Philly streets stained by the blood of the dead | Helen Ubiñas

Maybe the police thought the rain would wash away Frankie's blood.

Frankie's blood did not wash away.

Maybe police thought that it would, the way the rain pounded the pavement that Sunday night. Or maybe the dark had made it hard for them to see the sidewalk, still stained deep red when his family arrived the next morning at Hancock and Susquehanna.

Cops usually make the call to the fire department to hose off the blood. But for reasons that wouldn't become clearer until later, that didn't happen this time.

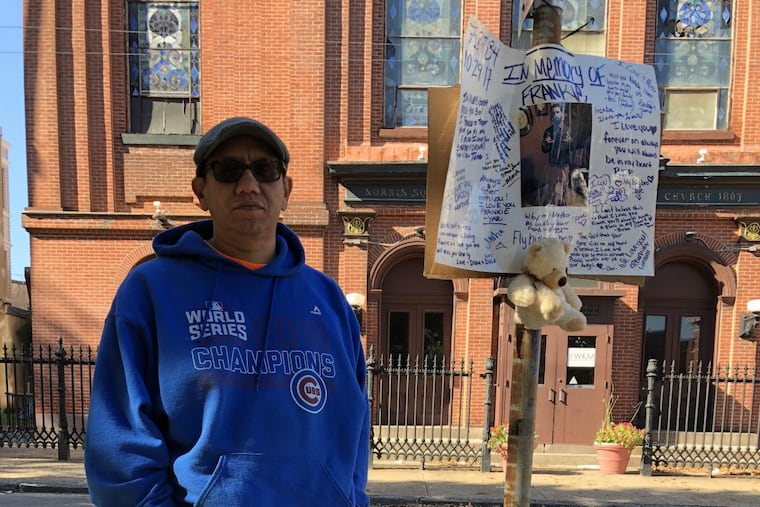

From inside the church across the street, the Rev. Adan Mairena, pastor of the West Kensington Ministry in Norris Square, heard the women on the sidewalk, their voices growing louder, crying. The victim's sister and aunt had come to set up a curbside memorial and instead were stunned to find the remnants of their loved one's violent last moments: shell casings from the gun someone had used to shoot him in the head, blue rubber gloves that the medics likely used to try to save him, and blood, so much blood that no question remained where he had taken his last breath.

The night before, on Oct. 30, Mairena had arrived at the parsonage next to the church to flashing police lights. Officers told him to go inside. He wondered if the body under the white sheet on the ground was someone he knew, a parishioner maybe, God forbid, a kid from the neighborhood.

By now, most everyone knew that it was 33-year-old Francisco "Frankie" Caraballo, whose family lived just a few blocks away. As it happened, he was related to one of Mairena's parishioners.

Some calls were hastily made, to Councilwoman Maria Quinones-Sanchez, to an apologetic district Capt. Krista Dahl-Campbell, who said through a department spokesperson that the officers and investigators on the scene the night before "thought that the rain would wash away the blood." About an hour later, they got a fire truck there to clean the sidewalk. "We will do better," she said.

We can start with making these cleanups less discretionary.

By the next day, only those who knew that someone had chosen that sidewalk to end a man's life could make out the stain. One of Caraballo's cousins sat in his car near the sidewalk memorial, his eyes wet with tears as he talked about his family's loss compounded by the bloodstains left behind.

It was disrespectful, Jeremy Cruz said — to his cousin's life and to his death. His cousin had gotten into trouble for selling drugs in the past, relatives acknowledged, but that was behind him. He was a good guy, a father who left behind a 5-year-old son.

Later, a small group of neighbors gathered around the memorial and talked about how traumatic it was for the dead man's family, but also for the neighbors who had undoubtedly walked past the crime scene while walking their dogs in the park. Not to mention the children headed to a nearby day care and school.

More than a few wondered the same thing: If this had happened in Rittenhouse Square and not Norris Square, would police have been more careful?

They already knew the answer.

Mairena called what happened symbolic of the lives of people in many of Philadelphia's neighborhoods, living and dead. Unvalued.

Five days before Caraballo was killed, and less than a mile away on the 600 block of West Susquehanna Avenue, another man was shot in the middle of the day. For hours on Oct. 24, Kelvin Herrera Delacruz's body lay near a dumpster mere steps from Maria Roman's front door, one of his hands still balled up in a fist. Roman recognized him as one of the young men who had grown up around the area.

After the body was removed, Roman, 59, watched police scatter something on the bloodstain before they left, presumably to break it down. When it didn't go away, Roman panicked.

In 2011, Roman's neighbor Justin Reyes, 17, was shot outside a nearby bodega. Roman worried what seeing the blood would do to his mother, Kathy Lees.

So Roman rushed to clean it up before her neighbor got home. She spent an hour on her hands and knees, scrubbing with bleach until the blood washed away.

When I stopped by, the only hint at what had happened there was a blue rubber glove and some yellow crime-scene tape that could have been mistaken for a Halloween decoration.

Only those who had seen Delacruz's body fall would have known a man's blood had been spilled here.

But the streets are never wiped clean, not entirely.

Whether or not fire hoses scatter the evidence, pushing scarlet pools down the storm drains and into the sewers, Philly's streets are forever stained with the blood of the dead.