Temple confronts student opioid deaths

Two students died within a week earlier this semester. Before that, there were two others who few knew about.

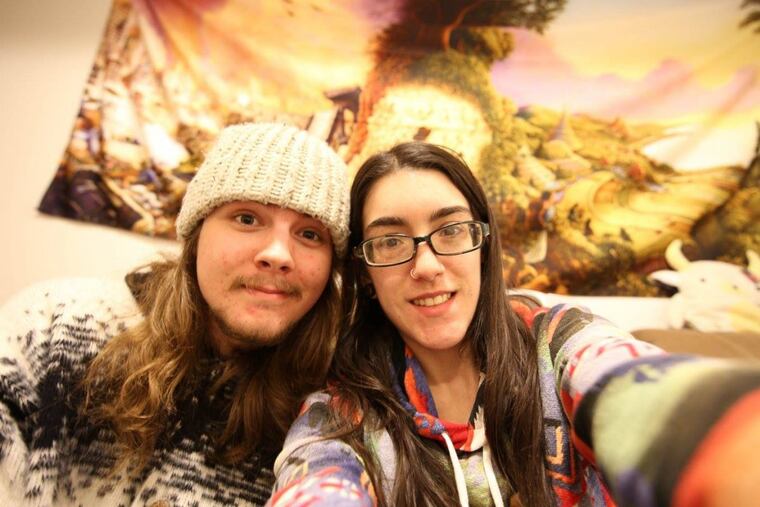

Gabrielle Greco and Ben Molander became fast friends when they met as students at Temple University in 2015.

Greco, 23, of Huntingdon Valley, was excited to study Japanese and dreamed of a semester abroad in the country whose culture, books, art and language she loved. Molander, 21, of York County, was less sure what he wanted to study, but started as an engineering major and loved computers.

"They became inseparable," Greco's mother, Melissa, said.

Neither made it to graduation.

Greco died last April in her apartment of a heroin overdose. Molander spoke at her funeral.

Then on Sept. 21, he died. Also heroin.

Most staff and students at Temple didn't know. Both died off campus. Molander had dropped out in 2016 and Greco withdrew in February, the same month she overdosed the first time.

With the opioid epidemic ravaging communities around the country, including battered pockets of Philadelphia not far from Temple, their deaths highlight a stark reality for colleges: Much attention is given to overdoses by current or on-campus students, but no one tracks how many more onetime promising students waste away in a gradual, hidden drug spiral.

"Our students are dying or disappearing and very easily could be dying," said Jillian Bauer-Reese, a Temple assistant professor of journalism who is in recovery and who has for years believed the university needs to do more to help students struggling with addiction. "I mean you send your student to a school and hope that the school has the resources in place to take care of them. I think the question is do we not have those resources to care for students who are in dire need?"

Bauer-Reese's concerns have been echoed this month by other Temple faculty and students as the North Philadelphia campus reels from two student overdose deaths within a week, one of them succumbing in the heart of campus.

Michael Paytas, 24, a senior marketing major from Ridley Township, was found unconscious in a restroom at the Paley library on Nov. 27 and later pronounced dead. Five days later, James Orlando. 20, of Reading, died of an overdose in his off-campus apartment.

"No one is safe," senior Andrew Castle, 21, of Long Island wrote on a Temple Facebook page, drawing hundreds of "likes" and comments. "I hope Temple University will begin to do its part in confronting the problem and that the conversation is brought to the table."

Nationally, colleges are struggling with the impact of the opioid crisis; some are stepping up more than others.

Rutgers, Texas Tech University, and Augsburg University in Minnesota are among the most advanced, while Penn State and the University of Southern Maine's Portland campus also offer robust programs, said Tim Rabolt, of the Association of Recovery in Higher Education. At Portland, there's a close-knit peer recovery community, yoga-based recovery classes, coaches and weekly meetings.

"The trouble is universities are a little hesitant to get into areas they might not feel the best equipped to deal with, so when it comes to students battling more than just binge drinking … they kind of feel it's best to be handled off campus," Rabolt said.

Rutgers offers a recovery residence hall with a recovery counselor, organized group activities and easy access to counseling, health and other services. Nearly 30 students live in the house, but close to 60 are involved in the recovery community at Rutgers.

Bauer-Reese and others at Temple say the university should offer recovery housing, similar to Rutgers, as well as recovery counselors, daily support group meetings and a staff person who would serve as their advocate. They also call for more awareness of the help that is available.

Still, Temple is doing better than some of the other schools in Philadelphia, said Devin Reaves, executive director of Life of Purpose, a recovery program in Cherry Hill. Temple, Reaves noted, has several addiction specialists on staff. Some schools, he said, have none. Temple is also one of the few colleges with a psychiatrist who prescribes suboxone, a drug for opioid addiction.

