It takes a long time to close a charter school in Philly. Here’s why

The decision to close a charter school in Philadelphia is drawn out by state law as well as local resistance: "There's a lot of momentum behind a school once it's open."

Standardized test scores at Charter High School for Architecture and Design dropped during the last four years. For the most part, it compared unfavorably to schools with similar student populations and to the Philadelphia School District. Attendance declined. The School Reform Commission, before it went out of existence, recently voted against a five-year renewal for the school's charter.

But that doesn't mean it's shutting down — or ever will.

It can take years to close a charter school in Philadelphia, a decision drawn out by state law and local resistance.

Three charter schools recommended for nonrenewal by the School District in 2016 and another three for nonrenewal or revocation in 2017 remain open, with no closing dates imminent. The charter for one of those schools, Aspira-run John B. Stetson, expired even earlier, in 2015.

At the SRC's final meeting on June 21, it renewed two charters that the district had previously advised it to close. The outgoing head of the district's Charter Schools Office, DawnLynne Kacer, said both schools agreed to surrender their charters if they didn't meet certain conditions at the end of their terms — three years in the future for one, and four years for the other.

The end result could be the same, Kacer said, because "that's probably the amount of time it would take" for them to close anyway.

As charter schools have grown in Philadelphia, educating about 70,000, or one-third, of the city's public-school students in 84 brick-and-mortar schools, the prolonged process for closing means "we are really putting kids in continuously detrimental situations," said Amy Ruck Kagan of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers.

Ruck Kagan, a former director of a Philadelphia charter group, noted that the decision on whether to close a school becomes more complicated the longer it stays open, because the school has time to make changes: replacing the principal, for instance, or hiring a high-powered attorney.

For charter schools, "the biggest issue" with the nonrenewal process "is that it creates uncertainty. Uncertainty for parents, uncertainty for staff, uncertainty for the entire school organization," said Larry Jones, a former president of the Pennsylvania Coalition for Public Charter Schools and the CEO of Richard Allen Preparatory Charter School in Philadelphia. The SRC issued a notice of nonrenewal to Richard Allen in October; Jones said a hearing will be held this fall.

In other states, "you see a process that's much more transparent, much more consistent," Jones said.

While it's similarly difficult to close charter schools in some other states, Ruck Kagan said, others have laws that promote closure of poor performers.

In New Jersey — where Ruck Kagan previously led the state's charter office — state regulations lay out a time frame for renewal decisions. Unlike in Pennsylvania, where local school districts authorize charters, the New Jersey Department of Education is the lone authorizer. It must notify charter schools of renewal decisions by Feb. 1 in the last year of their charter terms; school leaders must then quickly implement any closure plan.

As in Pennsylvania, New Jersey charter schools have the right to appeal. And they can ask a court to stay a closure decision. But a New Jersey court has never granted a request for a stay, Ruck Kagan said.

In Pennsylvania, the law spelling out standards for charter schools "doesn't have a lot of teeth," said Joe Dworetzky, who served on the SRC from 2009 through 2014.

And the nonrenewal process is far lengthier. A local school board must issue a notice of nonrenewal to a charter school; in Philadelphia, this had occurred through an SRC vote after the School District made a recommendation.

Then a hearing must be scheduled — and it can be extensive. One for Eastern Academy Charter School in Philadelphia, for instance, spanned 14 days this past October through December.

After a public comment period, the school board must again take action to nonrenew or revoke the school's charter. The charter school can then appeal to a state board — all while continuing to operate.

Pending before the state Charter Appeals Board is an appeal from Philadelphia's Khepera Charter School, which had its charter revoked by the SRC in December. The Charter Schools Office doesn't have any recent reports of payroll issues at Khepera, which ended the 2016-17 school year early due to financial troubles. But a district spokesman said the school had not yet submitted its most recent audit, which was due Dec. 31.

