Can we save Paul Robeson House?

The museum-homes of Marian Anderson and John Coltrane are also in danger.

I'M A SUCKER for a historic house.

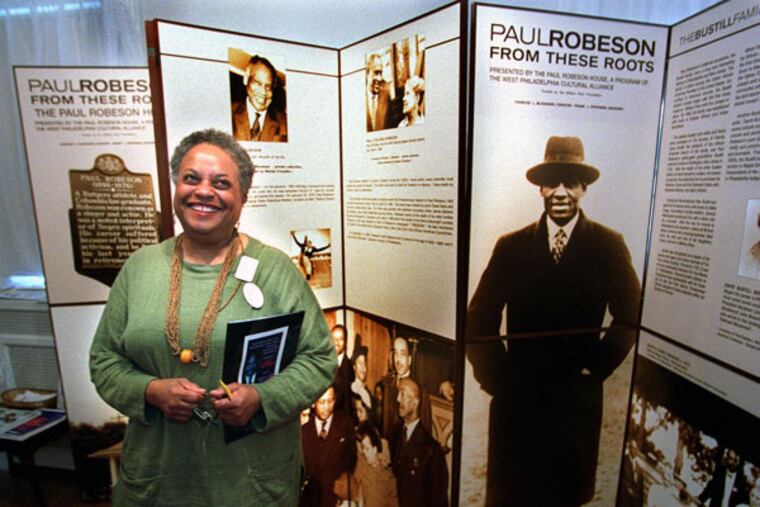

So, when I got word that the head of the Paul Robeson House in West Philly was in failing health, I got concerned wondering who would take over once she was gone.

But before I could set up an interview with Frances Aulston, she died.

She'd fought a courageous battle against cancer. Aulston, 75, left behind a team of dedicated volunteers and a board of directors eager to carry on her mission of keeping Robeson's house open and his legacy alive.

It won't be easy.

Historic house museums everywhere are struggling. West Philly's Paul Robeson House, which doesn't have a single paid staffer, is no exception. Moving forward, the question becomes, "What happens next?" For so many years, Aulston was the Paul Robeson House.

"Who's going to take her mantle? Who's going to carry it on? Because it's very important that Robeson's name and Fran's name be honored in the city of Philadelphia," noted historian Charles L. Blockson said during a recent interview. "It's painful for me. No one will ever replace her. But I hope that we have enough African-American people to maintain her name as well as Paul Robeson's name."

Into thin heir

It would have been better had Aulston lined up a successor. That's what the founder of the Marian Anderson Historical Residence Museum did.

Blanche Burton-Lyles is 82 and recently had a hip operation. But there are lots of changes underway at the tiny rowhouse on 762 Martin Street near Catharine in South Philadelphia, where Anderson grew up.

The museum, which used to be open by appointment only, now has regular visiting hours.

Exhibits these days change regularly and visitors can now arrange to have a meal in Anderson's home as they watch a flat-screen TV of Anderson's historic concert performances and peruse old newspaper clippings and memorabilia relating to the legendary singer's career.

All of that is possible because in 2013, Burton-Lyles appointed Jillian Patricia Pirtle, 32, a 2004 graduate of the University of the Arts and a former participant in the house's young scholars program. Pirtle, a professional singer who uses Jillian Patricia as a stage name, is lively and full of ideas. After agreeing to take over, Pirtle immediately went through the museum's photo archives and came up with themed exhibits to encourage repeat visitors.

Pirtle also improved the website, set Burton-Lyles up on Facebook and established a page for the house. She opened accounts on Instagram and Twitter and even talked Burton-Lyles out of her old flip phone.

"My whole goal is to let everyone know that the museum is here and that Philadelphia should embrace it," Pirtle explained. "I believe that Marian Anderson was just as important as Betsy Ross and the same attention should be paid."

Anderson was an accomplished singer who in 1939 became an international symbol of racial bigotry after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to let her perform at Constitution Hall. Anderson died in 1993, but her legacy lives on.

