'Talk about an unholy alliance': Lawyers, doctors and pharmacies

Big workers' compensation law firm Pond Lehocky and Philadelphia-area pain doctors make money by steering injured workers to mail-order pharmacies that they own.

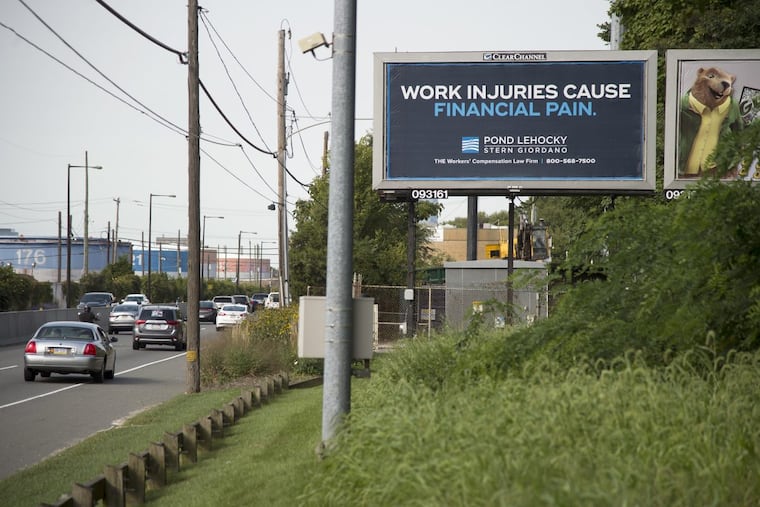

Pond Lehocky is the biggest player in town for workers' compensation cases, targeting employees who get hurt on the job with TV ads and billboards that seem to loom on every stretch of Philadelphia's highways.

"There are many law firms in Pennsylvania," goes one of the firm's TV spots, "but no one works harder for you — no one. They'll do more to get more for you."

Pond Lehocky's top lawyers have also been doing more to get more for themselves, according to an Inquirer and Daily News investigation.

Three partners at the firm and its chief financial officer are majority owners of a mail-order pharmacy in the Philadelphia suburbs that has teamed up with a secretive network of doctors that prescribes unproven and exorbitantly priced pain creams to injured workers — some creams costing more than $4,000 per tube.

Pond Lehocky sends clients to preferred doctors and asks them to send those new patients to the law firm's pharmacy, Workers First. The pharmacy then charges employers or their insurance companies for the workers' pain medicine, sometimes at sky-high prices, records show.

An email to doctors, signed by one of the law firm's founding partners, Sam Pond, outlined the arrangement: "For all patients that you may see with a workers' compensation claim, referred to you from our office or elsewhere, we ask that you have our pharmacy, Workers First Pharmacy Services, fill the scripts."

Some of the doctors sending patients to Workers First also own a piece of the pharmacy, enabling them to make money from both patient care and the prescriptions.

Pond Lehocky received state approval to open its pharmacy in October 2016. The application stated that no medical practitioners had a proprietary interest in the pharmacy. But, in fact, several doctors are part-owners, the Inquirer and Daily News have learned.

It operates on Lancaster Avenue in Haverford, behind a windowless door with a peephole and a small, taped-up paper sign that reads "Workers First."

Pond said Workers First Pharmacy follows all state ethics rules while quickly getting medications to injured clients even when employers and their insurance agencies refuse or are slow to approve treatment. "This is just an add-on service," Pond said in a recent interview. "I'm very passionate about the human suffering."

Legal and medical ethicists say breaking down the walls among lawyers, doctors, and pharmacists can lead to conflicts of interest and create a financial incentive to prescribe the costliest drugs — whether or not they are medically appropriate — or to prolong workers' comp legal disputes to boost revenues.

"Talk about an unholy alliance," said Joseph Paduda, president of CompPharma, a trade association for workers' comp pharmacy-benefit managers.

These sorts of doctor- and lawyer-owned pharmacies are largely unknown outside of the local workers' comp industry and are not fully understood even within legal and medical communities, because the lawyers and physicians behind them have kept a low profile or sought to conceal their ownership.

