Prison terms sought for 4 over deadly medical tests

The former Synthes executives face sentencing for illegally marketing a bone cement to surgeons. Three people died.

(This article was first published June 5, 2011.)

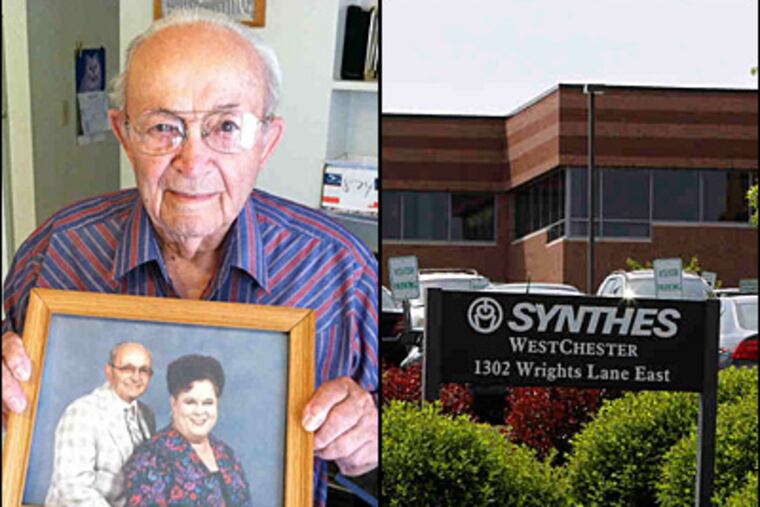

ANTLERS, Okla. - Love, for Ike Eskind, meant working for free alongside his wife, Lois, on her graveyard shift at a convenience store. He lifted boxes to save Lois from excruciating pain in her back.

Later, love meant telling his wife that it was OK to quit that job, that his railroad pension could keep the lights on in their trailer outside this little town in southeastern Oklahoma.

But the simple bliss of seniors Ike and Lois Eskind ended Jan. 13, 2003. About 140 miles from home, Lois lay down on an operating table at the Texas Back Institute in the Dallas suburb of Plano, hoping a spine surgeon could provide relief by injecting bone cement into two vertebrae crumbling from osteoporosis.

She never got up from the table.

"I sure do," Ike said when asked about missing Lois. "She was always smiling."

Eskind was the first of three patients to die during what prosecutors later called an illegal clinical trial of a bone cement promoted by Synthes Inc., the medical device maker near West Chester, Pa., and its wholly owned subsidiary Norian Inc. between May 2002 and fall 2004.

Pharmaceutical executives rarely get jail time for corporate crimes, but federal prosecutors in Philadelphia this week will argue for sentencing guidelines that could mean up to a year in prison for four former Synthes executives in connection with the illegal testing and marketing of Norian bone cement.

Synthes (pronounced SIN-theez) and Norian hoped to profit from the spinal surgery market created by millions of older Americans with back pain. Lois Eskind was 70. The other two patients to die in this illegal test marketing were an 83-year-old man and an 83-year-old woman, both from Northern California.

Court documents show that former Synthes board member and spine surgeon Ken Lambert referred to the trials in e-mails to company leaders as "human experimentation whose only defense seems to be that it will be a small study."

Lambert was soon fired.

"This is an egregious case, and it made us firm in our belief that we should draw a line here," Greg Demske of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Inspector General said in October when the companies pleaded guilty.

Eskind, like the other patients who died, had plenty of other health problems, and no one can say for sure that the Norian bone cement caused their deaths.

By the time Eskind died, thousands of patients nationwide had thought they had been helped by such surgery, called vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty, performed by several types of doctors, including many in Philadelphia.

Using general or local anesthesia, doctors put a needle and a tube into a vertebra and fill cavities left by osteoporosis or other damage with cement. But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had approved no cements for such use until April 2004 - two years after Synthes had begun its illegal clinical trial of Norian cement. The FDA approval for Norian's cement did not include use in this procedure.

Legally, doctors can use whatever drugs and devices they want, and doctors were using bone cements for spine surgery "off-label," meaning without FDA approval. It is illegal, however, for a manufacturer to promote a drug or surgical product for use in a manner unapproved by the FDA.

And that's what Synthes did, according to prosecutors.

Synthes pleaded guilty to one misdemeanor count of introducing adulterated and misbranded bone cements into interstate commerce. Norian pleaded guilty to one felony count of conspiracy and 110 misdemeanor counts for shipping adulterated and misbranded cement. Michel Orsinger, an executive of Synthes and Norian, signed the settlement agreement for each company.

