Penn procedure on sexual assault concerns some law faculty

Nearly one-third of the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania Law School have criticized a new university procedure for handling sexual-assault cases that they say undermines traditional safeguards for the accused and could lead to wrongful disciplinary actions against Penn students.

Nearly one-third of the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania Law School have criticized a new university procedure for handling sexual-assault cases that they say undermines traditional safeguards for the accused and could lead to wrongful disciplinary actions against Penn students.

The procedure, adopted under pressure from the Obama administration, establishes a new position at Penn - the sexual violence investigative officer - and became effective Feb. 1. The policy weakens standards for finding that a sexual assault has occurred, while offering the accused only limited rights to a defense, law school critics say.

Given examples of high-profile sexual-assault charges that have unraveled under close scrutiny, notably the gang-rape allegation at the University of Virginia reported by Rolling Stone magazine, the university must take steps to ensure its procedure for adjudicating sexual-assault cases is fair, the faculty members say.

"Due process of law is not window dressing; it is the distillation of centuries of experience, and we ignore the lessons of history at our own peril," the faculty members said in an open letter aimed at the Penn administration as well as the broader public.

"All too often, outrage at heinous crimes becomes a justification for shortcuts. These actions are unwise and contradict our principles."

Penn declined to provide an explanation for its procedure but did express confidence that it was justified.

"Penn developed the new process as a fair and balanced process to address the serious issue of sexual assault on campus," said Ron Ozio, a Penn spokesman, "and we believe the process responds appropriately to the federal government's regulations and guidance."

Urgent issue

The Penn letter, signed by 16 of the law school's 49 tenure or tenure-track faculty members, comes at a time of growing unease over sexual crimes on American campuses and over the steps that many universities are taking to address the issue under pressure from the federal Department of Education. Its Office of Civil Rights has issued guidelines for the adjudication of complaints that critics contend dispense with long-standing due-process protections. Yet universities, including Penn, face the prospect of losing millions of dollars in federal aid if they fail to adopt the new approach.

Theodore Ruger, the newly appointed dean of the law school, was not among the signers.

"Sexual assault is indeed an important problem, but the federal government has dictated a set of policies and twisted universities' arms into compromising some of the safeguards that we teach our students are essential to fairness," said Stephanos Bibas, a professor of law and criminology and one of the authors of the letter. "There is a tremendous amount of money on the line. It is understandable that universities feel pressure to comply."

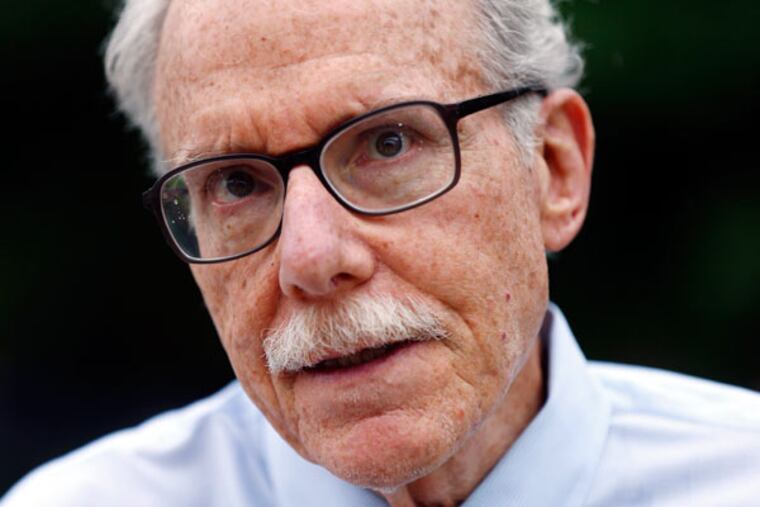

David Rudovsky, a law school faculty member who also practices at a firm that specializes in civil rights cases, said colleges and universities across the country were adopting similar procedures.

"What is problematic about the Penn policy and what colleges are adopting across the country is that they fail, almost all of them, to provide necessary due-process safeguards for persons accused of sexual assaults," Rudovsky said. "We agree that there ought to be protections for persons who complain about sexual assaults. But for those few cases in which the facts are seriously disputed, we know from experience that when you make shortcuts around due process, you tend to get wrongful convictions."

Under Penn's new procedure, the sexual-violence investigative officer, who, working with "one or more co-investigators" drawn from faculty or the administration, will be responsible for investigating all sexual-assault allegations.

That investigative officer has already been appointed. He is Christopher Mallios, a former member of the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office who headed the family violence and sexual-assault unit.

How it will work

Here is how the investigative process will be conducted:

The investigations team will interview both the accused and the accuser and review physical evidence, documentation, and other evidence. Both the parties are permitted to have lawyers, but the lawyers are barred from participating in the interviews and may only offer advice to their clients.

At the conclusion of the investigation, the team will prepare a report and, in determining whether the allegations have been substantiated, employ a "preponderance of evidence" standard, meaning the allegation is more likely true than not.

This standard is weaker than that employed in criminal cases and some civil proceedings. Thus, the new procedure exposes the accused to possible expulsion or other life-changing penalties, only on the grounds the accusation might be true, the letter argues.

The Office of Civil Rights, in a 2011 communication to colleges and universities, required that the preponderance of evidence standard be used and strongly advised schools to ban cross examinations of accusers.

"Allowing an alleged perpetrator to question an alleged victim directly may be traumatic or intimidating, thereby possibly escalating or perpetuating a hostile environment," the agency's letter said.

Colleges and universities for years have had their own procedures for adjudicating sexual-assault cases, in part because some accusations fall short of the standards needed for criminal conviction. But in its letter outlining recommended guidelines for investigating such cases, the Office of Civil Rights said the statistics on campus sexual assaults were "deeply troubling and a call to action for the nation." The letter cited a National Institute of Justice finding that one in five women are victims of sexual assault while in college.

Under the new Penn policy, if either the accused or the person alleging an assault is dissatisfied with the result, he or she can appeal to a hearing panel comprising faculty members. The three-member panel would have the power to take statements from each of the parties, but neither the accused nor the defense attorney could cross-examine the accuser, a key procedure in both civil and criminal trials to establish credibility of evidence.

At the same time, the lawyer for the accused may not make a presentation to the panel, to in effect argue the case of a client.

"Our legal system is based on checks and balances precisely because of the risks associated with concentrating so much power in the hands of a single investigator or investigative team," the letter from the Penn faculty says.

The Penn professors also criticized the process for failing to protect the right of the accused against self-incrimination. Although the accused may refuse to participate in an investigative proceeding, the university may also go forward without taking that person's testimony. The accused then faces the unpalatable choice of either declining to participate or offering a defense in the proceeding, with the possibility that transcripts and other records may later be used in a criminal investigation.

Particularly problematic, say Bibas and Rudovsky, are aspects of the university policy that, among other things, define assault as a sexual liaison in which a person is unable to consent because of drug or alcohol intake. The policy gives no concrete explanation of how to measure or define such incapacitation. Given the low standards of proof, they say there is great potential for unjust results.

In October, 28 members of the Harvard University Law School faculty signed a letter decrying the university's sexual-assault policy and investigative procedures, which they said were "overwhelmingly stacked against the accused."