Finding a way to hope after personal tragedy

LAURADA BYERS still has nightmares, 10 years later, about not being able to save her husband's life. The dreams do not replay the details of the night that Daily News columnist and senior editor W. Russell G. Byers was slain on Dec. 4, 1999.

LAURADA BYERS still has nightmares, 10 years later, about not being able to save her husband's life.

The dreams do not replay the details of the night that Daily News columnist and senior editor W. Russell G. Byers was slain on Dec. 4, 1999.

Byers, 59, was stabbed in an attempted robbery after stopping with his wife to pick up ice cream at a Chestnut Hill Wawa.

"They are nightmares," she said, "of Russell being in a burning building, or of Russell about to fall off a cliff, and I'm not able to save him."

Byers said that one day she hopes to meet with Javier Goode, the man serving a life-without-parole sentence for the killing.

She wants to meet him, not because she has forgiven him, but to bring a conclusion to the story heard by children who attend the Center City charter school that was named after her husband.

"You need hope in life," she said.

It's also a message she tells supporters of the school, which she helped found: That society can either pay to educate children or pay the consequences of young, frustrated uneducated men and women who have no hope.

"It's so sad," she said of Goode's life, which, in a way, also ended that December night.

Goode had been a 19-year-old billing clerk struggling to support a pregnant wife and her two young children before he attempted the robbery.

He pleaded guilty to the murder.

Although Byers has been forever changed by watching her husband die in her arms - "You never truly feel safe," she said - the former real-estate broker and entrepreneur said that she was not going to simply withdraw from life and "stay stuck in that moment."

She decided to take the adversity and turn it into something positive, life-giving and joyful.

She told herself: "I can either say the defining moment of my life is the death of my husband, or I could do something that represents our values and gives back to the city of Philadelphia."

Russell Byers had cared deeply about the issues facing Philadelphia: finances, blight, housing and especially education.

Almost three years before his death, he wrote a column supporting charter schools.

"The Legislature must acknowledge that public education, as we know it, has become a cruel hoax," he wrote on Jan. 14, 1997.

"The Legislature's priority must become education of the public, by any means necessary, and the charter school revolution is an important first step . . . ."

Only three months after Byers' death, Laurada Byers and a group of supporters met to plan a charter school in his memory.

With the help of her children, Russell Jr. and Alison, she opened the Russell Byers Charter School in September 2001.

The school opened in the Spring Garden neighborhood, but two years later, in 2003, it moved to its current location, a large, renovated four-story building on Arch Street near 19th.

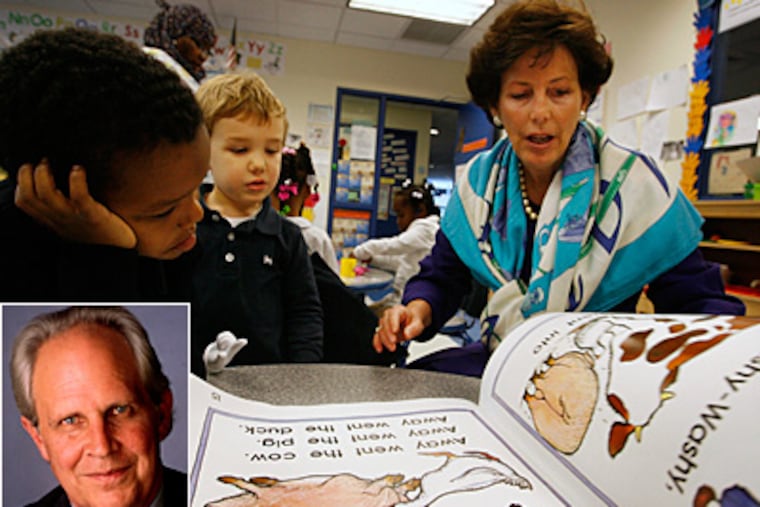

In an open, brightly lighted basement room, large colorful student paintings hang on the walls and stands for musical instruments dot the space. It's in that room that Laurada Byers, a petite woman with dark hair framing a pleasant, smiling face, envisions a school library one day.

Down the hall, there is a studio for ballroom dancing; a computer lab, which still needs computers; and what is to become the Daily News media center.

It is through the school that Laurada Byers wants to help build the hopes for hundreds of Philadelphia schoolchildren and their families.

On the first floor, there is a "Wall of Hopes and Dreams" where students and teachers have written on small wooden placards.

"My hope is to be better at math," wrote Anna Huber, a second-grader. "My dream is to fly."

There are obvious and not-so-obvious ways that Russell Byers' presence can be found in the school.

A vivid portrait of Byers hangs in the first-floor lobby, just above a worn, green-leather chair in which he sat to watch television at home. Now, children sometimes curl up to read in it.

And there are deep-blue tiles scattered among the white tiles in the lobby floor that Laurada Byers said "are the exact color of Russell's eyes."

The school has more than 400 children in grades 4K (that's kindergarten for 4-year-olds) to grade six. Starting at age 4, the children learn Spanish and music along with reading, writing and arithmetic.

The Byers School is based on the "Expeditionary Learning Schools" model in which students learn by doing, and going on field trips to nearby museums.

Yesterday, students in Elizabeth McGuire's sixth-grade class were following up their studies of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by using measuring tapes to "map out" the circumference of the school's lobby.

The oldest Byers graduates are 10th-graders now. And a good number of the alumni attend schools such as Agnes Irwin, Episcopal Academy, Penn Charter and Masterman, a top magnet public high school.

Former students return to meet regularly and to tutor Byers pupils.

But Laurada Byers is already looking beyond a goal of reaching top high schools.

She is trying to raise enough money so that one day she can tell new 4-year-olds and their parents that the Byers School will help finanically when they're ready for college.

It's part of a plan to be able to tell the pupils: "They are ours for life," she said.

CLARIFICATION

Laurada B. Byers, widow of slain Daily News columnist and senior editor W. Russell G. Byers said a recent story may have left the wrong impression about her feelings toward Javier Goode, now serving a life sentence for the murder. "I have forgiven Mr. Goode and have let go of the anger I felt ten years ago. Russell's death was a horribly painfully thing to deal with, but my life has gone on and it's a good life," she said.