"This is new to me," said Dr. Steven Joffe, chief of the division of medical ethics at the University of Pennsylvania's medical school. "I can't speak to what's going on in any individual case, but the whole setup seems ripe for corruption."

‘Let us handle the fine print’

In Pennsylvania's workers' comp system, medical bills for injured workers are typically covered by employers or employers' workers' comp insurance providers.

Doctors here previously exploited a loophole in the system by bypassing pharmacies and dispensing narcotic pain medications and other prescription drugs directly to patients at costs typically three to 10 times the amount charged by a retail drugstore.

In 2014, state lawmakers enacted legislation that cracked down on physician drug dispensing. State Rep. Ryan Mackenzie (R., Lehigh), a cosponsor of the bill, said physician-owned pharmacies seem to be a similar attempt to boost revenue.

"Since you can't do it directly from your office, they set up these pharmacies that are separate entities but obviously related," Mackenzie said.

In October, Pond Lehocky got in the game with its own pharmacy, putting a new twist on the business model.

"It appears what's happening is, the attorneys looked at mail-order pharmacies and said, 'Heck, we can capture all that profit ourselves' with this sort of parasitic relationship with the attorneys referring patients to specific doctors," Paduda said.

On its website, Pond Lehocky is vague about its relationship to Workers First, saying it is "partnering" with the pharmacy to help clients get the best pharmaceutical care.

Clients who click through to the pharmacy's website are told: "Focus on your recovery. Let us handle the fine print."

That's what Francis Elliot did when his doctor told him he needed medication carried by Workers First.

Elliot, 51, a former Philadelphia Parking Authority enforcement officer from Fox Chase, has been on workers' comp for about seven years. He went to Pond Lehocky after falling on the job and sustaining a herniated disc, which led to several other medical ailments. His photo appears on some of the law firm's billboards.

"I would be dead and not sitting here right now if it wasn't for Pond Lehocky," Elliot says in a testimonial video on the firm's website.

This spring, Elliot said, he was seeking a new doctor and his lawyer at Pond Lehocky directed him to Relievus, a network of pain-management clinics. Elliot chose a Relievus doctor, Uplekh Purewal, who wrote him a script for topical diclofenac solution, an anti-inflammatory. Elliot said Purewal sent the script directly to Workers First.

The new medicine seemed to work at first, Elliot said, but now it doesn't do anything.

"You get relaxed," he said. "But it doesn't last long."

Records show that Workers First has charged more than $1,600 for a 5-ounce bottle of diclofenac. It's a relatively inexpensive topical solution that can be purchased wholesale for $60 to $70, pharmacists said.

Elliot, after doing some research and learning from a reporter that doctors co-own the pharmacy, is concerned that he's been drawn into a moneymaking scheme. He said he didn't know that Pond Lehocky owned the pharmacy — or that doctors were getting a cut.

"I don't want to be a part of something unethical," Elliot said. "I don't know what's going on."

The Relievus medical network includes Dr. Rishin Patel, CEO of Insight Medical Partners, and Dr. Miteswar Purewal, founding partner of Insight and Uplekh Purewal's brother. Insight, a Conshohocken company that manages workers' comp pharmacies, owns a percentage of Workers First.

Workers First has also charged more than $1,900 for 6 ounces of lidocaine 5 percent ointment. A 1-ounce tube of the same medication can be purchased online for about $14.

Phil Walls, chief clinical officer at the pharmacy-benefit management company myMatrixx, said those prices are "grossly inflated."

"As a pharmacist, it's perpetually embarrassing to me to see what some of my colleagues will do to take advantage of the system," Walls said. "The fact that they charge these outrageous amounts is just horrible."

Workers First has charged at least $4,300 for its compounded pain creams, in which medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in cream form are typically mixed with muscle relaxers and other medications meant to be taken orally. The law firm didn't respond to questions about specific costs but said in a statement, "We are comfortable making profits instead of big pharma."