"All universities need to be more proactive with outreach to make sure students know there is a counseling center and services are available," he said. "When your campus is in the heart of North Philadelphia, drugs are very easy to get, so recovery needs to be easy to get."

Members of Temple's student government, as a result of Paytas' and Orlando's deaths, called for students to be instructed in the use of Narcan, a drug that can save someone overdosing on heroin. Temple police are trained to administer it.

"It should be as ubiquitous as a first aid kit," said Jerry Stahler, a Temple professor who teaches a course called "Drugs in Urban Society" and who served on the mayor's task force on opioids.

Temple officials say they are considering the suggestions but that they are not experiencing an uptick in students being hospitalized for drug treatment, seeking help for it at the counseling center or being cited for possession.

Temple is aware of four students who died of overdoses during the 2016-17 year, including Greco, according to Stephanie Ives, associate vice president and dean of students. For the first half of this year, there were two, not including Molander. Four students are in treatment for opioid addiction this semester, compared with 10 to 12 in prior years.

Temple, Ives said, is always looking to improve, particularly in helping to train students to intervene when peers are in trouble.

"We are not with our students overnight or on weekends," she said. "It's important to influence the student culture."

The university, she said, also has a team that responds to students in crisis and anyone concerned about a student can send a message.

Castle, a sociology major, said Temple must publicly recognize its position in a city with such a major drug problem. The loss of a student in the library, surrounded by peers, underscored that need.

"The fact that it happened in such a normal setting freaked everybody out," he said. "I was in the library that night."

At Temple, as well as other campuses, complaints have surfaced that students must wait too long – weeks – before they can get an appointment at the counseling center. Those complaints intensified after the deaths. Temple, officials said, has increased counseling staff in the last few years. Students in urgent need are provided counseling within two days.

Bauer-Reese, 34, who said she drank excessively as a Temple student, went into recovery five years ago. She tells students the first day of class and notes it on her syllabus so students know they can reach out — and they have. Earlier this year, she got an email from a freshman who didn't know where on campus to get help.

She connected him with the Temple University Collegiate Recovery Program, a recently started student group for which she is the adviser.

But more recovery resources are needed, Bauer-Reese said.

"I just see this as an opportunity for us to lead the way in Philadelphia," she said.

For parents, it's frustrating and heartbreaking.

"I don't blame the university for what happened, but I do think they need to play a part in the solution," said Sue Crathern, whose son quit Temple in 2015, 18 credits shy of graduation, as he fought heroin addiction.

While she said she has met a handful of other parents of Temple students struggling with addiction, she didn't know of any whose child had died until this month.

"It made me feel guilty that I'm not doing enough," said Crathern, a research chemist from Oreland. "It's like Russian roulette. How much more has to happen before Temple will acknowledge this?"

Her son is back in college, in North Carolina now. She never told Temple about his addiction; she didn't know whom to call. But she wants the university to know now.

So does Melissa Greco.

"There needs to be more conversation about it," Greco said. "Neither the police or Temple acknowledged her overdose. It was so surreal. It was like nothing happened. … Hopefully, more will be done at the college level, before more young adults die."

(Ives said Temple knew of Greco's death and provided support to staff and students who were grieving, but did not issue a campus-wide announcement. Temple was not aware of Molander's death.)

Greco's daughter had a history of depression and anxiety. But she said her first two years at Temple went well and she ended the 2015-16 year with decent grades. In fall 2016, she went off her depression medication. It was around that time she began to use heroin, she would later tell her mom.

She began to struggle in school, even getting a D in one of her Japanese courses. But it wasn't until she overdosed for the first time last Valentine's Day that Greco learned about the heroin.

"The nurse showed me her track marks," she said. "I still didn't believe it, until I went to her apartment and found syringes and bags of empty heroin."

Greco works as a detox nurse, helping others with addiction, and is a recovering addict herself.

"Yet as a parent, I was blind-sided," she said.

Greco got her daughter into treatment. But on April 13, she overdosed again in her apartment, two blocks from Temple and near a police substation.

Molander, her daughter's best friend, was devastated. At the funeral, his mother, Lori, asked if he had used heroin: "Mom, you know I wouldn't do that," he told her.

He had dropped out of Temple the prior year but was living in Philadelphia.

When he visited in August, Lori Molander said she noticed he was thin and didn't seem to be himself. He told her he was depressed and still grieving over Greco. He was hospitalized and began medication for depression. That seemed to help, said Molander, who now lives in Ohio.

Then on Sept. 21, she got a call from his roommates. They found him slumped in a corner in his room.

She doesn't blame Temple.

"It's an epidemic in our country," she said. "What we really want and desire is that kids can get help and not feel embarrassed about it. I hope through Ben's death, if one person can get help, that will at least be one good thing that came out of this."