Why the blood of a 1955 Mississippi murder drenches today’s U.S. Senate race | Will Bunch

The ghost of a 1955 Mississippi murder hovers over today's voter suppression in the South.

The cold-blooded killing of Lamar Smith — which occurred in broad daylight before a crowd of people outside the Lincoln County Courthouse in Brookhaven, Miss., on Aug. 13, 1955 — is still considered an unsolved murder, but only in the most technical sense of the term.

The truth is there wasn't much mystery about it, then or now. The 63-year-old local farmer and veteran of World War I, known as a fearless activist for his black community and for a seminal civil rights group called the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, crumpled from a gunshot in front of dozens of people, including the county sheriff, who saw a white farmer named Noah Smith leaving the scene splattered with the activist's bright-red blood.

Nor is there any debate over why Lamar Smith paid with his life that day. At the instant he was gunned down, the community leader was carrying a bundle of absentee ballots for an upcoming county election, the fruit of his idea for how African Americans in the Brookhaven area could cast votes without the white violence they'd likely encounter at a polling place on Election Day.

The murder of Lamar Smith may have happened 63 years ago — but don't dare call it a cold case. It is one of the most powerful pieces of evidence in a cruel, sometimes violent and still ongoing conspiracy to suppress black votes in the American South, a chain of custody that stretches from the Ku Klux Klan night riders of the 1860s to Selma's "Bloody Sunday" in 1965 to the computer-aided web of purges, restrictive ID laws and shuttered polling places of the 2010s.

In 2018, the blood from Lamar Smith's unresolved murder still splatters the politics of Mississippi and the former Confederate states.

Four years after he was killed, a baby girl was born in Brookhaven named Cindy Hyde. Over the next 59 years, she immersed herself in the politics of a community that bitterly refuses to concede the just cause that Lamar Smith died for.

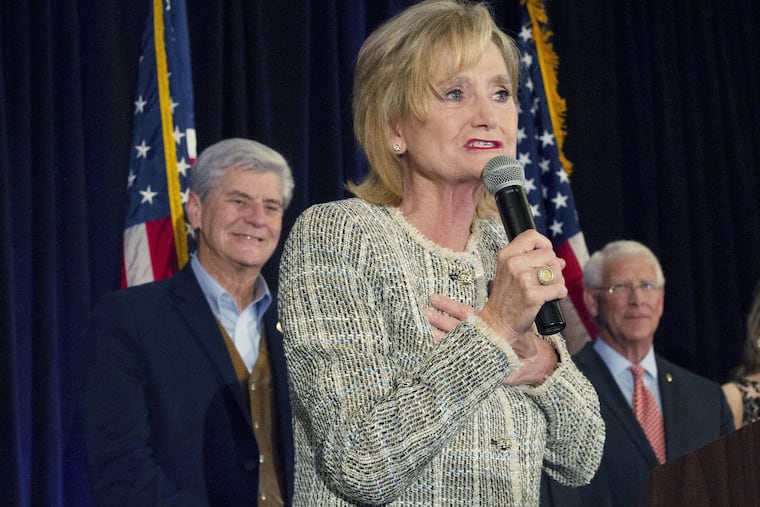

Hyde married a local cattle farmer named Smith — Michael Smith — and as Cindy Hyde-Smith she became a legislator, state agriculture commissioner and, with little fanfare, was appointed this year to replace ailing U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran. She's getting fanfare now. Running in the special election to fill the rest of the term through 2020, the GOP's Hyde-Smith finds herself in the last big contested election of the year, a Nov. 27 runoff with Democratic ex-congressman and cabinet secretary Mike Espy, who's seeking to become Mississippi's first black U.S. senator since Reconstruction.

And under her first real scrutiny, Hyde-Smith has shown that the language of voter suppression and racial oppression runs as deep within the appointed senator as the red-clay soil of the Deep South that her family has farmed for generations. It started not long after the Nov. 6 general election, when a video surfaced from the campaign trail in which Hyde-Smith praised a supporter by saying, "If he invited me to a public hanging, I'd be on the front row." The bizarre remark carried ugly echoes of the fact that more blacks were lynched in Mississippi in the 19th and early 20th centuries than in any other state.

This week, a new campaign video surfaced that disturbingly touches on more modern forms of voter suppression. Speaking to a group of collegiate supporters in Starkville, Hyde-Smith noted that "there's a lot of liberal folks in those other schools who maybe we don't want to vote. Maybe we want to make it just a little more difficult. And I think that's a great idea." The senator later claimed she was joking, but it doesn't sound like it. It sounds, rather, like a public endorsement of a modern Republican crusade to make it harder for people to vote, especially in places — like college campuses — where those people are more likely to vote Democratic.

Hyde-Smith's words were haunted by ghosts of Mississippi past and Mississippi present. The senator emerged from a cocoon in her native Brookhaven that has stubbornly remained emblematic of how Dr. Martin Luther King described Mississippi in his 1963 "I Have a Dream Speech," as "a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression."

"Brookhaven is a different beast," documentary filmmaker Keith Beauchamp told me this weekend. It was Beauchamp's film about a more famous 1955 murder in Mississippi — the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till — that helped convince federal officials to reopen that cold case, and Beauchamp immersed himself in Brookhaven for a subsequent TV documentary on the killing of Lamar Smith, which took place just two weeks before Till's lynching.