The companies' fines totaled $23.7 million, including a portion related to 31 fraudulent Medicare claims. Synthes divested Norian to comply with the plea, selling the assets May 24 to Kensey Nash Inc., of Exton, for $22 million. Earlier, in late April, Johnson & Johnson agreed to buy Synthes for $21.3 billion.

The four now-former Synthes executives pleaded guilty in 2009 to one misdemeanor count each for their parts in the scheme to market Norian for the off-label use on spines in their roles as corporate officers with the responsibility to prevent such violations.

The executives are:

Michael D. Huggins of West Chester, who was president of Synthes North America and later president of Synthes Spine, both divisions of the company. Messages left at Huggins' home were not returned, and one of his attorneys, Katherine Recker, declined comment.

Thomas B. Higgins of Berwyn, who was president of Synthes Spine, reporting to Huggins, and later became senior vice president of global strategy for Synthes. Higgins declined to comment, as did one of his attorneys, Adam Hoffinger.

Richard E. Bohner of Malvern, who was Synthes' vice president of operations. A message left at Bohner's home was returned by one of his attorneys, Brent Gurney, who declined to comment.

John J. Walsh of Coatesville, who was director of regulatory and clinical affairs and reported first to Bohner and later to Huggins. Walsh, who joined Synthes in 2003, declined to comment.

On Monday, they are scheduled to appear in federal court in Philadelphia for perhaps a week of hearings on sentencing guidelines. Judge Legrome D. Davis will eventually sentence the four. Prosecutors and defense lawyers declined to comment on their sentencing hopes. But court filings indicate that defense lawyers likely will argue for no prison and little probation, besides a $100,000 fine each man has to pay. Prosecutors appeared ready to argue for the maximum one year in prison, and they have fought for most of two years to have evidence discussed before sentencing, knowing how rare it is for pharmaceutical executives to go to jail.

"In regards to the four executives in the Synthes case, it was clear they knew about certain issues with regards to patients," said Zane Memeger, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, after a recent meeting on health-care fraud. "Despite that knowledge, they continued to experiment with the product in an improper fashion."

In recent years, the U.S. Attorney's Office in Philadelphia has prosecuted major pharmaceutical companies, resulting in big financial settlements with Cephalon ($425 million in 2008), Eli Lilly ($1.4 billion in 2009), AstraZeneca ($520 million in 2010), and Novartis ($422.5 million in 2010).

Those dollars, however, are small change compared with companies' potential profits. Johnson & Johnson chairman Bill Weldon justified the Synthes purchase to Wall Street analysts by noting that orthopedics was a $37 billion market. Much of that money comes from tax dollars, via Medicare and Medicaid, which are administered by the Department of Health and Human Services.

"We are concerned that the providers that engage in health-care fraud may consider civil penalties and criminal fines a cost of doing business," Lewis Morris, chief counsel in the HHS Office of Inspector General, testified this year to the House Ways and Means subcommittee on oversight. "As long as the profit from fraud outweighs those costs, abusive corporate behavior is likely to continue."

Charles Elson of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware said sending corporate leaders to prison would change the equation.

"Jail time is much more of a deterrent than fines," Elson said. "Liberty is much more precious."

Synthes' chief executive officer and largest shareholder, Hansjorg Wyss, 73, was not charged in the criminal case, though the government said in the indictment that he had "directed" in 2001 that the test market begin. Memeger declined to say why Wyss was not charged.

Wyss declined to comment when reached at home on the night of the Norian sale, and his office and a company spokeswoman did not answer subsequent interview requests.

Wyss dismissed Lambert when Lambert spoke up about the bone-cement problems. In an interview, Lambert joked that he should have sued as an official whistle-blower, which can mean a financial reward. There was no official whistle-blower in this case.

"I thought, 'If I'm ever going to stand up to something, this is my test,' " he said. "You just know it's right. You wonder how they could have done what they did. I guess their eyes get used to the dark after a while. How do they make that decision? I have no answer for that."

Plan of action

The indictment, pleadings - signed by company lawyers and the four executives - and thousands of pages of court documents, including many internal Synthes memos and e-mails between employees, make clear that Synthes had a plan from 2000 onward to encourage key surgeons to test its Norian bone cement in spinal procedures not approved by the FDA.

Some of the e-mail evidence shows that company executives knew their test-market plans were illegal and were trying to avoid having employees go too far, too fast in pushing products to surgeons, lest the plan be exposed.

