Changing Trump’s America starts with house-to-house combat to change Harrisburg | Will Bunch

America's most fraught mid-term elections in modern memory, the war that may make the most difference is taking place under the radar screen – young energized candidates trying to wrest control of state legislatures from conservative, corporatist control.

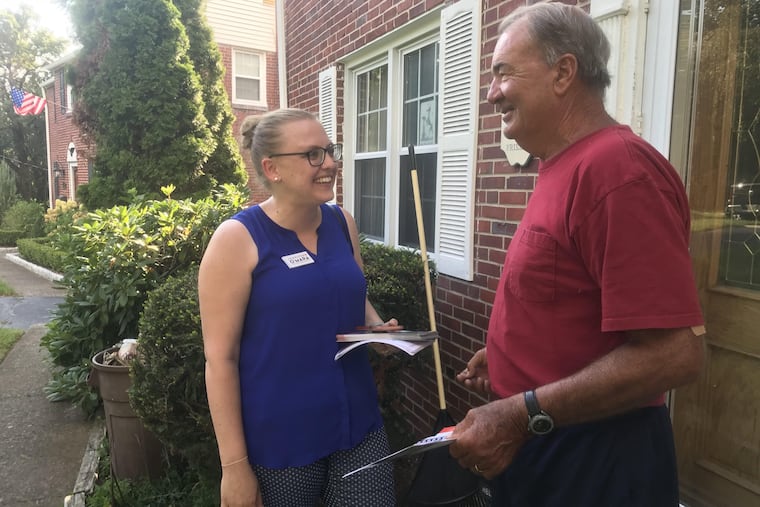

It was a wretched night for campaigning — 95 degrees, sticky — but with the two-month sprint from Labor Day to Election Day now underway, Jennifer O'Mara felt she didn't have much choice but to pull her hair back, throw on her red walking shoes, and make her away around the sturdy brick post-World War II Colonials that line this Springfield cul-de-sac like red Monopoly pieces.

The first stop near the end of the street didn't look promising. Two large dogs barked incessantly before John Houton, a retired refinery worker in a steamfitters' union T-shirt, finally came to the door. "OK," Houton said, arms folded, as O'Mara launched into her standard spiel about why she's running as a Democrat for the Pennsylvania State House, challenging a GOP incumbent in the 165th District, in the heart of Delaware County.

Her pitch merged biography with policy, about how she moved with her mom and two siblings to Delco at age 13 after her dad — a Philadelphia firefighter — committed gun suicide and how she wouldn't have made it without her dad's pension, government-aided health insurance, or good public schools.

"My mom got a job as a school bus driver, which was a union job and gave her good wages and benefits to take care of us or we wouldn't have made it — and I'm running now because there are working families all over this county just like mine who deserve a voice fighting for them in Harrisburg," O'Mara said.

Soon the two started talking about all manner of things — their mutual neighbors who've lived on the block since the homes were built in the early 1950s, O'Mara's uncle nicknamed "Louie the Lip" who worked with Houton at the refinery. And then Houton brought up the political issue that really irks him, which has nothing to do with President Trump or the things you see on cable TV, but with the local school district spending thousands of dollars to park its buses on a nearby property.

As O'Mara finally prepares to leave to ring the next doorbell, Houton utters one last thing. "I'll vote for you — don't worry about that."

Welcome to the house-to-house suburban warfare of the 2018 midterms, the totally under-the-radar-screen battle for control of state legislatures, not just in Pennsylvania but around the nation. It's a fight that will help shape America's political maps for the 2020s and determine whether Democrats have any hope of rolling back years of conservative policies on everything from fracking to reproductive rights that have emanated from most state capitols.

You can see the stakes not just from the cul-de-sac level but from 30,000 feet. When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, it was supposed to signal a new Age of Aquarius for a Democratic Party that was only going to grow in strength as America became younger, better educated, and increasingly nonwhite. Instead, it was Republicans who gained close to 1,000 seats in state legislatures during the Obama era, leaving Democrats in complete governmental control of only eight states.