During Pope Francis' upcoming visit to attend the World Meeting of Families, Pirtle has scheduled hourly, live performances during which she'll sing "Ave Maria," a song Anderson is known for performing. She'll be accompanied on the piano by Burton-Lyles, a former concert pianist who, as a child, played for Anderson's house guests.

I stopped by recently to see some of the changes Pirtle had instituted. I oohed and awed over baubles and tiny shoes once owned by Anderson now on display in what had been storage space before Pirtle took over. I fingered an elaborate, high-necked wedding gown worn by Anderson in 1943 when she married architect Orpheus H. Fisher. Pirtle discovered it last year while doing some cleaning for Burton-Lyles.

Anderson's living-room walls, which had been mostly bare, now are covered with photos of Anderson's travels around the world.

The best part, though, was the feeling of energy percolating through the house as Pirtle laid out a light lunch. As I perched on an antique chair in Anderson's sitting room, Pirtle positioned herself next to a grand piano and sang a piece from Giacomo Puccini's opera "La Boheme" as Burton-Lyles accompanied her on the piano. For that, I gave her a one-woman standing ovation.

Knowing that Burton-Lyles used to host similar concerts for Anderson in the same space made the experience special.

Robeson's impact

The son of a runaway slave-turned-minister, Robeson achieved international fame as an actor, singer and human-rights activist.

He studied law at Columbia University while playing in the NFL. Discouraged by the racial prejudice he experienced working as a lawyer, he left the legal field to pursue a career in the arts. In 1924, he starred in Eugene O'Neill's controversial play, "All God's Chillun Got Wings." That was followed by his role as Brutus in "The Emperor Jones."

His first film was 1925's "Body and Soul" by Oscar Micheaux. He became a darling of the Harlem Renaissance, socializing with the likes of poet Claude McKay.

Fame was no protection from racism. Robeson used his international platform to speak out against such injustices and challenge the notion that blacks should serve in a military run by a government that tolerated racial prejudice. The House Un-American Activities Committee eventually accused him of being a Communist and in 1950 revoked his passport. He was blacklisted.

By the mid-1960s, he was in failing health. His sister, Marian Forsythe, invited Robeson to live with her after Robeson's wife died. He moved into the house on Walnut Street in 1966 and stayed there until his death at age 77 in 1976.

Landmark decisions

When Tyree Johnson, editor of the Westside Weekly, heard that Aulston was looking for space to house the West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance, he suggested the Robeson House which was empty and dilapidation. Squatters had taken over.

But Aulston recognized what it could be. Funding to purchase the property came from a Save the Treasures grant administered by the National Park Service.

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission declared the house a historical landmark in 1991. Open by appointment only, it's also a national historical landmark.

"I've seen her when she didn't have enough money to pay the electric and lights," Blockson recalled. "And then they gave her trouble about the roof. She used her own money.

"It was Fran who saved it."

For years, I planned to go see the Robeson House, but you need an appointment. I finally got around to visiting earlier this summer.

After so many years of looking forward to going, I left a little disappointed. I expected more period furnishings or perhaps a recording of Robeson singing "Ol' Man River" as I climbed the stairs.

But I could get into Robeson's House. While reporting this column, I tried to arrange a visit to another National Historic Landmark, the John Coltrane House. I called. I emailed. I even knocked on the door of the house where the jazz saxophonist lived from 1952 to 1958, but couldn't find out anything about it.

Helen Haynes, Philadelphia's chief cultural officer, told me she's been in talks with the Pennsylvania Council of the Arts to provide a consultant to do an overall assessment of the Robeson House.

"Then we will be developing a transition plan for the organization," Haynes said. "She [Aulston] has only been gone a few weeks.

"You have to understand that they are still grieving," Haynes said. "Fran worked with them up until the end. It's still very raw."

Meanwhile, the head of the Paul Robeson House board of trustees vowed to not let up.

"The legacy of Paul Robeson exists independent of Frances," said Mitchell Swann, a partner with MDC Systems, a Paoli-based international construction claims management support firm. "The expectation is we are going to continue and try to march forward. It's not going to disappear. We are not going to become a Chick-fil- A."

On Twitter: @JeniceArmstrong

Blog: ph.ly/HeyJen