In one example, Huggins sent an e-mail on May 30, 2002, to five employees, including Higgins and Bohner, that said, in part, "We shouldn't be sending out product without proper protocols, surgeon sponsors, etc. As you know, we have gone through great lengths in SUSA [Synthes USA] to train surgeons on Norian's use. It seems Spine is bypassing the needed blocking and tackling without thinking this all the way through. In addition, I had a long phone conversation with Dr. Lambert who is very concerned about the Spine plan. I am now having second thoughts. Please make [sic] that shipments are stopped until we can discuss and resolve all the issues."

But the test marketing didn't stop, even though Synthes already had evidence that Norian bone cement might cause fatal blood clots.

A Los Angeles surgeon was one of the first to use the Norian SRS cement in vertebroplasty. He had two "adverse events" on the same day, Feb. 26, 2001, with both patients experiencing a sudden drop in blood pressure. Neither died, but one spent several days in the intensive care unit. Synthes filed adverse-event reports with the FDA. Bohner got an e-mail about it March 16, 2001. A few weeks later, that surgeon attended a Synthes-organized seminar led by Higgins.

Bart Sachs, then of the Texas Back Institute, was one of the surgeons involved in the test marketing and he operated on Lois Eskind. Sachs said he was paid by Synthes.

Did Sachs tell Eskind's husband that he was trying something new with the surgery?

"Not that I remember," Ike Eskind said.

How about her daughter, Eva Sloan?

"No," Sloan told The Inquirer.

Did Sachs tell Eskind that he was testing something new on her?

"I wasn't testing anything," said Sachs, who now lives and practices near Charleston, S.C. "I didn't tell her, because I wasn't testing and I wasn't experimenting."

Husband, daughter, and surgeon all agree that Eskind was a surgical risk because she smoked until six months before the surgery, had heart disease and prior back operations. Synthes documents submitted as evidence in the case say she signed a form attesting to her high risk.

Sachs said that he had used Norian's bone cement previously for other kinds of surgery, that he thought it might be superior to alternatives, and that he had said so to Lois Eskind. Other evidence suggests he was new to the use of Norian in spinal surgery.

Lambert, the former spine surgeon and Synthes board member, would dismiss Sachs' distinction between what's experimentation and what's not.

"I'm a doctor, and it offended me," Lambert, in the interview, said of the company's test market.

What happened?

"They aren't bad men, but why do good people do bad things? It's the corporate culture, really," Lambert said. "They did things they shouldn't have done and they were not alone. There are some bad people who got away with stuff. I have a lawyer friend, who refers to people like that as non-people, non-breathers. They are loyal to the corporation, not to people. The government should crack down.

"This affected the world of orthopedic implants. Some good could come out of it, but you hate to have it happen. They gave into that corporate culture. I have no answers for why."

Synthes buys Norian

The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates 10 million Americans have the disorder, in which bones become brittle, leading to frequent fractures, stooped posture, and pain. The foundation estimated that in 2005, just after the Synthes illegal test marketing effort, osteoporosis-related fractures were responsible for $19 billion in medical costs.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2009 said the procedure gave no better results than a placebo, and questioned whether it was worth the risk or cost. But in 2000-01, there had been no thorough clinical studies, and the procedure was popular in the surgical spinal community. Synthes wanted to profit from that market.

Norian, which was based in Cupertino, Calif., made a bone cement for use in fractures of the skull, arms, and legs. In 1999, Synthes bought Norian and looked for other fractures to fix. With the aging population in mind, Synthes focused on spinal surgery. Bone cement is considered a device, rather than a drug, when it comes to FDA approval.

"I had used the bone cement for other parts of the body and it worked well," said Lambert. "But I told [CEO Wyss] that it was not like putting in plates and screws. This is more like a drug than putting in plates and screws. But there was so much money in vertebroplasty that the corporate people gave into it. They chose to make a corporate decision rather than a decision for people."

Synthes was formed in the 1950s by four Swiss surgeons, so there is history and logic in its trying to appeal to that group, since doctors have great freedom to choose their tools. Synthes had competitors, including Kyphon, Malvern's Orthovita, Stryker (which bought Orthovita in May) and Johnson & Johnson's own DePuy.

Norian's XR bone cement, a successor to Norian SRS, received FDA approval on Dec. 19, 2002, with a label saying it could be used for filling bony voids that were "not intrinsic to the stability of the bony structure" in the arms, legs, skull, and pelvis. The FDA also required the label to say XR was "not intended for treatment of vertebral compression fractures," words that did not appear on competitor product labels.

Part of the concern was the mixing of the bone cement and the tendency for calcium phosphate in it to clot with blood. When clots reach the heart and lungs, blood pressure can drop to dangerous levels. And near the spine is a major vein that carries blood back to the heart from the lower body.

