These Philly schoolkids marched against injustice 50 years ago, and police responded with nightsticks. Today, they inspire a new generation

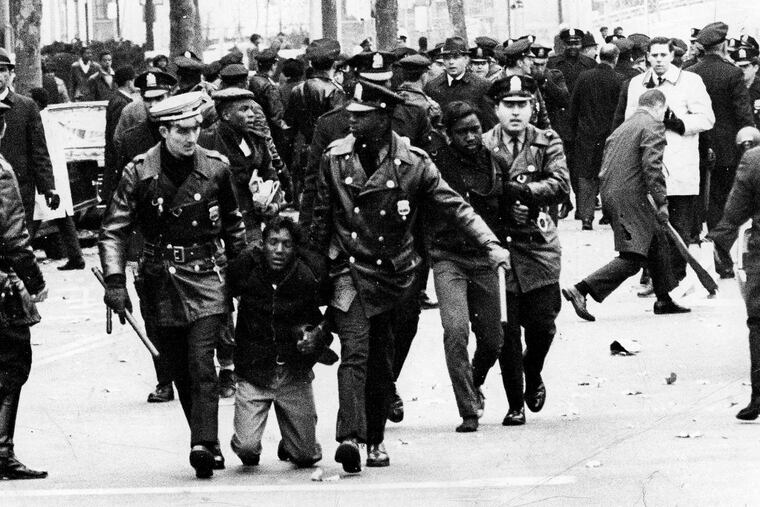

"The clubs were going in every direction," said an adult organizer of the walkout to bring reforms and more awareness of black students' concerns. Then-Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo ordered more than 100 men in full riot gear to charge students who had been largely peaceful. "The kids were helpless."

Walter Palmer remembers Nov. 17, 1967 as if it were yesterday — cool, cloudy, and joyous, at first.

After a year of careful preparations, more than 3,000 Philadelphia public school students poured out of their classrooms and converged on the old Board of Education building at 21st Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway to protest conditions for black students. They came with a list of 25 suggested changes and requests, from the infusion of black history into the curriculum to the right to wear their hair in Afros.

By then, black students comprised a majority of the public school population, yet black people were largely absent from decision-making roles. Across the country, the civil-rights movement continued to reverberate, and in Philadelphia, many students were eager to join.

Inside the school-board building, youth leaders met with the superintendent and board president. Outside, teenagers and supporters kept marching, chanting, greeting their friends.

A newspaper account at the time described the atmosphere early that day as more like a "picnic" than a demonstration. And then, at Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo's direction, more than 100 officers in full riot gear swarmed on the scene. Nightsticks drawn, they waded into the crowd, swinging at the students. Police dogs were released.

"The clubs were going in every direction," said Palmer, an adult organizer then and now an 83-year-old teacher at the University of Pennsylvania. "The kids were helpless."

Forty-two students and 15 adults were arrested, and dozens were injured, some seriously, drawing a national spotlight. The day became a defining moment not just in the legacy of Rizzo, who went on to become mayor, but also for the school system and its students. Though some would not sprout for decades, seeds of change were planted that day.

Matthew Countryman, a University of Michigan history professor, calls the 1967 Philadelphia walkout a seminal moment for the city, a catalyst for the creation of black studies programs at universities throughout the U.S. and a driver for looking at school integration not just in terms of student demographics, but also curriculum and culture.

"There was real potential in that moment," said Countryman, the author of Up South, an account of Philadelphia's civil rights and black power movement. "The officials of the school system were really ready to figure out, with black students, black parents, black teachers: 'How do we do this right? How do we create a responsive school system?'"

In the immediate aftermath of the walkout, school administrators in Philadelphia began work to incorporate African American history into the curriculum. It would not be until 2005 that the district would require all students to take a course in the subject, becoming the first public school system in the U.S. to do so.

But 50 years later, the actions of Nov. 17, 1967 still resonate.

Education activists today say their work is informed by that walkout. Palmer and others who marched that day were just honored by City Council. A panel discussion is planned for Friday night at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. A commemorative teach-in is scheduled for Saturday. There is also a push to place a historical marker at the site of the demonstration.

Juanita Miller, an organizer for the Philadelphia Student Union, a citywide youth activism group, said she and the teenagers she works with draw inspiration from the walkout as they organize to fight against school closings, for safe schools, and for local control of the district, scoring with activists around the city a major victory with the School Reform Commission's recent vote to dissolve itself.

That day a half-century ago, Miller said, "ties to the work we do today."

Seeking to evict ‘a white-dominated school system’

They had organized for more than a year.

The first stirrings came from youth members of the Black People's Unity Movement, frustrated by a lack of student voice inside public schools. They wanted more black teachers and administrators, more union apprenticeship opportunities for black students, more attention paid to the fact that black students dropped out of school at a rate three times higher than their white counterparts.

They wanted black student groups recognized as legitimate school organizations. They wanted to be able to refuse to salute the U.S. flag without penalty.

And, recalls Palmer, who was active within that group, they wanted to openly embrace their African roots.

"They wanted to wear their hair natural; they wanted to wear African dashikis and kufis. They were told, 'No, you can't wear that.' They were told they couldn't go by African names," said Palmer, who went on to found a charter school named in his honor, which closed in 2014.

The students organized in face-to-face meetings. Point people at every school mimeographed flyers and handed them to friends. One read: "If the Philadelphia school system defeats your child now, he will remain defeated for the rest of his life…Give the white-dominated school system an eviction from the black community."