What happened? While Democrats built a complacent cult of personality around the 44th president, it was older, whiter Americans — tending to be more Republican — motivated to actually vote, especially in midterms when the president is not on the ballot. Those turnouts were amplified by a huge Republican spending edge — fueled by the unlimited donations of the post-Citizens United era — paid for by billionaires and corporations who've come to see state capitols as their lobbyist-powered choke valve to shut down popular middle-class ideas.

Pennsylvania has been a case study. During an era in which Obama carried the Keystone State twice (although Trump famously edged Hillary Clinton in 2016) and bucked a GOP 2014 tidal wave by electing Gov. Wolf, Republicans still managed to grow a sizable advantage in Harrisburg — currently up 119-81 in the House and 33-16 in the Senate. The results have been an extreme pro-GOP gerrymander — their congressional map was thrown out this spring by the state Supreme Court — and legislative inaction on taxing natural-gas fracking as done by other states, while lawmakers focus instead on attempts to restrict voting rights or a woman's right to an abortion.

This isn't an accident. In her remarkably timely book Democracy in Chains, Duke historian Nancy MacLean describes how the modern American libertarian movement — born in the school segregation fights of the 1950s and the Southern rallying cry of "states' rights" but brought to 2010s fruition with the billionaire dollars of the Koch brothers — realized early on that state governments were uniquely positioned to tamp down populist ideas.

In Pennsylvania, for example, state legislation prevents Philadelphia from raising the minimum wage or addressing gun safety, while pending bills threaten its soda tax and the city's ability to protect undocumented immigrants.

With downsized news organizations barely covering local races anymore, it seemed as if nothing would ever change the equation — until the election of Trump. The ascension of the 45th president — and anger in places like the affluent Philadelphia suburbs where he's most unpopular — has inspired a surge of new candidates, mostly Democrats, younger and more often female, on every level. With little fanfare, once-forgotten state legislative races have become a ground zero — not just here but in states like Virginia, where Democrats stunned every pundit by gaining 15 seats last year.

Springfield's O'Mara is the archetype for the new breed of state legislative candidate. She's a young (28) first-time office-seeker who has a compelling bio (rising from her working-class struggles to earn a master's from Penn, where she now works in the development office, married in 2017 to a two-time Purple Heart-awarded combat veteran) and who, like many in her cohort, was motivated to run by her newfound fears over what Trump's policies might do.

Her opponent is first-term GOP lawmaker Alex Charlton, a former legislative aide and Springfield Chamber of Commerce head, a cog on the Republican machine that has mostly dominated Delaware County politics since the Civil War. She may have been motivated by the Trump factor, but it's not part of her pitch, and while some of the voters she meets door-to-door do start ranting about the president, many more bring up taxes or preventing the next school shooting.

"I think people are very disgusted with this divisiveness," O'Mara said. "This extreme response by either party disgusts them and what I present to them is a normal working-class person – one of them, dealing with the same issues, that just wants to try and help our community."

That's not how Republican candidates and their strategists plan to spin it. Charlie Gerow, the veteran GOP consultant based in Harrisburg, conceded that voter enthusiasm will probably result in a few pickups for the Democrats, but he also predicted they'll also be hampered by "rabid left-wingers" — a reference to Bernie Sanders-style democratic socialists who won four primary victories in May, including a contested Delaware County race (Kristin Seale in the 168th).

Even a blue tsunami in November won't bring a Democratic takeover in the Pennsylvania Capitol — only half the Senate seats are on the ballot, and while Democrats are spending more money on more races than usual, their focus remains less than the 21-seat landslide they'd need to flip the House. Gerow said he thinks Republican candidates can hold the line by playing up a few achievements — pension reform, easier access to beer and wine — from the otherwise gridlocked Harrisburg, and by banking on the ages-old axiom that all politics is local, even when the president is Donald Trump.

If he's right, Republicans will retain the clout to block serious gerrymandering reform and thus possibly extend their Harrisburg run deep into a new decade. But O'Mara and her gang of other first-time candidates like Seale are hoping 2018 is a year for shattering old axioms.

O'Mara takes heart in the World War II vet she met canvassing the other night, who confided that she'd be only the second Democrat he'd ever voted for.

The first one was Harry Truman.