At Stockton, good start to a conversation over slave-owning namesake

At Stockton University, a soul-searching has begun over the fact that its namesake, Richard Stockton, owned other human beings.

Stockton University is named for Richard Stockton, who signed the Declaration of Independence and was put in chains by the British.

Less well-known is the fact that, as a slave owner until his death, Stockton himself kept other human beings in bondage.

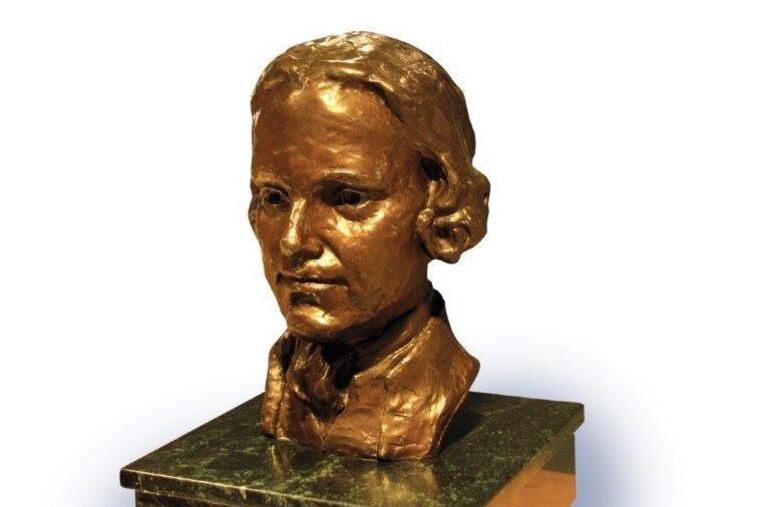

In late August the university announced it had "temporarily" moved a bust of the eloquent Princeton lawyer and accomplished swordsman from a prominent spot in the lobby of the library on the main campus in Galloway Township.

The abrupt action sparked complaints from some alumni and others — there were cries about those legendarily nefarious liberal "snowflakes" sanitizing history, etc. — as well as expressions of support.

And last week, university president Harvey Kesselman selected a group of Stockton administrators, educators, and students to work with volunteers from the larger community and determine where and in what manner to utilize the bust in telling the fuller story of the school's flawed namesake.

This strikes me as an eminently sensible and not overly sensitive notion.

"We are not ignoring or revising history here," says Kesselman, who was named Stockton's president in 2015 after more than three decades of service as a faculty member and administrator at the institution he unabashedly loves.

So far, "the conversation has been civil, thoughtful, inclusive, and supportive of Stockton University," Kesselman says. The school serves a total of nearly 9,000 students at its Galloway, Atlantic City, Woodbine, and Manahawkin facilities and is building a residential campus in Atlantic City as well.

An early alum — he attended classes in Atlantic City's Mayflower Hotel while the Galloway campus was under construction in 1971 — Kesselman also says Richard Stockton's history of slave ownership has long been known and discussed at the school.

But the national uproar over the dismantling of Confederate statuary spurred his decision to move the bust and appoint the eight-member Stockton Exhibit Steering Committee, which he describes as diverse.

"This is a strong leadership move … to begin change by looking in the mirror," says R. Akbar, an attorney and actor who grew up in Philadelphia and graduated from Stockton in 1987. He served for two years as student government president and was the first African American to hold that position.

"What is beautiful about the exploration" his alma mater is undertaking, Akbar says by phone, "is that we all get to learn more about not only Stockton, but the history of the university."

Founded as Stockton State College — with a woodsy setting, groovy architecture, and progressive '70s ambiance — the school was rebranded as the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey in 1993. A few years later, the bust by the late sculptor Joanna Gichner Kendall was put on a pedestal in the library lobby; in 2015, the state upgraded Stockton to university status.

I found plenty of online biographical material about Richard Stockton that praises his patriotism and professional skills, but little mention of the fact that he owned slaves. The practice was lamentably common among the era's agrarian gentry, Northern as well as Southern, and many if not most signers of the Declaration of Independence owned Africans who had been enslaved.

What's also often omitted from typical narratives about Stockton: The enduring question of whether he betrayed the Revolutionary cause in exchange for release from his brutal incarceration — an arguably inconvenient truth that led one independent historian to suggest last year that removal of a sculpture of Stockton in Washington ought to be considered.

In his book Abductions in the American Revolution (McFarland, 2016), Christian M. McBurney says New Jersey might want to replace the figure of Stockton in the Capitol building's National Statuary Hall with a less problematic state luminary.

"[B]ecause strong evidence indicates that [Stockton] signed an oath of allegiance to the Crown, I do not believe he should be celebrated as one of New Jersey's greatest heroes," McBurney wrote in a story published in the Journal of the American Revolution.

Nevertheless, "I'm concerned that the university took this step [removing the bust] without providing background evidence that Stockton was a slave owner," McBurney tells me by phone from the Washington suburbs.

I have no problem with the sequence of events on campus; I also believe the process beginning to unfold is well-intentioned and wise.

Having grown up in Massachusetts, where Paul Revere dominated Revolutionary War history, I knew hardly anything about Richard Stockton. But I'm learning more — there's much to admire about the man — and expect others will be doing so as well.

Stockton grew up in a wealthy Princeton family and was educated at the College of New Jersey, an institution his father helped establish (it later became Princeton University). He was admitted to the bar, became a judge, and raised six children with his wife, Annis, a widely respected poet.

Yet a published abstract of his will includes a revealing sentence: "My wife may free what slaves she wishes."

Just like that.

"What slaves."

In the abstract, the individual slaves aren't named.

I don't know whether Annis Stockton did as her husband apparently intended.

Perhaps the Stockton Exhibit Committee will spur researchers to find out.

And perhaps such information can help educate students and others who wish to contemplate the bust of Richard Stockton where it belongs — on the campus of the university that bears his name.