Expensive compounded pain creams have played a role in several high-profile criminal cases, including a $28 million prescription-drug-fraud conspiracy that involved New Jersey public employees and medical fraud charges against reputed Philadelphia mob boss Joey Merlino.

Last year, federal prosecutors who broke up a $175 million prescription-cream scam in Florida said coconspirators were raking in as much as $31,000 per tube from insurance companies.

Dr. Steven Stanos, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, said it's unclear if these compounded creams work, if they're safe, or how much, if any, oral medication is absorbed through the skin.

"They're charging exorbitant amounts of money for a cream, and it's not based on good evidence," Stanos said.

Jane Lombard, who chairs the workers' compensation group at Swartz Campbell and represents employers and insurance firms that pay medical bills for injured workers, said the cost of some of the creams "shocks the conscience."

Speaking in general and not about any specific case, she said: "Back injuries did not get so much worse in the past couple years that we need $4,000 creams. It's because there are these ownership interests in pharmacies."

Lombard said trying to find out who owns the obscure pharmacies in the Philadelphia area is "exceedingly difficult" because owners put up legal roadblocks. Workers' comp judges who handle fee disputes also have limited subpoena power to uncover conflicts.

"It used to be the attorneys and doctors would get their fee for the office visit and service," Lombard said. "But with this untapped font of dollars it's, 'Let's prescribe everyone four things on the first visit — maybe a cream, an opioid, cyclobenzaprine, and, hey, let's try another muscle relaxer.' "

Opinions vary on ethics

Sam Pond, a tough-talking Torresdale native who's influential in Democratic political circles, said his law firm started Workers First Pharmacy to stand up to "diabolical people" at insurance firms who frequently deny medication to his clients to boost their own profits. A former amateur boxer, Pond describes it as a David-and-Goliath scenario.

"You ever have an insurance claim? You ever go up against these bastards?" Pond asked.

He said Pond Lehocky advises clients to use Workers First because they will receive their medication while a medical claim is being disputed. The firm tells clients it has a financial interest in the pharmacy, and most of them are still using other pharmacies, he said.

Pond said he has no control over doctors, which pharmacies they use, or what drugs they prescribe.

"I couldn't even pronounce half the scripts," he said.

Pond said the letter he sent doctors — which twice asks them to use Workers First for their workers' comp patients — does not constitute a quid pro quo. He said he did not believe doctors might feel pressured to use his pharmacy to continue receiving patient referrals from Pond Lehocky, a major pipeline for new patients.

"I would be outraged — outraged — if I heard that," Pond said.

While Pond insists the firm is on solid ethical footing, Joseph Huttemann, a partner at rival workers' comp law firm Martin Law, said attorney-owned pharmacies appear to violate the state rules of professional conduct that prohibit an attorney from acquiring a proprietary interest in the subject matter of the litigation, aside from an attorney's fee.

"We take the position that we're not going to profit off the potential abuse in the system on the medical end of clients," said Huttemann, former chairman of the workers' comp section of the Pennsylvania Association of Justice, the trial lawyers association.

W. Bourne Ruthrauff, cochair of the Philadelphia Bar Association's committee on professional responsibility, said he hadn't heard of attorney-owned pharmacies. But, he said, employers could use the pharmacies to contest the necessity of expensive medications, to the detriment of the client.

"If it became known that a particular pharmacy and lawyer is doing this, it seems to me that defense counsel would use that to call into question the legitimacy of the expenses," Ruthrauff said. "It makes it look a little like a scam."

Geoffrey Hazard, a nationally recognized legal ethicist and professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, said it could lead to exploitation and kickbacks.

"It creates an incentive for the principal professional to select somebody who will give him a breakoff," Hazard said.

Daniel J. Siegel, a Havertown lawyer who represents Workers First and physician-owned pharmacies in the area, said ethics lawyers are divided on the issue.

Siegel, co-vice chairman of the Pennsylvania Bar Association's ethics committee, said, "Clearly there is a potential for a conflict." But he believes such a conflict can typically be waived by the client under the state's professional conduct rules. He said an attorney can obtain the waiver orally or in writing.

