The story and significance of Sixers-Celtics in NBA playoffs series and the best chant in sports | Mike Sielski

It was begun during a memorable Sixers victory over the Celtics in Game 7 of the 1982 conference finals, by three men in Boston Garden's cheap seats, and it's a reminder of what graciousness and respect look like.

It was one of the most memorable moments in sports, fresh then and familiar now, for its spontaneity and its context and its graciousness. You've heard it, right? Sure, you have. And maybe you first heard it on a Sunday afternoon in May 1982, as it drifted down from the rat-infested rafters of a stinking hot arena, from somewhere above a basketball court riven with flood-board cracks and dead spots, from three guys who wanted to pay respect to a team that they weren't even rooting for.

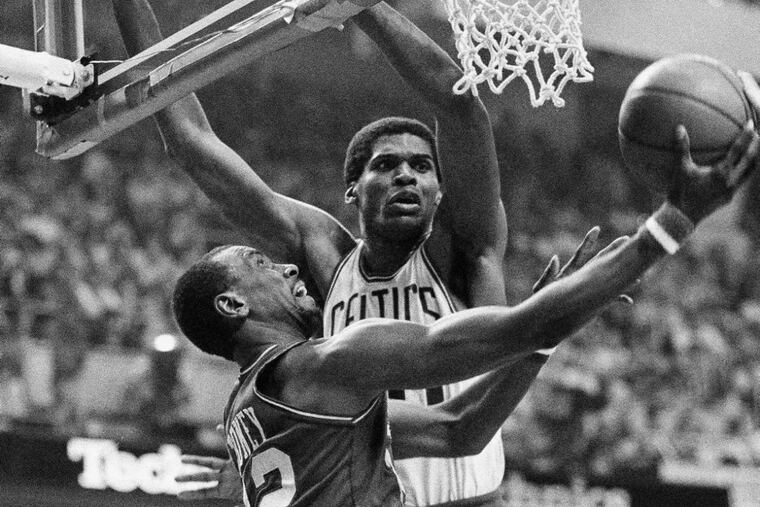

Set the scene: The 76ers are leading the Celtics by 12 points with 26 seconds left in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Finals. Danny Ainge hits a three-pointer. Caldwell Jones throws the ball away on his ensuing inbounds pass. The action pauses. These details are incidental. The Sixers will win, 120-106, and everyone in the old Boston Garden knows that the Sixers will win. Coach Billy Cunningham is piston-pumping his fist; his team will face the Lakers in the Finals. Larry Bird is slumped on the Celtics' bench; a year after winning his first NBA championship, he and his team are going home. And those three guys in the bleachers make a noise that still resounds nearly 36 years later.

[ An old rivalry comes to life in a new NBA ]

"We started the chant," Joel Semuels said, "and other people started chanting."

The chant, of course, was "BEAT L.A.," and its genesis has been a defining episode in Sixers-Celtics history ever since. Other fan bases have appropriated the chant; it gets recycled often. But its roots remain embedded in what was basketball's best and most fevered rivalry, so much so that on Monday night, ahead of their 117-101 victory in Game 1 of the conference semifinals, the Celtics draped a green "BEAT PHILA" T-shirt over every seat in TD Garden.

Semuels, 71, a retired attorney from Belmont, Mass., has long taken credit for the chant's creation, sharing its origin story with his daughter Alana, a staff writer for The Atlantic, who re-shared it last October. In his telling, he and two family friends, brothers Bob and Rich Weintraub, shared Celtics season tickets in the balcony. "In the new Garden, the balcony is way far back from the floor, but in the old place, it was right on top of the floor," Semuels said recently in a phone interview. "There were three decks, and when people were standing and screaming, you could hear cheering for five minutes, and it would rattle the entire Garden."

Like everyone else who was following the series, Semuels and the Weintraubs entered Game 7 confident that the Celtics would win. In the 1981 conference finals, Boston had rallied from a three-games-to-one deficit to eliminate the Sixers, and the same scenario appeared to be playing out again in '82. The Sixers led three games to one before Boston routed them in Games 5 and 6, and it felt inevitable that the Celtics would finish them off. (When asked why he would bother going to Boston for Game 7, former Inquirer columnist Bill Lyon said, "For the same reason that you agree to be a pallbearer.")

Having the Celtics reach the Finals would be particularly satisfying because — unlike in 1981, when the Houston Rockets represented the Western Conference — Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and the Lakers were waiting. "I really didn't like Los Angeles and their Hollywood approach," Semuels said, "with Jerry Buss and the cheerleaders and Pat Riley and the air-conditioned Forum." But then Andrew Toney scored 34 points. And Julius Erving scored 29. And as the Sixers pulled away in the fourth quarter, Semuels and the Weintraubs decided that if the Celtics couldn't beat the Lakers, having the Sixers do it would be the next best thing.

"We said, 'Oh, s—. The game's over. We're not going to get a chance to play L.A.,'" said Bob Weintraub, a lecturer in Boston University's School of Education. "I don't know how it started, but the three of us were doing it loud. That whole era was the Sixers, the Celtics, and the Lakers. They completely dominated the league. It was amazing. I have this love in my heart for the Sixers. I loved that team."

That the Sixers didn't actually beat L.A. until the following year is immaterial. What made the chant great is that it was flavored with grudging but genuine respect, with affection for a formidable opponent. It was a display of pure sportsmanship. Would such an episode repeat itself today, in our ever-fragmented and insular culture? I'm not sure.

It's hardly surprising, for instance, that the Celtics ignored the chant's original meaning and recast it on those T-shirts with an anti-Philadelphia bent. Having celebrated five Super Bowls, three World Series, an NBA championship, and a Stanley Cup since the end of 2001, Boston sports fans have strutted around with their chests puffed out for a decade-and-a-half. All that success has made a once-sympathetic fan base arrogant and insufferable, and the Celtics were only too happy to cater to that group's own substantial self-regard. Yeah, we were wicked classy once. And if you presume Philadelphia is immune to such haughty tribalism, just remember the most popular and resonant line from Jason Kelce's speech at the Eagles' Super Bowl parade: No one likes us. We don't care.

"Fans are all over the opposition in the media and tweeting," Semuels said. "You hear, 'Yankees suck.' That shows a total lack of respect for the sport, for the team, for the players. It shouldn't be that way."

No, it shouldn't. And it's good, given the chance, to remember a moment when it wasn't.