Prison inmates learn credit, banking, and personal finance to ease reentry into the world of money

Many inmates at the Department of Correction's SCI Chester have never opened a bank account, instead storing their cash in a safe or under the mattress.

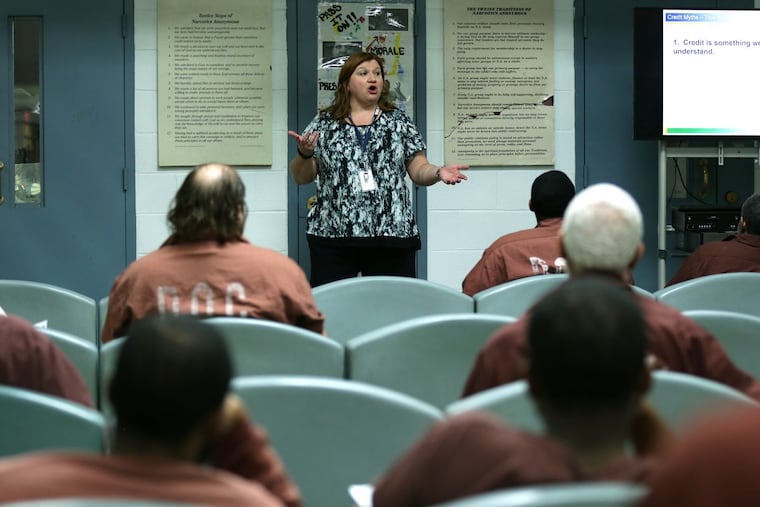

Becky MacDicken loves to educate Pennyslvanians on personal finance, credit reports and scores, and her audience embraces her classes — especially the inmates at the Department of Corrections' SCI Chester prison, many of whom have never opened a bank account, instead storing their cash savings in a safe or under the mattress.

An outreach specialist with the Pennsylvania Department of Banking and Securities, she has visited every prison or correctional facility in the commonwealth at least once in the last year. Her work stems from the Department of Corrections' formal partnership with the Department of Banking and Securities to teach workshops on budgeting, predatory loans, and other topics to people in the corrections system.

"I encourage inmates to begin their financial education before they get out of prison," she said while setting up for her workshop in a noisy cell block.

At SCI Chester prison, soon-to-be-released inmates are hungry for knowledge — roughly 35 inmates, or half the unit, sit patiently and listen intently during the two-hour session. Some are senior citizens, receive disability or benefits, and own property or other assets in the outside world. Others are in their early 20s and want to start fresh financially and in life.

"I know nothing about banking, savings, or retirement," said Andre, an inmate in what's known as the Transitional Housing Unit of SCI Chester, a stone's throw from Harrah's casino and the industrial highway alongside I-95. Last names of inmates and their ages are withheld. Andre has already completed the FDIC Money Smart curriculum, 12 modules in all, and "I'd like to go to community college when I get out, maybe start a carpentry and construction business. This stuff is all new to me. I dealt in cash only, I ate out every night, paid cash for clothes, cellphone, my rent. I even paid cash for my car, which I bought at an auction. My mom had a bank account and credit cards, but I didn't."

Since this prison unit posts high turnover, with 60 or so prisoners rotating out every few months, MacDicken is called back routinely for financial-education workshops. The prison's general population tops 1,600 or more inmates at any one time, according to Louisa Perez, superintendent's assistant for SCI Chester.

Today's class: What is a credit score and how to access credit to start a business, get a loan, or refinance existing debt.

"Is CreditKarma.com better than the annual credit report you can get for free?" asks one man in the audience during her PowerPoint presentation.

"Great question," MacDicken answers. "I'll get to that after we talk about what are the components of a credit report vs. a credit score. But the most important thing is, try to order copies of your credit report before you get out of here."

Another inmate, Rolando, may want a line of credit "to open a barbershop or tattoo parlor. I don't know anything about credit, I never had a bank account or a credit card." Before prison, Rolando banked most of his money using prepaid debit cards and added value using cash.

In the gray cell block, two stories high with black painted numbers, inmates sat in similarly gray plastic chairs perusing MacDicken's handouts: a paper copy of a form to request one's credit report (free on annualcreditreport.com, but inmates don't always have access to the internet or a computer) and information about the Pennsylvania Department of Banking and Securities.

"We regulate state-chartered banks, the credit unions, and the check-cashing companies. I'm here to give you some knowledge about them," she told the crowd, echoing in the concrete hall.

Finance tips from prison

If you don't have credit, a great way to start building it is establishing a regular payment history so lenders see you are creditworthy and will pay your debts.

One option: Open a prepaid bank account with a credit line that you pay for up-front.

"Go to a bank and ask for a secured credit card that has collateral, say, starting with $500 or $1,000," MacDicken recommends. Pay the bill every month on time and establish a payment history, and do the same with a cellphone and other utility bills, if you can.

Do you owe court fines or restitution? That can affect your credit — even something as minor as a library book late fee or parking ticket or as major as medical debt shows up on your credit.

"Medical debt is the number-one reason for bankruptcy in America," MacDicken said. "It really hurts a lot of people's credit scores. If you can establish a payment plan, even $5 a week, and negotiate down the debt with the hospital or doctor, they'll take the payment. They know it's better than discharging that debt in bankruptcy."

Behind on student loans? Contact your lender or the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (www.pheaa.org) and ask for help. If you're in default and your lender won't budge, file a complaint with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a federal agency that can intervene on your behalf (www.consumerfinance.gov) and refer you to a local, nonprofit credit counselor. Don't fall for those ads on television promoting student-loan consolidators; you can solve your issues for free.

"If you want a business loan when you get out, make sure to pay down or address personal debts first," she told the audience.

Finally, prison inmates are definite targets for identity theft, MacDicken said.

"I've given workshops with juvenile lifers who checked their credit, only to find out an uncle had gotten a loan in their name." Check with all three credit bureaus to find out whether anyone has opened an account in your name — whether you're in jail or not.