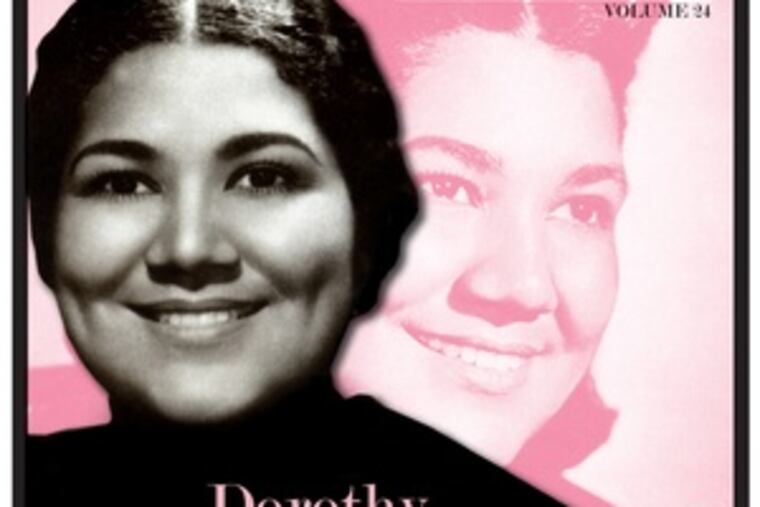

Dorothy Maynor, a radiant reprise

The transcendent voice of soprano Dorothy Maynor soars again on a new CD of a 1940 recital. Said Eugene Ormandy: "She is the greatest thing I ever heard."

Singers don't recede quietly into obscurity, even when they try. So the very fact that soprano Dorothy Maynor had to be rediscovered is confounding.

Based on a newly released recording of a 1940 recital, Dorothy Maynor in Concert at the Library of Congress, she was among the great American-born sopranos of the 20th century. Yet biographical information is sketchy and contradictory, right down to the year of her birth (some say 1909, but most sources give 1910) and place of death (indisputably West Chester, Pa., though one source says Norfolk, Va.).

At her peak, the dimpled, 4-foot-10 soprano sang concerts for audiences as large as 15,000 (at the old Convention Hall in West Philadelphia), as well as for the city's elite with the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music. Her recordings sold well. But her vocal prime fell during an era when options for African American singers didn't extend into the opera house - and besides, she had other things she wanted to do with her life, like founding and developing the Harlem School of Arts in 1964.

When she died at age 86 in 1996 after living quietly for years in Kennett Square, her only recording presence was a single (and sublime) RCA LP. Most likely, she didn't mind a bit.

The life of a touring singer hadn't appealed to her. The honor of singing at Dwight D. Eisenhower's 1953 inauguration came with the realization that she was being used to draw black voters away from the Democrats, said the Rev. Shelby Rooks, her husband of 54 years, after her death. She wasn't about to say no to singing in places that once banned Marian Anderson (like Constitution Hall in Washington), but mixing racial politics and her music wasn't to her taste at all, Rooks said.

That much was apparent in her singing. If African American singers from Anderson to Leontyne Price gave voice to centuries of oppression, Maynor represented respite and transcendence with the well-focused sweetness and tremulous vibrato of her lyric soprano, honed over years of private study in New York, and later, schooling at Princeton's Westminster College.

The honeyed radiance of her sound left even the most critical listeners agog. "She is the greatest thing I ever heard," proclaimed longtime Philadelphia Orchestra music director Eugene Ormandy. Another early champion was Boston Symphony Orchestra music director Serge Koussevitzky, who helped launch her career in 1939.

What those two conductors heard is captured in the Philadelphia Orchestra's 1999 12-disc Centennial Collection: More than any of the set's featured singers, Maynor effortless communicates across the decades in what was, for many of the postwar generation, a first exposure to a singular voice.

What's apparent from the 1940 recital, just published on the Bridge label after years of limited availability on the Library of Congress' own label, is how well she knew how to use what she had.

It's true that the voice has certain limitations - there was no Wagner in her future - as shown by one of the more stentorian Richard Strauss songs. But her emotional projection of the French language nearly eclipses her aristocratic use of English; unlike many American singers, her French doesn't sound drilled or schooled, but comes out with a natural suaveness. She traces the serpentine vocal lines in Bizet's "Adieux de l'hotesse arabe" with a new coloristic marvel unfolding in every phrase.

Whatever the language, she used consonants to dictate vocal color. That may sound like common sense, but it's not common practice. In effect, she put the message first, her voice second.

All these qualities come together in what was her signature piece, the aria "Depuis le jour" from Charpentier's Louise: It's one of opera's most rapturous moments to begin with, and shows her building a phrase in some typical broad operatic way and then capping it with a note of disarming softness and sweetness - arriving with little audible effort, like a gift from another dimension. Add to that her fast vibrato: It quivered with vulnerability.

Her most obvious legacy was, for years, the Harlem School, which she founded with $3 million she raised, tearing down the garages next to her husband's Harlem church and building a facility for dance, music and theater. When the school graduated to a larger building in the late 1970s, she stepped down. It is said she planned a concert return to the Library of Congress in the 1970s but then, for her own reasons, canceled.

There's a significant might-have-been element to Maynor's career: She claimed to have learned more than 20 operatic roles, though she never had a chance to sing them onstage. She's unimaginable in anything but good-girl roles like Micaela in Carmen - but what a good girl she'd have been.