Fearing it was already behind the competition, prosecutors said, Synthes skipped three years and the $1 million cost of clinical trials. Instead, it took the dual track of urging the FDA to remove the restriction on the label while running the secret trials. In the process, court filings suggest, Synthes would collect useful data, and surgeons would say and write good things to build a case for removing the FDA warning.

Synthes paid for surgeons to meet in San Diego and Charlotte, N.C., to hear discussions and observe demonstrations on cadavers. Surgeons were told they could not reorder supplies unless they returned forms explaining what had occurred in the operations. About 200 operations occurred during the test market.

But then Lois Eskind died.

'Family life was good'

When she died, Lois Eskind left behind, among others, grandchildren and great-grandchildren who called her "Granny." "She thought they were everything in the world," said Ike, her second husband. Eskind's first husband worked in construction, so the family (including a son) moved around Oklahoma as the father sought employment.

"My family life was good," said her daughter, Eva Sloan. "My dad worked hard, and my mother was a powerful personality and a strong person and a good mother."

Sloan's parents divorced, and her father died before her mother. Ike and Lois married in 1990. Ike's railroad pension and Medicare paid her medical bills, including that last operation.

Lois Eskind had been to pain management clinics before she and Sloan learned of the Texas Back Institute.

"I read about bone cement. I think it was on their website," Sloan said, adding that she thought the use of the bone cement was routine. "We went for an appointment with Dr. Sachs. We talked about her heart problems. He said he could not guarantee that she would make it through. She was considered more of a riskier candidate than some others."

Why did she go through with it?

"She was in so much pain," her husband said.

When Eskind was wheeled into the operating room for the last time, a Synthes sales representative named Patrick Burgess was also there, according to a confidential Synthes memo obtained by prosecutors and entered as evidence in the case. Burgess could not be reached for comment.

Patients familiar with signs in doctors' offices saying drug sales representatives are unwelcome on particular days of the week might be surprised to hear that a sales rep was in the operating room helping to mix a potion going into someone's body, but Sachs and others said that was normal.

Regardless of who is in the room, FDA law requires device manufacturers to notify the agency within 30 days of receiving any information about an adverse event involving one of its devices, but Synthes did not report Eskind's death to the FDA.

Synthes employees talked about the event internally. Burgess and Sachs spoke with three Synthes employees. Handwritten notes by those employees, from the conference call with Sachs three days after Eskind's death, were entered as evidence in the criminal case. All three sets of notes report a discrepancy between Burgess' description of Sachs' technique and Sachs' view of events when he was trying to inject the bone cement into the second of two fractured vertebrae.

Within 15 seconds of the second cement injection, according to Synthes memos, Eskind's blood pressure dropped and her heart stopped. The injection site was sutured, and she was flipped over on her back. Sachs and three anesthesiologists tried for 30 minutes to resuscitate her but failed.

Stuart Weikel, one of three employees on the conference call with Sachs, wrote in his notes: "Sachs doesn't know what caused it. He is concerned about the Synthes technique b/c this is only his 2nd case with a technique that hasn't been widely used. He did the technique the way he was supposed to and the outcome was catastrophic. Dr. Sachs says he's not condemning the technique. This has never happened to him before, though, and so he's concerned. Says a patient this compromised he would be more comfortable with a different system. Going forward, more caution is required and patient selection is critical."

Whatever his concern, Sachs didn't say much to Sloan when he emerged from the operating room to tell her that her mother was dead.

"He just said that she passed away and didn't make it," Sloan said. "Beyond that, well, I just shut down. You're in shock."

Until the recent discussion with an Inquirer reporter, Sloan said, she assumed her mother had died of a heart attack. And she might have. Eskind was cremated, as was her wish, without an autopsy, and an autopsy might not have assigned blame to the bone cement. Big drops in blood pressure also occurred in connection with the other two deaths. But in the autopsy after the third death, the pathologist wrote that the foreign matter found in the veins of the lungs might have been lodged there by the CPR used to try to revive her.

Proper clinical trials are supposed to help sort out such things. Synthes didn't stop, though. Later in 2003, Walsh helped put together an updated training guide, which used Eskind's X-rays as teaching materials.

"I know I didn't realize it was experimental," Sloan said, though she knew of the possible fatal outcome. "She had known this was a possibility, and I guess we assumed it was her heart. But if this could have been caused by a clot, then, well, that's kind of shocking."

Contact staff writer David Sell at 215-854-4506 or dsell@phillynews.com.