Phila.'s Promise Academies have a lot riding on them

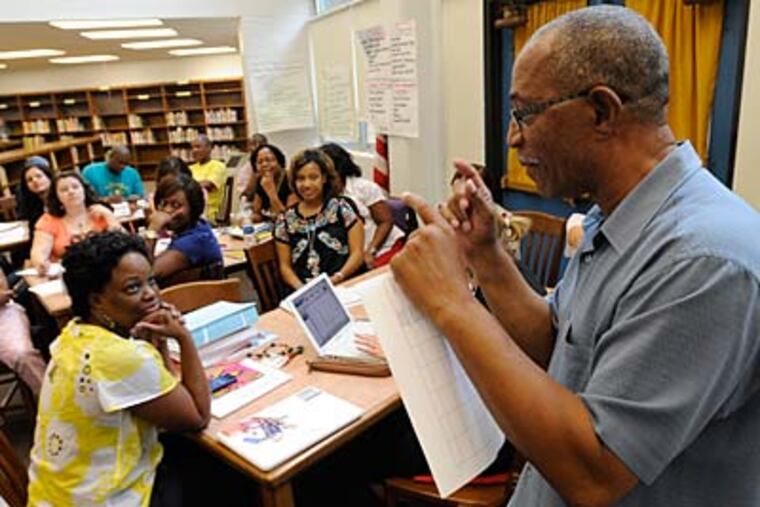

The district is investing more money and resources in six of its 265 schools to try to boost student achievement.

For decades, Philadelphia public schools failed to properly educate large numbers of students.

Superintendent Arlene Ackerman is betting that come Tuesday, the tide will begin to turn for the 2,700 pupils who will start a new term at six Promise Academies.

Ackerman is also keeping a close eye on seven other city schools being taken over by charters. But she takes personally the Promise Academies - overhauled district schools with new teaching staffs, longer days and years, and $7.2 million in extra funding.

"We're giving these students a private-school education in a public-school setting," Ackerman said.

"People look at these schools and their test scores and say, 'Oh, there's an achievement gap,' " said Francisco Duran, assistant district superintendent in charge of the Promise Academies. "I believe there's an opportunity gap."

Students will wear preppy blue blazers and crisp khakis at the six Promise Academies: University City and Vaux High Schools; Ethel Allen, Dunbar, and Potter-Thomas Elementary Schools; and Clemente Middle School. Teachers, who are paid extra to work at the schools, will don uniforms, too.

New books line classroom and library shelves. Lighting is brighter. Even the cafeterias have been spruced up, with more fresh fruits and vegetables and, in some cases, salad bars.

There will be tutoring, an intensive focus on reading and math, and free field trips not just for students but for their families, too. A School Advisory Council of parents and community members will help make decisions.

The children, who are mostly poor and African American, will study a second language. For extracurricular activities, choices will include crew, photography, and hip-hop dance. Teachers will have common planning time. College will be emphasized and parent involvement expected.

Social supports will abound - counselors, behavioral specialists, student advisers, conflict-resolution managers.

Since arriving in Philadelphia two years ago, Ackerman has made it clear that spending more money on struggling students is a priority. At her direction, the district is trying out a weighted student-funding formula, with more money directed toward schools that educate needier students.

The Promise Academies - six schools out of the district's 265 - are an extension of that philosophy.

Even with the extra money, Promise Academies have a long way to go to approach the top suburban districts. Per-pupil spending in Philadelphia is $11,426, one of the lowest figures in the region. The top region's spender, Lower Merion, allots $21,663 per student.

The district could not provide information about how much it will spend per pupil at the Promise Academies.

How widely the district will be able to expand the Promise Academy model remains unclear, especially given the economic slump and a question mark over future Harrisburg funding with Philadelphia-school-friendly Gov. Rendell on his way out.

Also unclear is whether Ackerman's strategy will work. As schools chief in San Francisco, she opened similar Dream Schools beginning in 2004, but they have struggled since she left in 2006.

Vaux parent Teresa Gordy has seen reform efforts come and go in Philadelphia - most notably the district's failed 2002 experiment, in which it handed 45 schools over to private providers. She would like to see this attempt work, but she's skeptical.

"Changing the way they look isn't going to change their mind-set," said Gordy, whose daughter is entering 11th grade. "I'm hoping they're going to reach these kids' minds."

President Obama wants 5,000 failing schools overhauled within five years. In Philadelphia and elsewhere, the stakes are high, said Jack Jennings, president of the Center on Education Policy, a Washington nonprofit.

"These schools frequently have decades of failure. They have high poverty rates, neighborhoods that are dangerous, teachers that don't want to be there," Jennings said. "This is a lofty goal."

The initial Promise Academies were chosen because they were the lowest of a group of low-performing schools.

The initiative is part of Imagine 2014, Ackerman's five-year plan, for which her administration has yet to disclose a total price tag.

The investment in the first six schools must be sustained, Jennings said.

Ackerman is undaunted.

"This is a promise that we're making to these children and their families that we're going to give them a quality education," she said. "They don't have to wait for generations more to see change. It's a renewed opportunity for this school district to do right by these communities."

Ethel Allen principal Woolworth V. Davis understands why some people need persuading.

But he plans on winning them over. "You have to show people that this is different. You have to give them evidence," said Davis, a veteran administrator who left Carnell, a 1,500-student school in the lower Northeast, for the 324-student school on West Lehigh Avenue.

There are miles to go. Just 5 percent of Ethel Allen fifth graders read at grade level. On a visit to the school in the spring, "there were kids everywhere - in the hallways, in the lunchroom," Davis said.

At Vaux, principal William Wade just bought 20 bicycles and helmets for a bike club. When technology teacher Aaron Swan met Ackerman and mentioned he wanted to start a photography club but had no equipment, the superintendent told Swan to send her a list of what he needed. Cameras and lenses are on order.

Steve Feder taught algebra at Vaux last year, and he opted to return for the fall, largely because he feels connected to his students. The staff has been wowed by the support available to Promise Academy teachers, he said.

"We didn't get this kind of funding last year," Feder said. "There's a positive, dynamic feeling."

Wade, who worked as a teacher and administrator in Memphis and Atlanta, was recruited to Philadelphia. He comes to Vaux after a year as principal at the city's Military Academy at Leeds.

Vaux, at 23d and Master Streets amid rowhouses and a public-housing project, is ripe for change, he said. "The community has been frozen for a while and is in need of real leadership," Wade said. "I'm very serious about making a difference in the lives of these kids, who have been disenfranchised for so long."