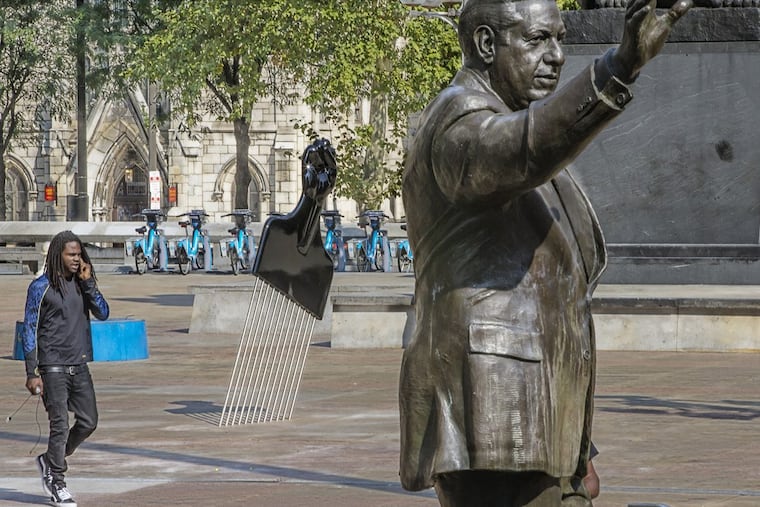

Afro-pick sculpture behind Rizzo statue is anything but empowering

Now that the nearly 12-foot tall stainless steel pick has been placed firmly in the ground about 100 feet behind the city's most divisive mayor, I must say, I'm disappointed.

When I first heard about Mural Arts Philadelphia's plan to put an Afro pick, complete with a clenched Black Power fist, in such close proximity to the controversial statue of Frank Rizzo, I was ecstatic. I thought: The Rizzo statue could stay exactly where it is if this iconic symbol of African American heritage, beauty and strength were nearby.

Push, pull, baby.

But now that the nearly 12-foot tall stainless steel pick has been placed firmly in the ground about 100 feet behind the effigy of city's most divisive — read: racist — mayor, I must say, I'm disappointed.

Sorely.

Before I continue, this is no critique of the work of artist Hank Willis Thomas. On its own, the statue of the Afro pick, titled All Power to All People, is a phenomenal piece of sculpture. In fact, with its smooth ebony handle and strong metal teeth, it's quite the accurate representation of the styling aid that, back in the day, was buried deep in many a defiant Afro (including my Mommy's, my Daddy's, and all my uncles'). These days, Roots drummer Questlove sports one.

Thomas told me All Power to All People was inspired by the Clothespin that sits at 15th and Market Streets. He said he would have been just as happy with All Power to All People in Fairmount Park as he would have been a bustling city. The point was, he said, that there aren't many symbols in Philadelphia that are so iconic to African American history.

However, in an effort to be provocative and probably to take advantage of the bubbling Rizzo controversy, Mural Arts Philadelphia pushed to have the sculpture as close to Rizzo's statue as possible.

That would have worked if the Afro pick were as imposing as Rizzo. Instead, the statue of Rizzo remains like a God to those who worship him and a menace those who fear him. The sculpture of the pick — several feet of which appear buried underground — appears small and afraid. In this context, the Black Power fist — one of African Americans' undeniable symbols of collective stalwartness and fortitude, resistance and perseverance, beauty and might — is reduced to an afterthought.

What a letdown.

Back in the late 1950s, black men and women began growing their natural hair into big Afros to embrace their God-given beauty. And by the late 1960s and 1970s, the Afro was a fashionable and a political statement of resistance to anything and everything that kept black people down.

"I remember back in the day Rizzo would hurt you," said Barbara Easley-Cox, who was once an active member of the Black Panther party. Easley-Cox said she wore her Afro with pride. "A lot of the police officers under Rizzo felt it was their duty to protect white society. We were seen as dangerous. We had no choice but to stand up to him and to fight."

Stand up and fight, not cower in the background.

The original Afro picks, said Lori Tharps, associate professor of journalism at Temple University and co-author of one of the definitive books about black beauty, Hair Story, were simply recreations of African combs.

"Black people looked at Afro picks as a way of reclaiming our history, because it had so long been cut off from us," Tharps said. "And then when the power fist was added, it added an element of protest. That fist said, and still says, we are defending our right to be black."

When I asked Tharps her thoughts on the Afro-pick sculpture, she, like me, was full of black pride and glee.

"It's genius," Tharps said. "It says your statue is not more powerful than mine, and here is my response to you squashing my rights."

But there is nothing powerful about this setup. In fact, it's rather gimmicky. Maybe the sculpture can be a conversation starter. But not as it relates to Rizzo. If you approach Rizzo from the south side of John F. Kennedy Boulevard, you can barely see the Afro pick. And when I stood next to the Afro pick Tuesday afternoon and glanced diagonally to my right, Rizzo's entire powerful back was to me.

Just as the former mayor probably would have wanted it.