Demolition's underway, but loyal grads push to save Camden High's "heart"

Opponents see the demolition of Camden High School as a symptom of the privatization of public education. But supporters say a century old building will be replaced by a "world class" public education facility

As workers took apart a portion of Camden High School a couple of blocks away, Kelly Francis made a powerful case for saving the beloved institution's century-old heart.

"Destroying Camden High would be the same as what happened to our ancestors when they were brought here [as slaves] and separated from their history," said Francis, 83, a 1952 graduate whose two sons also are Camden High alums.

Built in 1916 at Park and Baird Boulevards, the Gothic landmark nicknamed "the Castle on the Hill" was one of the few places where blacks and whites from segregated neighborhoods across the city met, mingled, and shared a first-rate public resource in the early decades of the 20th century.

Camden High was where generations of African Americans "were given a foundation for excellence," said Francis, a longtime member and officer of the Camden County NAACP.

"So much of Camden has been torn down," he said. "Our neighborhoods were torn down, wiped out."

This painful history is one reason some city residents oppose the $136 million project to raze Camden High and build a 1,200-student campus of four smaller high schools, including Brimm Medical Arts and Creative and Performing Arts, in its place. It would be the first entirely new public high school constructed in Camden in 100 years.

The state has been overseeing the city's public school system since 2013 as enrollment has risen to 9,000 at public charter and Renaissance schools while falling to 6,500 at traditional district schools.

Since 2007, a state plan to renovate Camden High has been announced and then scrapped, the building's central tower has been repaired at a cost of more than $3 million, and the plan to tear down the tower and the rest of Camden High to make way for an altogether new facility has been put in place.

So despite the Camden advisory school board's declaration that the new high school "shall remain utilized as a traditional district school," some residents are convinced it will become a Renaissance school anyway, or won't be built at all.

"It's [like] taxation without representation," said Mo'Neke Singleton-Ragsdale. She and Vida Neil and other public education advocates are fighting to save the 1916 portion of Camden High.

Demolition of a newer wing and other additions would free up plenty of space to build "a state of the art facility behind the Castle," said Singleton-Ragsdale, who has written to Gov. Murphy and Lt. Gov. Sheila Oliver asking that the original structure be spared.

"I ask you … [to] intercede on behalf of our community and save the residents of Camden from the loss of our history, the bridge to our elders and [the] shared identity that Camden High represents," she wrote.

The school closed after graduation last spring, and fewer than 400 students are now attending Camden High classes in the Hatch Middle School building.

In September, the New Jersey Schools Development Authority authorized the start of demolition of the shuttered complex. A lawsuit to prevent the demolition was dismissed in U.S. District Court in Camden in November. And last week, the district released handsome renderings of a new facility, complete with a tower that echoes the original.

"We explored every available pathway to preserving the facility. I would love to have been able to do that," said Paymon Rouhanifard, the state-appointed superintendent of the city school district. He also volunteers as a Camden High basketball coach.

Rouhanifard said it would be "next to impossible," financially and otherwise, to retain the original portion of the school and incorporate it into a new campus, particularly given decades of deferred maintenance.

"We are incredibly mindful of the history," he said. "People have made suggestions about [architectural] elements to save and incorporate into the new building, and I'm confident it will be ready in 2021.

"Our kids deserve this. They deserved it a long time ago."

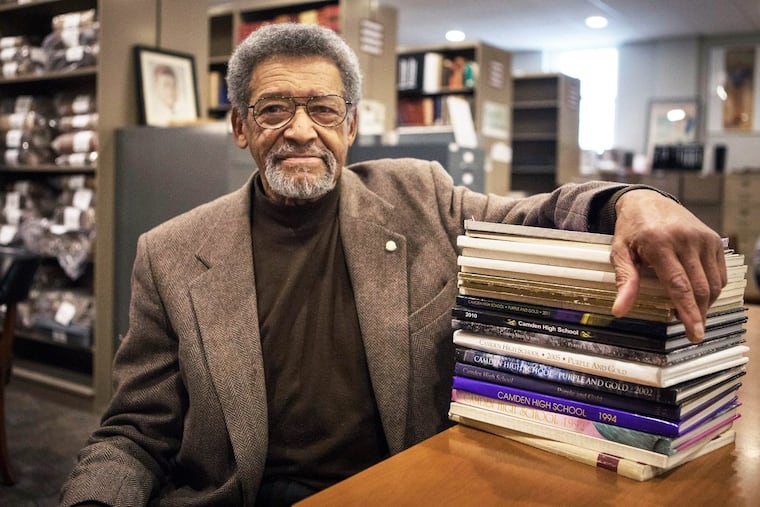

One morning last week, Francis and I met at the Camden County Historical Society's library, on Park Boulevard just east of Camden High. We leafed through a stack of Purple and Gold yearbooks from the 1920s through the 1960s.

His own 1952 yearbook reminded Francis of a story — about how a guidance counselor tried to steer him away from college prep courses toward something more — "suitable."

"My mother insisted. She wanted me in college prep," said Francis, who attended Pennsylvania State University. "There were only two black boys in college prep while I was at Camden High."

Francis pointed out prominent African American graduates such as Bruce Gordon (Class of 1964), who became national chief executive of the NAACP, and Leon Huff (Class of 1960), founder with Kenny Gamble of Philadelphia International Records.

Countless other black men and women were educated at Camden High and went on to serve in the military, in law enforcement, the judiciary, "and in every profession," he said.

"We're just scratching the surface," he said. "There are so many stories."

I've known Francis for nearly 30 years. I deeply respect him, and the service he and his allies in the preservation fight have rendered to their community.

I agree that the loss of yet another Camden landmark — and this one in particular — is painful. But I believe the gain will far outweigh the pain.

"I'm not going to say there's no validity to the concerns about history," said Rashaan Hornsby, a Camden High Class of '99 graduate who serves on a 50-member community committee advising the district on the new school project.

"I'm not so attached to the building," he said. "I'm more concerned with the name, and the brand, if you want to call it that.

"As long as the kids get a great school," Hornsby added, "I think it's a win."

So do I.