With the help of Palmer and other adults, the students drafted their bill of rights. They had an action plan, and a date: Nov. 17, a Friday. Palmer remembers the group wanted to strike before Thanksgiving.

Things were quiet, at first, that day. Palmer and some other adults were in place early outside the education board building, and plainclothes police wondered if the event would even materialize.

By 10 a.m., though, students were streaming from their schools and heading to the site. At Bok, a vocational high school in South Philadelphia, a student pulled a fire alarm to create a diversion to allow people to walk out; at other places, young people just left. Some walked to Center City; others took buses.

The crowd swelled steadily, high-spirited but calm. A group of negotiators — mostly students, with a handful of adults — were chosen to meet inside with Superintendent Mark Shedd and School Board President Richardson Dilworth.

VIDEO: KYW-TV / Temple University Libraries

At one point, one of the negotiators called out of a window: Shedd and Dilworth had agreed to all of their demands but one. Later, they hollered again: The officials had agreed to the last demand!

But just after noon, things turned. Police seemed uncomfortable with the growing crowd, which Palmer said the city and law enforcement did not anticipate. Rizzo, who had just attended a swearing-in ceremony for 111 new police sergeants, ordered the officers onto two police buses bound for the district building.

According to accounts of the time, Rizzo received reports that the demonstration was growing unruly, with students banging on parked cars. Soon after he and the buses arrived on the scene, the police commissioner told his officers to quell the students. By some accounts, Rizzo ordered officers to "get their black asses" — a line that would loom large in his controversial, complicated political legacy.

VIDEO: KYW-TV / Temple University Libraries

David Hardy, then a 16-year-old junior at Olney High, arrived late to the protest. He recalls approaching the school board building when he saw the officers swarm.

"Police cars were red back then, and they had a red police bus that pulls up with all these cops with helmets and billy clubs, and they started whaling on kids," said Hardy, the now-retired founder of Boys' Latin of Philadelphia Charter School. "It was ugly."

Karen Asper Jordan, a city schools graduate who came to the rally, said she heard Rizzo say "get their asses," but not "black asses." She also heard a city official implore Rizzo to exercise caution with the protesters because they were children.

Still, she was thrown onto the ground by a police officer, then dragged through the street. A man tried to help her, and police targeted him, too.

"They were dragging me, and they were beating him with a blackjack," Jordan said. "I remember covering my face to stop being struck in my face."

Eric Ward, then the student body president at Vaux Junior High and an organizer of junior-high students for the walkout, watched as officers unleashed snarling dogs on the students.

"That was the first time I had ever witnessed something like that," said Ward, who had walked a mile and a half from Vaux, at 23rd and Master streets. "I was very scared and intimidated; we all were. I will never forget that day."

The Rev. E. Marshall Bevins, an Episcopal priest, said he saw three officers beating a young girl on the ground. He implored them to stop, he told the Inquirer soon after the incident.

"I was shoved from behind and suddenly, I was hauled away," Bevins said then.

He was among the 57 arrested, as were Palmer and Jordan, who was left bleeding after being dragged by the officer. Dozens more were injured, some seriously.

That it erupted was not such a surprise, given the extraordinary upheaval nationwide. Philadelphia had already seen a race riot in 1964; police in other cities were regularly clashing, sometimes violently, with civil rights protesters.

"The police were responding to everything that was going on around the country," Hardy said. "They were scared. But they were treating us like we were these armed, grown men coming down there to tear up downtown — and we were kids. It was an overreaction to what was happening."

Change arrives, but slowly

Reactions to the walkout — described by some as a "police riot" — were mixed.

"The mere display of brute force, with 300-400 armed police encircling youngsters — easily excited schoolchildren — will in itself cause the explosion that occurred Friday afternoon," Common Pleas Court Judge Raymond Pace Alexander said the next day at a bail hearing for some of the people arrested at the protest.

Mayor James Tate and others staunchly defended Rizzo, who said his actions against the students were warranted.

VIDEO: KYW-TV / Temple University Libraries

Many others were aghast. There were calls for reforms and, later, lawsuits.

Shedd, a progressive, took seriously the issues that prompted the walkout, and going forward.

"One of the biggest problems confronting us as white people is the tremendous mistrust on the part of Negroes, resulting from generations of unfulfilled promises," the superintendent said at the time.

Soon after the walkout, Shedd convened a committee to infuse African and African American history into the curriculum, with experts helping to write model materials. But much of that work was halted when Shedd departed after Rizzo's 1971 election as mayor; in his campaign, Rizzo had promised to rid the city of the superintendent.

In the decades since, there has been little in the way of formal remembrances of that day. But when African American history became a mandated course for Philadelphia public school students in 2005, officials drew a straight line from that policy — the first of its kind in the U.S. — to the actions of 1967.

On Thursday, Palmer, Jordan, Ward, and others who demonstrated that day stood beaming in City Council chambers as Councilwoman Helen Gym read a proclamation honoring their actions.

Gym, whose political career was preceded by years of activism, said the issues that fueled the 1967 walkout feel very modern in some ways — concerns over community control of schools, young people's voice, matters of race.

"We want to honor not just what happened 50 years ago, but to recognize that student activists from then until today have been very present in the effort for racial and educational justice," said Gym.

Palmer thinks there ought to be a historical marker at the old school-board building, letting people who walk by the site, now a condominium complex, know what happened there.

It's time, said Palmer.

"We ought to remember," he said.