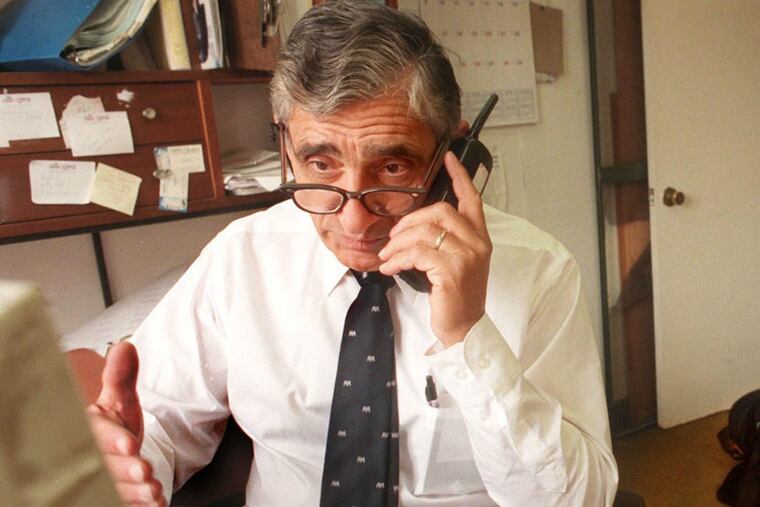

Jimmy Tayoun made his own rules | Stu Bykofsky

The legendary lawmaker and lawbreaker, who died Wednesday at 87, deeply believed in public service and used his office to help people, but didn't follow all the rules.

Jimmy Tayoun was an ex-con, and I know that some will resent my using that term in the first line of this appreciation.

But the legendary lawmaker and lawbreaker, who died Wednesday at 87, would not be among them, because he often introduced himself that way. He did the crime — racketeering and mail fraud and obstruction of justice — and he did the time, soft time at an upstate minimum-security lockup, where he busied himself with kitchen duty and with writing a book.

"Don't mention about me writing the book," he told me during one of our occasional phone calls during his time away. "We're not allowed to write books."

That kind of sums up Jimmy — drawing outside the lines and being too trusting of people. Me? I kept his secret.

It was no secret that most people got to know his name through the Middle East, the restaurant and belly-dance emporium that moved to 126 Chestnut St. in 1969 after a run in South Philly. The Tayouns were Lebanese Christians.

Active in brass-knuckles South Philly Democratic politics, he was elected to the state House, then City Council.

Jimmy deeply believed in public service and used his office to help people, but didn't follow all the rules.

A restaurant owner near the Middle East complained to Jimmy he was having trouble getting approval from L&I for a lighted outdoor sign he needed for his business.

"Put up the sign," Jimmy told the businessman.

The businessman responded: "What about L&I?"

"We'll take care of that later," Jimmy said — and did, with a phone call to a pal at L&I.

"The guy needed the sign, so I helped him out," Jimmy told me.

"But what if everyone did that?" I asked.

Jimmy smiled patiently at me. "But everyone doesn't do it," he said.

After he did his time, he came out of prison fit — daily workouts — and with his 1994 book, Going to Prison?, promoted as "a practical guide for the first-time offender to help ease the transition to prison life and answer all the questions that arise following a guilty verdict or plea."

He launched the Public Record, a weekly newspaper devoted to the joys of local politics, and he didn't play favorites. He treated everyone fairly. Before the Mummers Parade got restructured, he had a massive New Year's open house in his South Broad Street brownstone.

Everyone knew Jimmy, and just about everyone liked him.

His advice was sought (and could be bought) by candidates for public office because Jimmy was a keen strategist and he had favors scattered all over town.

I owed him one myself.

In 1989, the Rolling Stones were starting their worldwide Steel Wheels concert tour in Philadelphia — and had taken over Veterans Stadium, where they were building their sets and props. I wanted to get in, but security was at every entrance.

The stadium was in Jimmy's district. I called and asked if he could get me in. "Put on a suit and I'll pick you up," he said.

He did, in a big car with a City Council shield on the bumper, which he drove right to the gates of the stadium. The workers stopped what they were doing to flock around the car and say hello to Jimmy.

The car was escorted in, I pretended I was Jimmy's aide, I took notes, and got my story.

After it ran — the first look inside the Stones tour — I called Jimmy and told him I owed him one.

"No, you don't," he replied. "You're a constituent."

Actually, I was, but I think he would have helped any reporter who asked.

He was that way — kind, and one of a kind.