Hyde-Smith's invocation of a "public hanging" made Beauchamp cringe because he knew the story of Brookhaven's last lynching in 1928, in which two black brothers — James and Stanley Bearden, accused of assaulting two white men — were seized and murdered by a mob that stormed the county jail. The corpse of one of the brothers was dragged for two miles through Brookhaven's black neighborhoods to intimidate the residents, and then it was hanged, quite publicly.

And local passion for white supremacy flowered again in the 1950s, after the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision to integrate schools as well as rising activism by the likes of Lamar Smith — veterans who fought for America overseas but were denied basic rights at home. Brookhaven was a hotbed of the status-quo-defending White Citizens' Councils that sprung up after the Brown ruling and was home to one of the so-called brains of segregationist movement, Judge Thomas Pickens Brady, whose 1954 tract "Black Monday" — widely reprinted across the South — compared African Americans to chimpanzees and riffed on the sanctity of white Southern women as "[t]he loveliest and the purest of God's creatures…"

That was the frenzied, life-or-death world into which the unbelievably courageous Lamar Smith was martyred, seeking the right for Brookhaven's black citizens to vote. Just three months earlier, another prominent black Mississippi leader, the Rev. George Lee, was murdered by two White Citizens' Councils members for trying to register black voters in the Delta town of Belzoni.

Decades later, a witness told the FBI that the killers ambushed Lamar Smith with his absentee ballots in an apparent setup. Although he was shot at 10 a.m. with a large crowd milling around the Brookhaven courthouse, the sheriff, Carnie E. Smith (by now you may have noticed everyone in this saga seems to be named Smith), didn't immediately arrest the blood-stained Noah Smith or two alleged accomplices, Charles Falvey and Mack (wait for it) Smith. Those three men were later cited but an all-white grand jury did not indict them. The district attorney said it was Sheriff Smith's "duty to take that man into custody regardless of who he was, but he did not do it."

The soil that harbored that injustice would nurture Hyde-Smith as she grew up in Brookhaven during the tumultuous 1960s and '70s. The filmmaker Beauchamp told me he's found loose family ties between Hyde-Smith's in-laws and key players in the segregation fight — that his research shows husband Michael Smith is related to 1955 arrestee Mack Smith and that Michael Smith's sister married the grandson of segregationist judge Tom Brady. None of that is surprising, perhaps, in such a close-knit community. The alleged killer Noah Smith died in 1975 and was buried in Macedonia Baptist Church, the same church where Cindy Hyde-Smith has been a Sunday school teacher.

What's harder to explain is one of Hyde-Smith's first acts during her first term in the Mississippi Legislature in 2002, which was to unsuccessfully push a bill to rename Highway 51 running through Brookhaven as Jefferson Davis Highway, in honor of the slave-owning president of the Confederacy who had no specific tie to Brookhaven. A recent report from the senator's hometown in Mississippi Today notes that even now — when many communities have removed the hot-button Mississippi state flag with its stars-and-bars Confederate imagery — Brookhaven has "doubled down" by flying the controversial banner every 50 yards or so on the town's main drag.

Beauchamp told me that in his extensive reporting on Mississippi he's never seen a wall of silence quite like Brookhaven, both among whites not particularly eager to discuss the past and blacks who may remember more than a century of intimidation tactics all too well. It could be easy to dismiss all of this — the flags, the highway renaming, the bizarre words that come from Hyde-Smith's mouth — as nothing more than cringe-worthy symbolism. But voter suppression in Mississippi — while updated for the 21st century — remains all too real.

Just this year, a Northern Illinois University study ranked Mississippi as still the worst in the nation when it comes to making it hard for citizens to vote — citing factors like its early registration cutoff, lack of early voting, and strict voter ID law. Since Southern states were freed by the Roberts Supreme Court from supervision under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Mississippi has shuttered about 5 percent of its polling places — exactly the kind of thing Hyde-Smith joked about.

Mississippi's voting problems haven't garnered much attention because of the blatant, over-the-top voter suppression that took place in the nearby state of Georgia, where ultra-conservative Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp — in overseeing his own race to become governor — conducted a massive purge of voting rolls and declared thousands of others ineligible in moves that disproportionately targeted blacks. In a race marked by retro incidents like police stopping a bus of black senior citizens headed for early voting, Kemp narrowly beat the woman bidding to become Georgia's first African American governor, Stacey Abrams, and avoided a runoff by a smidgen of votes.

"You see as a leader, I should be stoic in my outrage and silent in my rebuke," Abrams said Friday in acknowledging that Kemp will be the next governor but in refusing to concede, in arguably the most powerful civil rights speech in more than a generation. "But stoicism is a luxury, and silence is a weapon for those who would quiet the voices of the people. And I will not concede because the erosion of our democracy is not right."

Abrams' speech told us that the fight for what Lamar Smith died for 63 years ago is not only not over, but that there is so much more work to do. There is a unique opportunity to begin that work in Mississippi over the next week, to finally bring an end to a sweltering summer of oppression by burying the putrid philosophy of Cindy Hyde-Smith in the red-clay soil where it belongs, and by electing a decent man, Mike Espy, as a symbol of change. That would bring at least one small measure of the justice that Lamar Smith has been denied for far too long.