Abraham Reich, a Fox Rothschild attorney whom Pond Lehocky consulted for an ethics opinion on opening a pharmacy, said the firm does not run afoul of professional conduct rules with Workers First. He said the arrangement is similar to a contingency-fee agreement in which a lawyer gets paid if the client does.

"The interests are aligned," Reich said. "They're both trying to recover the most amount of money."

Not something to talk about

In Harrisburg, Mackenzie has sponsored a hotly debated bill that would create a preapproved drug formulary for workers' compensation cases. He says that by introducing evidence-based guidelines for treating injured workers, the bill would cut off payments for overpriced, unproven pain creams and other medications as well as reduce the overprescription of opioids — a major problem in Pennsylvania.

"There is no way to fix this. This bill is bad to the bone," Dr. Gene Levinstein wrote in a May op-ed for City & State PA. "Doctors will be required to use a preapproved formula to determine which drugs would be eligible to be used to treat patients. However, we have no idea who would be responsible for deciding which drugs would be approved as part of the formula."

Pond Lehocky cites Levinstein's op-ed on its website, and one of the law firm's advocacy groups has circulated it on social media to help fight Mackenzie's House Bill 18.

None of them disclosed that Levinstein owns part of Workers First. Levinstein did not reply to repeated calls seeking comment.

According to Workers First's Board of Pharmacy application, 65 percent of the pharmacy is owned by Sam Pond; law partners Jerry Lehocky and David Stern; and law firm CFO Bryan Reilly.

Pond Lehocky told the Inquirer and Daily News that Levinstein and at least six other doctors are among the other owners of the remaining 35 percent.

One of the doctors, Gerald Dworkin, has sent patient scripts to Workers First, records show. In a July workers' comp deposition, he said he owned 3 percent of the pharmacy. "It's not something I'm supposed to be talking about," said Dworkin, chairman of the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

He did not return messages left at his office and at his home in Bryn Mawr.

Sam Pond has fought strongly against House Bill 18. The contact person for Pond Lehocky's political action committee, Pennsylvanians for Injured Workers, is the law firm's CFO and managing member of Workers First, Bryan Reilly. Since last year, the PAC has received $45,500 from five doctors affiliated with Workers First, Insight Medical Partners, or the Relievus medical network, campaign finance records show.

Unmarked, disappearing pharmacies

At least three of Insight Medical Partners' other pharmacies are located below the Relievus medical practice on Township Line Road in Havertown, just over the Philadelphia border.

One of them, 700 Pharmacy, is partly owned by Miteswar Purewal, as well as Patel and two other doctors in the Relievus network and Insight Medical Partners.

Miteswar Purewal's patients can walk out of his medical practice down a flight of stairs into his pharmacy below. There are no signs on the glass door, but a woman inside confirmed to a reporter that several pharmacies are located there.

Billing records show that 700 Pharmacy has charged similarly inflated prices for medication as Workers First, which used 700 Pharmacy's address when it organized as a limited liability company. Purewal and Patel did not return several requests for comment. Siegel, their lawyer, said in a statement: "Most physicians who participate in these joint ventures have a nominal financial interest, but are comforted by the fact that the pharmacies will dispense medications to their patients despite the obstacles to being paid."

In late July, a reporter visited Insight Medical Partners, the company that manages all of the pharmacies and is part owner of Workers First. The window of Suite 110 in the company's Conshohocken office building included signs for four pharmacies — Empire Pharmacy, Omni Pharmacy, Armour Pharmacy, and Excel Pharmacy — with similar color schemes and identical weekday hours.

On an afternoon in early September, a reporter revisited the Insight office during business hours, seeking comment. The door was locked and the four pharmacy signs had been removed.

A man there buzzed himself into Insight. When asked if CEO Patel was available, the man said no. He was asked if the pharmacies were operating there since the signs were gone.

"I don't feel comfortable sharing that information," he said.

Staff writer Don Sapatkin contributed to this article.