From chaos to calm at one North Philly elementary school

Kenderton illustrates much about the challenges and promise of urban education, and what the shifting sands of school reform can mean to a neighborhood. A back-to-basics approach has shown early promise.

Kenderton Elementary was in full-blown crisis at the beginning of last school year: There were frequent fights, students roaming the school, walking out of the building. Teachers quit, and parents said they feared for their children's safety and worried they weren't learning much.

"It was just bad," said Aliyah Alexander, who was in fifth grade at the time. "Students weren't listening, they were running the hallways, having attitude, slamming doors, ripping stuff down."

These days, Kenderton is on the rise, thanks to a back-to-basics approach — consistency, a proven principal, and a host of investments and extra supports provided by the Philadelphia School District.

Kenderton illustrates much about the challenges and promise of urban education, and what the shifting sands of school reform can mean to a neighborhood: The school at 15th and Ontario has been frequently tagged in Philadelphia school-reform efforts that have not panned out.

For nearly two decades, periodic upheaval has been the norm for the school. In the early 2000s, the district gave Kenderton to Edison, a for-profit education company, to run. That relationship did not last; eventually the struggling school was given to Scholar Academies, a charter company, to administer.

But the charter company abruptly abandoned Kenderton in June 2016, citing the high cost of educating its large special-education population.

Such a business transaction is always a possibility when the district relies on outside companies to educate its students — Scholar Academies had the contractual right to leave, but that left the school system with less than three months to hire staff, get curriculum in order, and deal with student records and registration.

In September 2016, a staff of mostly new educators and administrators reopened Kenderton as a district school.

Linda Stevens-Whiteside watched it happen. Stevens-Whiteside grew up blocks from the school, graduated from it, then taught science there until her retirement in 2011. She remained in the neighborhood and sat on the School Advisory Council directed in 2013 to choose a charter company to run Kenderton, where more than three-quarters of students live below the poverty line and many have complex learning and emotional needs.

When Scholar Academies left, "no one was prepared," said Stevens-Whiteside. "When the children came back to school, they had no one to fall back on, no familiar faces. We had a lot of turmoil." (The staff members who had worked for the charter company were invited to stay at Kenderton, but few opted to return when the school reopened under district control.)

Stevens-Whiteside is back at Kenderton as a long-term substitute: science last year, math this year. She can put a date on when things began to change: Nov. 1, 2016, when R. Victoria Pressley came to the school.

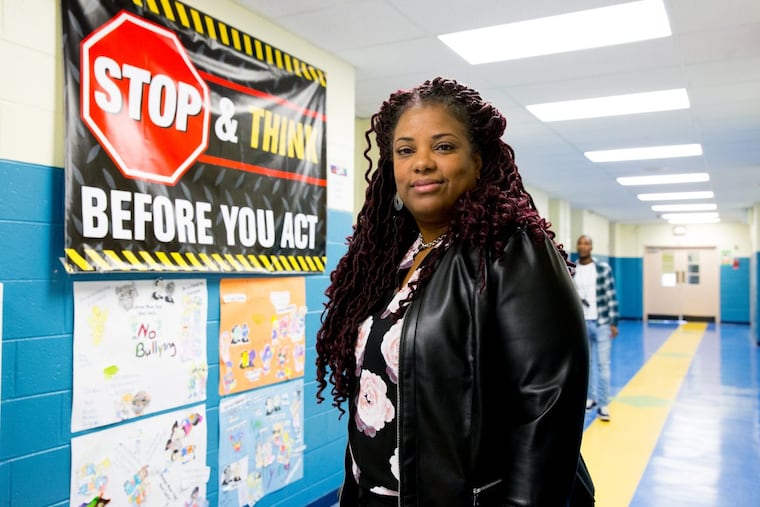

Pressley is a no-nonsense veteran: a product of North Philadelphia schools herself, an acclaimed school leader who also worked as an assistant superintendent and curriculum director. When district leaders removed the Kenderton principal who started the 2016-17 year, they turned to Pressley to restore order.

"I've always been one who liked challenges," Pressley said on a recent day, pausing from classroom observations to walk visitors through the school's blue-and-yellow hallways.

Before she started at Kenderton, Pressley parked her car on multiple days and just watched how the school operated at the beginning of the day and at dismissal.

"What I saw was chaos," she said. "And if you start the day with chaos, you're going to end it with chaos."

Pressley got quickly to work, putting new rules and systems in place. There was a staff deployment plan to make sure every area of the building had someone covering it. If children acted up, their parents had to come to school to address it; if they ripped down a bulletin board, they were given a stapler and told to reconstruct it.

"The kids just needed the consistency," said Keith Freeman, a Kenderton special-education teacher for five years, one of a few educators who have remained at the school through its various incarnations. "They can tell whether you're real or not."

Because of Kenderton's unique circumstances and the turmoil of last year, the school of 465 students in grades K-8 also got a host of supports not available to every school — and it has kept them. Kenderton has an assistant principal, a school police officer, a school psychologist, six climate workers, two counselors, and a cohort of classroom assistants. It has the luxury of small class sizes, with no more than 20 students in grades K-3.

Ralph Burnley, a respected retired district administrator, works at the school two days a week to cultivate partnerships. Kenderton children can now walk a few blocks to Temple University's medical school, where they work with students. There is a renewed relationship with Zion Baptist Church, which pays for one-on-one reading help for struggling students in the early grades, and a new connection with Dobbins High School, where children learn about film and media. There are after-school clubs and electives for middle-school students.

Kenderton still has miles to go — just 2 percent of students scored proficient on state math exams last year, and 13 percent met standards in reading.

But it is headed in the right direction.

Parents were one key constituency Pressley has had to work to win over; a core group that spent hours in the school's family-engagement room clashed with her last year. ("They used to run the building," the principal said.) Part of that parent group, which publicly complained about Kenderton's conditions before Pressley arrived, was even escorted out of the school by police at one point last year.

Shereda Cromwell, one of that group, thought of pulling her children from the school. She still has worries — about teacher turnover, mainly — but she also admits progress.

"Things are a complete 180 [degrees] from where they were last year," Cromwell said. "Last year, I felt like I had to be there every day, because at any moment, something could happen to my children. That worry is gone now."

Joyce Wilkerson joined the School Reform Commission in part because of Kenderton. Wilkerson, an administrator at Temple, read an Inquirer and Daily News story about its challenges and felt compelled to help overcome them, she said in a recent interview.

Last month, she was gratified to see Pressley's leadership — and the investments the district has made at Kenderton — paying off.

"We went around to classroom after classroom, and saw education like we expect it to be everywhere in the district," Wilkerson said. "This is what we're trying to do in all our schools."

Now, hope that it lasts, said James "Torch" Lytle, a University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education professor and former district administrator, who has written extensively about urban school reform. As Philadelphia's history shows, educational progress can be swept away by administrators eager to put their stamp on things.

"If Kenderton can be given a three-year time frame to really see how this emergent set of reforms works, then that will be key," Lytle said.

For now, neighbors are cautiously optimistic, said Stevenson-Whitehead, the retired Kenderton teacher.

"They've noticed the changes; we all have," she said. "There are so many programs and activities now. The children want to stay here."

About Kenderton Elementary School

Address:1500 W. Ontario St., Philadelphia

Principal: R. Victoria Pressley

Enrollment: 450 students in grades K-8

Percent of students who are economically disadvantaged: 76 percent

Percent of students who require special-education services: 17 percent