How can Ed Rendell support safe injection sites when he locked up crack users as district attorney? | Solomon Jones

We must help addicts get into treatment. We must support rehab programs that work. No one ever stopped using drugs by continuing to use drugs.

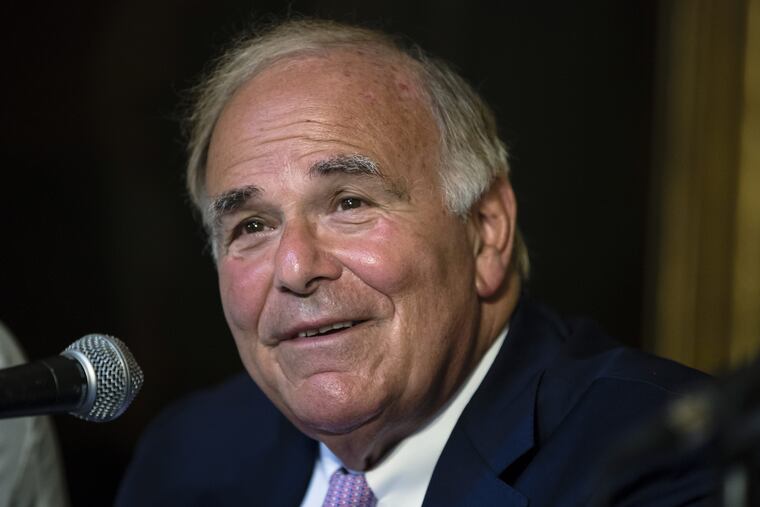

Ed Rendell, who enforced drug laws as district attorney and mayor in Philadelphia during much of the war on drugs, now chairs a non-profit seeking to open a safe injection site where addicts would be able to use illegal drugs under medical supervision.

In my view, that's the height of hypocrisy.

How can you build a career on arresting people involved in drugs and then decide to help addicts to use drugs?

To be sure, the 1,217 overdoses that occurred in Philadelphia last year, many from opioids, are at the heart of the issue. As Mayor Jim Kenney and District Attorney Larry Krasner have both acknowledged to me in radio interviews, the fact that most opioid overdose victims are white is driving greater interest in solving the crisis.

Unfortunately, that interest wasn't there when crack was the drug and addiction was considered a black issue. I reached out to Rendell to ask why he approached crack differently when he was mayor.

"There was no remedy offered to me for users to prevent their dying from crack," Rendell said. "If there was a remedy, I would've considered it. We had no remedy other than to do arrests."

Rendell argues that crack addicts who were arrested were directed toward help. Like most people in Philadelphia's black and brown communities, I don't remember it that way. I remember mass incarceration fueled by black bodies being stuffed into prisons in the war on drugs.

But Rendell says he wasn't just about jailing people. He touts his 1992 executive order empowering Prevention Point Philadelphia to give out clean needles to heroin addicts to prevent the spread of AIDS through dirty needles.

"The same arguments that were made then are being made around safe injection sites," Rendell told me. "I believe they're being made in good faith, but I believe this will save lives — between 25 and 75 a year."

But what about the other potential overdoses? How would opening such a site make a dent in them when city statistics show that 75 percent of Philadelphia overdoses happen in private residences, and not on the street?

Rendell and others are willing to break the law for an idea that probably won't help the vast majority of overdose victims.

Things were different when Rendell was mayor.

Rendell was Philadelphia district attorney from 1978 to 1985, then became mayor 1992, a year after the federal indictments of 26 members of the Junior Black Mafia (JBM) — a notorious drug gang whose murderous reign was inextricably linked to the crack era.

"This is a crushing blow to the JBM leadership, but our work is not done," Deputy Police Commissioner James Clark told the Associated Press at the time. ″We want to make sure no one takes their place."

But the dismantling of JBM created a power vacuum in Philadelphia's crack industry, and as mayor, Rendell was left with streets soaked in the blood of dealers battling for dominance.

From 1992 through 1997, there were more than 400 murders a year in the city. Many of these murders were tied to the struggle for power among Philadelphia's rival crack dealers. I know, because I was on Philadelphia's streets for several of those years, suffering through a crack addiction of my own.

I watched as black and brown people caught in intractable poverty were seduced by the lure of drug money. Many lives were lost. As mayor, Rendell's response was the approach one would expect from a former district attorney. He sought to uphold law and order. Even when the cases were federal rather than local, Rendell made sure we knew where he stood.

In a 1997 case, U.S. v. Edwin Ramos, the Ramos drug organization had sold more than 15 kilograms of crack cocaine on the 1700 block of Mount Vernon Street. Rendell personally testified at sentencing. He called for "no leniency" in that case.

Now, the same Rendell who called for no leniency is chairing an organization that seeks to enable drug dealing by giving addicts a place to use illegal drugs.

This is tantamount to helping addicts die slowly rather than quickly.

Because a life on drugs is no life at all.

Philadelphia's heroin crisis grew to this point because city officials were willing to look the other way as long as drug dealing was confined to black and brown communities.

Now that the majority of overdose victims are white, those same officials are declaring an emergency.

We must help addicts get into treatment. We must support rehab programs that work. But no one ever stopped using drugs by continuing to use drugs. Rendell should know that. After all, he was the man in charge of jailing those involved in the drug trade.

And if Rendell now wants to break the law to a impose safe injection site on Philadelphia, maybe he should face prosecution, too.

Solomon Jones is the author of 10 books. Listen to him weekdays from 10 a.m. to noon on Praise 107.9 FM. sj@solomonjones.com: @solomonjones1