Eastern Academy, which the SRC voted to nonrenew in April, is also fighting closure. A spokeswoman said an appeal to the state board was mailed last week — though there wasn't a clear deadline to do so. "We don't see a hard time frame" in the state charter law, said lawyer David Annecharico. He said the school, which says it was unfairly evaluated by the district, felt during its hearings that it was "highly likely" it would be preparing for an appeal.

Philadelphia School District officials also assess the possibility of an appeal in deciding whether to recommend nonrenewal of a charter — and what changes a school might be able to make in the time it takes to get to the appeals board.

"What could a school reasonably do in two years? Our office tries to play that scenario out," said Kacer, who is stepping down from the charter office Monday. If a school that isn't meeting standards could improve, the office sometimes proposes renewal with conditions, rather than moving to close the school.

It took that route recently with two schools that didn't measure up on its evaluations. While Universal Alcorn and Universal Institute approached the charter office's standards in academics and organizational compliance, both failed to meet financial standards.

In the case of Universal Alcorn — an elementary and middle school in Grays Ferry formerly run by the district — the office's evaluation notes that the school "has suffered a substantial operating loss and has a deficiency in net assets. This creates an uncertainty about the charter school's ability to continue as a going concern."

With "internal controls" and cash-management strategies, the Universal schools — run by music legend Kenny Gamble's company — could improve, Kacer said. Her office also recommended renewal with conditions for a third Universal-run school, Vare Promise Neighborhood Partnership, after previously advising it not be renewed. The SRC earlier this year directed Kacer's office to negotiate with Vare.

Bill Green, who was appointed to the SRC in 2014, said the commission used negotiations to its advantage, though he acknowledged it hadn't always obtained its desired result. Green had pushed to delay votes for the Aspira-run Olney and Stetson charter schools, recommended for nonrenewal in 2016.

Despite the added time for Aspira — whose management of five charter schools drew scrutiny from the state auditor — the SRC voted in December against renewing the schools. "We probably waited too long, in hindsight," Green said.

The challenge with closing a school once it's "up and running … it's a business," with employees, students, and neighborhood presence, said Dworetzky, the former SRC member. "There's a lot of momentum behind a school once it's open."

“As much as people complain about the quality of individual public schools, when it’s the schools they go to or their kids go to, they come out and they tell you how hard it is for them,” Dworetzky said. “You can’t just brush that away.”

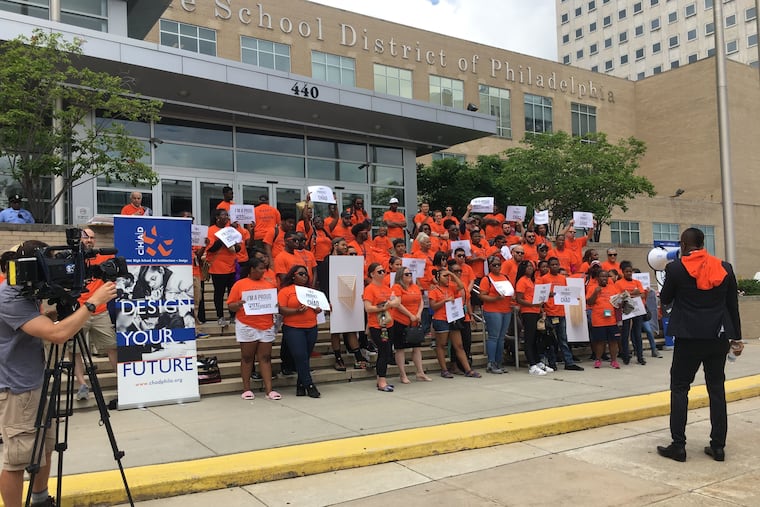

Before the final SRC meeting, supporters of CHAD, the architecture and design school facing nonrenewal, rallied on the steps of School District headquarters. Wearing orange T-shirts that read "CHADvocate," they chanted in response to an activist's prompts, amplified by megaphone.

"This is not the end," the activist, Sixx King, a director and actor whose presence was arranged by a public relations consultant, told the crowd. "This is the beginning."