Art | A small-scale introduction to Church

Frederic E. Church was the most acclaimed landscape painter in America during the mid-to-late 19th century. Yet his reputation didn't survive for long after his death in 1900. (The same thing happened to Thomas Eakins, who died in 1912.) The advent of modernism pretty much swept away the epic romanticism that characterized Church's most memorable pictures.

Frederic E. Church was the most acclaimed landscape painter in America during the mid-to-late 19th century. Yet his reputation didn't survive for long after his death in 1900. (The same thing happened to Thomas Eakins, who died in 1912.) The advent of modernism pretty much swept away the epic romanticism that characterized Church's most memorable pictures.

It wasn't until a half century later, when Americans began to take seriously the art history of their own country, that Church was revived. The first modern exhibition of his art was organized in 1966. In 1979, his long-lost masterpiece The Icebergs, painted in 1861 when the artist was in his prime, was purchased at auction for the Dallas Museum of Art for $2.5 million, then an astonishing price for an American work.

Today, Church's stature as the preeminent member of the so-called Hudson River School is secure. Ironically, many of his spectacular pictures depict locales outside the United States. Unlike Albert Bierstadt, who revealed the glories of the American West to domestic audiences, Church remained east of the Alleghenies when he wasn't seeking panoramic vistas in South America, the Arctic, the Near East and Jamaica.

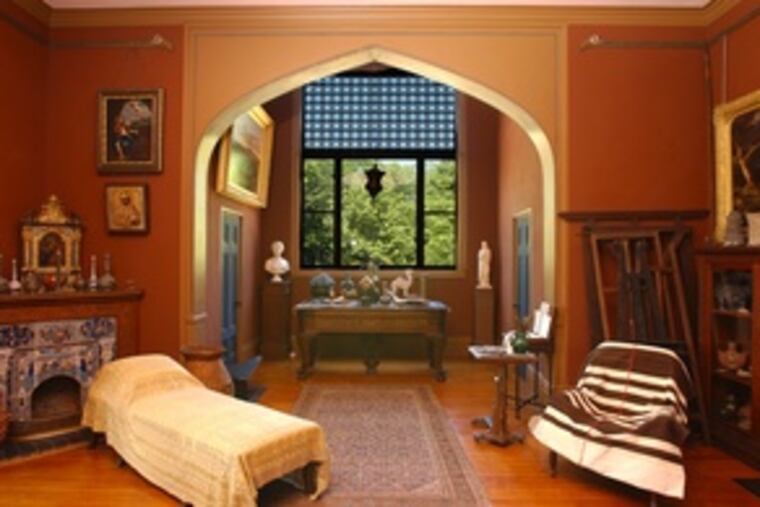

Church is remembered for one other achievement, the fairy-tale "castle" he built on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. Now a New York State historic site, Olana is an exotic time capsule filled with his furniture and the dozens of decorative objects and curiosities he collected during his travels.

In addition to an extensive archive, Olana also houses more than 100 paintings, many of them sketches or detailed studies for some of the artist's most celebrated pictures, such as Niagara, Heart of the Andes, and Twilight in the Wilderness. When Olana closed last year for a $2.2 million upgrading of mechanical systems, some of these works were packaged as a small traveling exhibition.

The Princeton University Art Museum is the final venue for "Treasures From Olana"; the house is to reopen to visitors on or about Memorial Day weekend. It's a small show, 18 pictures in two small galleries, but Church's extraordinary technique delivers a deep and rich experience.

Despite its size, "Treasures" is welcome because there is only one painting by Church in Philadelphia public collections, a view of an Ecuadoran volcano given to the Philadelphia Museum of Art three years ago.

With one exception, the paintings at Princeton are modest in size, from 11/2 to 2 feet high by between 24 and 30 inches wide. A study for Niagara, on two sheets of joined paper, is four feet wide. Most are oils on paper, some mounted on panel or canvas.

From this description one can see that the overpowering scale that impressed 19th-century audiences, and that remains a significant aspect of Church's appeal, is absent. "Treasures" presents Church almost in miniature; in these sketches and detailed preparatory studies the themes are familiar but the emotional voltage, in those pictures where it's manifest at larger scale, is turned down.

While a few pictures are obviously "sketches," most of the paintings are fully finished works, often precisely and profusely detailed. Church was an exacting technician in the manner of John Ruskin, as he demonstrates, for instance, in Tropical Vines and Trees, Jamaica. Every leaf in this tangle of dense foliage seems to be meticulously rendered.

This was painted nature just before impressionism, a razor-sharp image in which the profusion of life wasn't merely suggested but accounted for in astonishing individuality. It's not just pedantic showing-off, either; Church's gradations of light and shadow have produced a complex scene of shifting perception and luminous color.

His study for his first great achievement, Niagara, called here Horseshoe Falls, introduces the novelty of that composition, which puts the viewer right at the lip of the falls on the Canadian side. You feel as if you're about to tumble into the raging torrent. What's missing, though, is the gravitational force generated in the full-size canvas, nearly eight feet wide, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington.

Many other paintings in "Treasures" reinforce the sense of intimate communion that the artist felt with untrammeled and unadulterated nature. Mexican Forest - A Composition, a dark, horizonless glimpse into a dense copse, is almost mystical in this regard. But the show also allows us to step back and trace the arc of Church's career.

In The Catskill Creek, painted in 1845, we see the precocious youngster - he was then about 21 - starting out as a pastoralist. The juxtaposition of mirror-still waterway and distant mountain, with a farmhouse in the middle ground, is tranquil and civilized. Nature is under control here to the extent that the wooded middle ground looks like a park.

Later, Church would shift from that docile pastoralism to more fearsome representations of nature that implied power, majesty, and the ability to inspire true awe (not the trivialized teenaged "awesome" of today but an emotion that combined fear with respect). This becomes evident in The Heart of the Andes of 1858, the template for one of his largest and most compelling landscapes.

Church would become emphatically Turneresque in the painting Cotopaxi of 1862, in which an erupting Ecuadoran volcano signifies nature at her most tempestuously Wagnerian. This theme is missing from the show, but the equally florid and demonstrative Twilight, A Sketch, the model for Twilight in the Wilderness, is adequate compensation.

The show includes paintings that might be considered less typically Churchian - clouds over Olana, a variegated Vermont hillside, a German rainbow, and a snow scene. The largest painting is a dramatic view through a cleft of an ancient building at Petra, Jordan, hewed from solid rock. The artist designed the heavy gilt frame. All but four paintings are mounted in their original period frames, chosen by Church; the others are modern replicas.

"Treasures From Olana" is a handsome and edifying introduction to the artist for visitors who don't know much about him. It might inspire those who do to visit Olana, where they can see how art and life came together for this American master.

Art |

Art

Treasures From Olana

Princeton University Art Museum, through June 10

Art | Olana's Treasures

"Treasures From Olana" continues at the Princeton University Art Museum through June 10. The museum is situated in the center of the campus, next to Prospect House and Gardens. It is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays and from 1 to 5 p.m. Sundays. Free admission. Information: 609-258-3788 or www.princetonartmuseum.org.

EndText