Philadelphia releases three-year plan to improve street safety

The city's roadmap to improve street safety in Philadelphia, released Thursday, included specific priorities - among a list of more than 100 action items - designed to make the city streets safer.

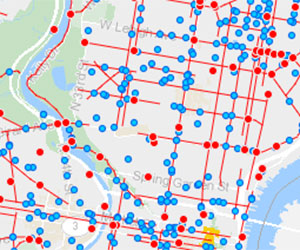

Within a 44-page report on street safety in Philadelphia released Thursday is a map showing the most dangerous streets in the city.

On that map, red lines trace roads like a cross hatch of scars, including Market Street, Broad Street, and Roosevelt Boulevard. The map highlights only about 12 percent of all the paved roads in the city, but they account for 50 percent of the serious injuries and deaths that happen in Philadelphia. In the fight to make the city's streets safer, those red lines are where the battle will be fought.

The Most Dangerous Streets

in Philadelphia

On Thursday, Mayor Kenney unveiled the Vision Zero Three-Year Action Plan, which details steps the city can take over the next three years to make streets safer, with the long-term goal of eliminating traffic-related deaths entirely by 2030. It's a target that's easy to get behind.

"Looking at the core principles, you're talking about making it safer for everybody," said Councilman-at-large William Greenlee. "Obviously we're all for that."

It's the details that could prove divisive. During a news conference Thursday, Mike Carroll, the city's deputy managing director for transportation and infrastructure systems, made clear that safety comes with a cost.

"Some streets are going to be slower," he said. "Driving around is going to take a little more time."

Reducing speed is a major focus of Vision Zero's approach. The report notes that the faster a car is going when it strikes a person, the worse that person's injuries are. Encouraging biking and walking is another priority. Fewer cars can mean fewer crashes, and meanwhile, the city's population gets healthier, and the air gets cleaner, officials said.

The report proposed more than 100 action items covering engineering, enforcement, education, data analysis, and policy, and included time frames for each recommendation. The action items include protected bike lanes, altered intersections, creating neighborhood slow zones, and managing loading zones differently.

The report hewed closely to a draft issued in March, with many of the same priorities listed. But the newest iteration of the report still doesn't include specific proposals for specific streets. At Thursday's news conference, Kelley Yemen, the city's complete streets director, said that some work was already underway but that specifics on future projects would come out in about six months.

Some recommendations in the report, which was assembled by a task force of city and state officials and community advocates, require significant changes to street architecture, ranging from installing bike lanes to altering intersections and lane widths. Many of those projects require the approval of Council, and city legislators know how contentious street changes can be. About a month ago, a protected bike lane opened on Chestnut Street between 45th and 34th Streets, in Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell's Third District. Residents are furious over the lost vehicle lane, she said.

"All I do is get complaints every day about the lack of traffic access on Chestnut," she said Thursday.

Greenlee encountered similar fury in 2014 from neighbors on a two-block stretch of 22nd Street, where the city proposed adding a bike lane that would have narrowed travel space for vehicles. He agreed with their complaints, and the proposal died.

One of the Vision Zero report's recommendations would give the city engineer more autonomy to make street changes. Council members aren't keen on the idea.

"I am not comfortable having somebody who sits in the room who doesn't necessarily live in my district make decisions for me," Blackwell said.

No council members attended Thursday's news conference. City officials and council staff later said their absence was due to the news conference being scheduled during on a Thursday morning, when council was occupied with caucus meetings.

Rules that require Council approval before making some streetscape changes, though, are likely to hinder the city's ability to implement the Vision Zero recommendations, said Jon Geeting, an urbanist activist in Philadelphia.

"I think that's probably the biggest obstacle to success to this plan," he said. "There's no obvious pathway in the document to how it will be that council members will come to agree to any of this stuff."

One member of Council, Councilman-at-large David Oh, questioned whether slowing cars down was even the best approach.

"I think just slowing down traffic to slow it down, you increase idling, you increase the opportunities for accidents, you increase road rage," he said.

Mayor Kenney said, though, that conversations with Council can convince members of the effectiveness of Vision Zero's approach.

"You don't govern by putting pressure on people," he said. "You govern by convincing them of your position."

The report lists six safety violations most likely to cause injuries and death — reckless and careless driving, running red lights and stop signs, driving while intoxicated, failing to yield, illegal parking, and distracted driving — and recommended that enforcement efforts focus there. The report also recommends creating a centralized database for crash information and another database to track streets and intersections with line-of-sight issues.

The report recommends speed cameras to complement red-light cameras on Roosevelt Boulevard.

City money includes $1 million for Vision Zero safety measures for the Streets Department and $500,000 to the Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems from Philadelphia's operating budget.

The report cites some sobering statistics to explain the need for Vision Zero: Four children a day are involved in traffic crashes, and 100 people are killed every year. An additional 250 are severely injured.