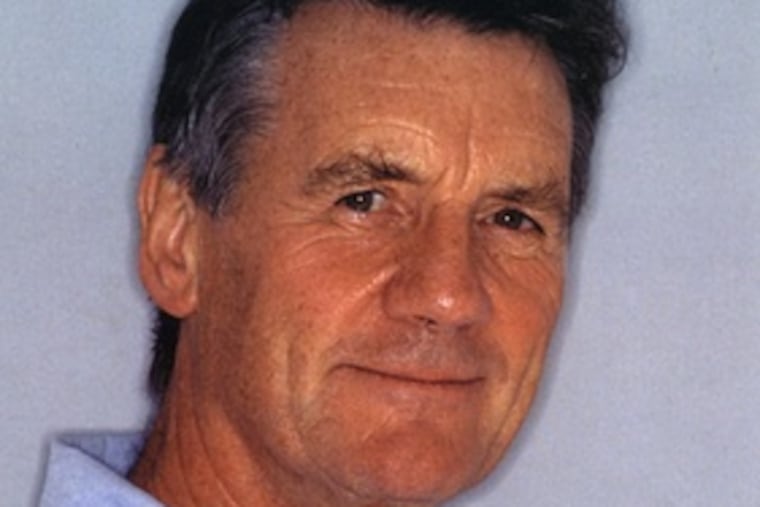

The lumberjack kept a log: Palin's Python diary

In 1969 Michael Palin quit smoking through sheer willpower. Having achieved a victory for mind over matter, Palin decided he would keep a diary for the next 10 years come hell or high water. Fortuitously the decade he chose to document would see the rise and fall and return of Monty Python's Flying Circus.

In 1969 Michael Palin quit smoking, a pastime he was quite fond of, through sheer willpower. Having achieved a victory for mind over matter, Palin decided to raise the stakes - he would keep a diary for the next 10 years come hell or high water. Fortuitously the decade he chose to document would see the rise and fall and return of

Monty Python's Flying Circus

. In clean, dispassionate prose spanning 650 pages, Palin documents the trials and tribulations of the daring, off-the-wall comedy ensemble from humble-but-edgy beginnings (the name

Flying Circus

was foisted on the lads by the bullying BBC) to globally recognized comedy institution (when translated for Japanese television, the show was called

Gay Boy's Dragon Show

). A promotional tour for

Diaries 1969-1979: The Python Years

brings Palin to Philadelphia tomorrow.

Question: What did each of your fellow Pythons bring to the table that made the show what it was?

Answer: I'll have a try. Terry Gilliam brought American-ness, which was very important. The rest of us were all from very similar background, all from provincial English towns and cities, so he brought this transatlantic perspective. Terry also brought the animation, which before then had never been used like that on television shows, and I think in many ways that was the key factor why Monty Python was remembered. Also it enabled us, as writers, to go from one sketch which didn't connect to another.

Terry Jones had a great persistence and commitment to Python, and like Terry Gilliam, he wanted to be a film director since the late '60s and that pushed Python beyond being a TV sketch show. Along with Terry Gilliam and myself, he also worked out the stream-of-consciousness theory of Python that gave the shows their unique flow.

Graham Chapman was possibly the best actor of us all and had a very manic kind of inventiveness. His mind would go in directions that nobody else I knew could or would, all these wonderfully weird connections that brought that surreal quality.

As with John [Cleese], he had this great ability to look just like the establishment, yet send it up completely from within. John had a certain manic intensity in his performances. Just wonderful to behold, and a very sharp writer.

There's a lot about John that you would think would disqualify him from doing comedy: this sort of intellectual legalistic mind and a rather serious way of looking at the world, and he could turn that a few notches one way or the other and it would produce the most wonderful comedy writing. Also, and this can't be underestimated, in comedy size is quite important.

Eric [Idle]? Very quick, very deft, very fast with jokes. Loved puns, loved wordplay, and could play those cheeky cockney characters, "Nudge, nudge" being the best of those. Outside of comedy he was also the best businessman amongst us, understood rights and deals, which the rest of us didn't.

Q: Yet in Diaries, you come across as The Sensible One.

A: Well, maybe because it's my diary and history is written by the winners. I avoid confrontation as much as possible, I prefer to get on with people. And I have a longer fuse than, certainly, John, who used to get very irritated at things. I brought a certain conciliatory side to Python. There were times when this one didn't want to work with that one and I just thought, "Well, I like them all so much," and I would often act as mediator on these occasions.

Q: The book spans 1969 to 1979, which is pretty much Woodstock to Studio 54, and yet there is almost no mention of drug use. How is this possible? It's the '70s!

A: We didn't really get involved in all that. We all did some marijuana. But it wasn't central to the work, and I think it's important to say that because there are people who say, "You guys must have been high as kites when you did this," when in fact we weren't, and with the exception of Graham, fairly sober.

Q: It's shocking to see how narrow the profit margins were for the Pythons in pretty much all the deals they struck. In fact, you write that half the Pythons were bankrupt by the end of the '70s.

A: Well, we never made a great deal from the BBC shows themselves - we were paid something like 200 pounds a week. We had a very strong and devoted fan base, but there weren't the big numbers that delivered a lot of money.

It wasn't until after Life of Brian [1979] that Python offered any real financial security. And as the diaries show, everyone was off doing other things - commercials, script-doctoring, voice-overs - just to support ourselves. There's never been crazy money in Python; it's now coming along pretty nicely, but to be honest Spamalot probably pays us more than anything else we've done. And that's Eric's show.

Q: Is it accurate to say that the Pythons were the comedy analogue to the Beatles?

A: People say that; I wouldn't have said that myself, but oddly enough Python was much liked by rock groups, and it wasn't just the Beatles. Led Zeppelin was one of the investors in Holy Grail. There was something about us that musicians particularly liked; maybe it was because we seemed a little dangerous, we weren't particularly establishment. They thought we were friends, and of course we were.

And it wasn't just George [Harrison]; Paul McCartney would stop recording his album just to watch Python when it first came on the telly back in 1969. The Beatles broke up almost exactly the same month that the Pythons were formed, I think it was October 1969.

Q: Any chance you guys will work together again?

A: No plans at the moment and I can't really see it happening, but there are different views on this. We have always said that Python was six people writing and performing resulting in a balance which for some extraordinary reason really clicked to produce an enormously diverse range of funny material. So without Graham, it's difficult.

We could get together and write, but then to perform, who plays Graham's parts? And if you bring somebody else in immediately Python isn't quite what it was, and I'm wary of that. Everyone is doing other things, and so I don't see a Python reunion on the horizon, but you never know.

Author Appearance

Michael Palin speaks at the Central Library of the Free Library of Philadelphia, 1901 Vine St., tomorrow at 7 p.m. Free. Info: 215-567-4341 or www.library.phila.gov.

EndText