Parents whose children died take collective aim at hazing

Parents from around the country who lost children to hazing and alleged hazing will hold an inaugural meeting to talk about how they can work together to make change.

They found Debbie Smith's son in the squalid, cold basement of a rogue fraternity house at California State University at Chico. He wasn't breathing, and by the time he arrived at the hospital, he had gone into cardiac arrest.

"Matt's not going to make it," the hospital social worker told her.

In an instant, her happy family of four had become a grief-stricken family of three. Smith let out a blood-curdling scream, "like my entire insides came out," she recalled.

In the weeks that followed, she would learn the horrifying details of Matthew Carrington's death during a hazing ritual.

That was 2005.

Since then, Smith has been making documentaries, speaking to every audience that would listen, getting laws changed, and launching a nonprofit aimed at educating children and parents about hazing's dangers. She's had help from the most unlikely of allies — one of the fraternity brothers convicted in her son's death and the former president of the college where her son went.

Later this month, she'll get a new set of partners: other parents who have lost children to confirmed or alleged hazing over the last two decades, all of them young men and most of their deaths involving fraternities.

In an inaugural meeting, parents from California, Louisiana, New Jersey, Texas, and other spots around the country — representing a minimum of 15 children who have died — will meet in South Carolina for two days to discuss how their children died and what can be done to protect others from the dangers of hazing.

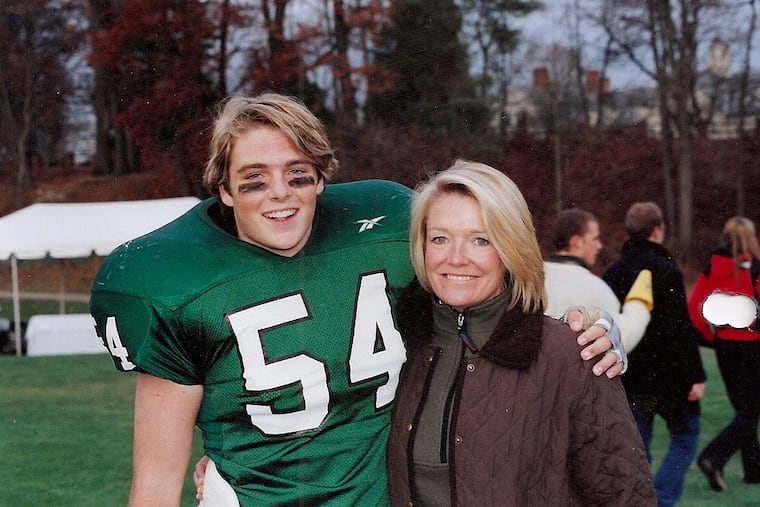

"It puts a bigger face on the story," said Leslie Lanahan, whose son, Gordie Bailey Jr., the captain of his high school football team, died after an alcohol-saturated fraternity event in 2004 at the University of Colorado at Boulder. "I don't think it has ever gotten the attention it deserves collectively."

Hazing has been a problem for decades. In a national 2008 study of more than 11,000 college students, 55 percent of those involved in clubs, teams, and organizations said they experienced hazing. Dozens of students have died, including four in 2017.

But the fledgling network has one tool grieving parents like Lanahan did not: a more interconnected world that so effortlessly brings together advocates. Some of the attendees at next month's inaugural conference met on Facebook, where they first conceived of a meeting. They've even set up a hashtag, #ParentsUnite2StopHazing.

The group plans to strategize on how to accomplish several key goals, including getting better educational programming on hazing in middle and high schools, strengthening state and federal laws on hazing, and changing the culture on college campuses, said Smith, a San Francisco Bay area resident, who uses the initials "MM" after her name for "Matt's mom." The parents have invited anti-hazing advocates and college student affairs administrators to speak. There are no plans to raise money, but that could change once a platform is developed, Smith said.

Cindy Hipps, whose son Tucker died in 2014 while on a group run with members of a fraternity he was pledging at Clemson University, first suggested and will help host the meeting in the town where she lives. The family has maintained that hazing led to her son's fatal fall while on the run.

Other parents who have been working independently for change plan to attend, including California couple Gary and Julie DeVercelly, whose son Gary Jr., a student at Rider University in New Jersey, died in 2007, and who have been pushing for federal legislation on hazing.

For others, the loss is more fresh. Jim and Evelyn Piazza, parents of Tim Piazza, who succumbed a year ago Sunday to injuries after a booze-fueled fraternity party at Pennsylvania State University, also expect to be there.

So do Stephen and Rae Ann Gruver, whose loss is even fresher: Their son Maxwell, a student at Louisiana State University, died in September.

While planning the meeting, Lanahan began to realize other parents have been working independently to effect change.

"I didn't know some of these people were doing the same things," she said. "We can work together and be a little bit of a louder voice."

While fraternity members charged in her son's death were found guilty of giving alcohol to a minor, she said, the family did get a financial settlement from the fraternity and several of its members, which was used to start the Gordie Foundation. The fraternity as part of the settlement acknowledged her son was hazed. The foundation has since become the Gordie Center at the University of Virginia and does outreach to youth on hazing and alcohol poisoning, she said.

"We're really proud that Gordie's name continues," said Lanahan, of Dallas.

The family also in 2008 produced a documentary, Haze.

Lanahan and Smith said consequences for hazing have to be stiffer and law enforcement has to take a tough stand. Schools also must offer anti-hazing education, they said.

"When you talk to 1,000 kids in an auditorium, that's just 1,000," Smith said. "And there are millions we need to reach."

Her son's death followed three nights of fraternity "Hell Week," when he had to perform calisthenics in a frigid basement with raw sewage on the floor and a fan blowing cold air on him. Then he had to stand on one foot and answer questions, all while being told to drink copious amounts of water.

Even when he had a seizure, no one called for help, she said.

He died of water intoxication. The excess water caused a deadly imbalance in his electrolytes and caused his brain and lungs to swell.

Smith's work to prevent other deaths has been relentless. She's helped produce documentaries for other countries; in one, her voice was dubbed over in French.

"You are just never done," she said. "You've got to get justice. You want to make a difference."

California adopted "Matt's law," which made hazing a felony in cases where death or serious injury occur. In 2015, on the 10th anniversary of her son's death, she launched AHA! (Anti-Hazing Awareness) movement. Paul Zingg, who led the university where her son died until 2016, sits on its board.

Some of the most effective voices in support have been fraternity members sentenced in her son's death, she said. Jerry Lim, who served four months for accessory to a felony and hazing, has been a speaking partner.

At first, Lim said, he helped because it was part of his required community service. When the requirement ended, his commitment continued.

"It's a feeling of obligation," said Lim, a law clerk from Stockton, Calif., who is in line to become a lawyer. "No matter what my personal part was, I still feel bad."

Lim, "pledge general" of the fraternity, had advocated easing up on the pledges, Smith said, but others overruled him. Lim said at the time, he didn't know the danger Carrington was in. He had gone through the same hazing the semester before. The thinking, he recalled, was that "the things we are given in life we don't value near as much as the things we earn."

In retrospect, he said, hazing should be eradicated. When something seemingly as innocuous as water can kill, no ritual is safe, he said.

"It only takes one activity that you thought was harmless before someone gets hurt," Lim said, "and kids aren't in a position to decide what is and isn't a healthy activity."

Parents who have lost children to hazing and are interested can contact Smith at lovesfmlb@aol.com