of families out of poverty," he said. "I have family and friends affected by this," he said.

Two of his three sons are in prison now, due to be released this year. The third got out of prison in June.

215-854-2769 @JaneVonBergen