Retraining brain waves

Neurofeedback is a burgeoning form of therapy that teaches patients exercises to strengthen weak patterns of brain activity - even kids with ADHD.

The boy cried almost every morning before going to kindergarten in Lower Merion, and he usually came home angry. His symptoms - inattention, impulsivity, extreme overreactivity, among others - led to a diagnosis of ADHD; the school suggested medication might be needed if his behavior didn't change.

Dismissing that solution, his parents searched for alternatives and discovered neurofeedback, a little-known form of therapy that essentially trains you to maintain better control through exercises tailored to strengthen weak (abnormal) patterns of brain activity.

"Last night, [he] actually wanted to read for the first time," Leah Frankel said after her only son's seventh session with Gary Ames, a psychologist in Bala Cynwyd. "I have a different kid." By the 11th session, the 6-year-old had stopped putting himself down when he knew he had behaved improperly. "He feels good about himself," his mother, a social worker, said after his 13th session two weeks ago.

From the beginning, Ames had recommended a course of 20 sessions that he expected would result in permanent behavioral changes. Frankel's health insurance does not cover the treatment, but she happily pays $75 every week (the minimum on Ames' sliding scale) for what she - not the therapist - calls "a miracle."

The concept of neurofeedback, also known as EEG biofeedback, dates back decades, to the discovery of measurable electrical impulses in the brain. Research and recent improvements in technology have made its use more practical for a broad range of clinicians.

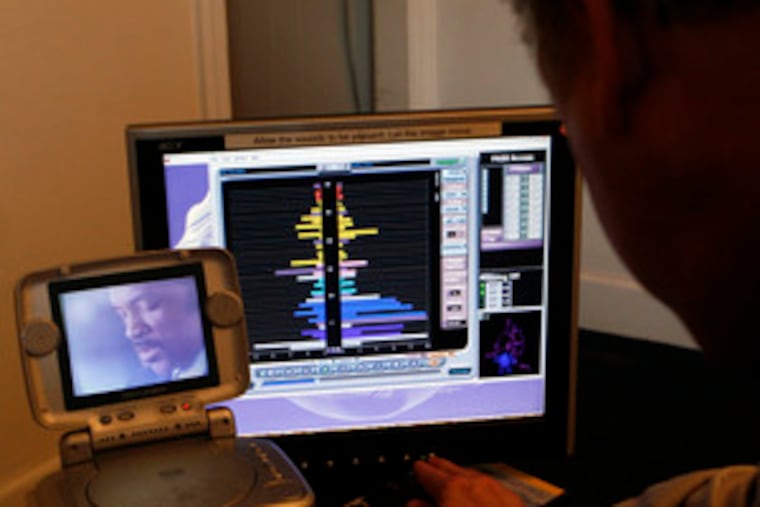

A typical session, 20 to 45 minutes long, involves watching a computer screen with electrodes pasted to your head. The brain scan - signals go out, not in - delivers feedback of neuronal activity. Patterns are visible to both therapist and client in real time.

Acting somewhat like a coach, the practitioner monitors brain activity and presents various computer exercises or games - a child might work to control the successes of hungry Pac-Man-type blobs, for example - to train the client to shift the particular brain-wave patterns that play a role in a given neurological condition.

The technique has been most widely studied and applied with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, although it is used to treat a wide range of disorders linked to abnormal patterns of brain waves.

The Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback says it is most effective for ADHD, anxiety, headaches, hypertension, urinary incontinence, and temporomandibular (jaw) disorders, although it is used to treat conditions ranging from autism to post-traumatic stress disorder.

But few health insurance companies cover neurofeedback, and many physicians and researchers question its effectiveness, although few contend it is unsafe.

David Baron, chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Temple University School of Medicine, says neurofeedback studies that he is aware of involved small numbers of participants and were not "double-blind," the gold standard in medical research that minimizes unrelated influences.

"Testimonials don't mean they're right," Baron says, adding that patients' claims aren't necessarily wrong either; he wants to see more definitive research.

Also at Temple, pediatric psychologist Brian Daly has reviewed numerous studies reporting positive results from neurofeedback. But the assistant professor in the College of Health Professions questions whether the findings are "due to the treatment itself or other non-specific factors like attention-from-therapist."

Like many other nontraditional approaches, the popularity of neurofeedback has nevertheless "exploded" in recent years, says Cynthia Kerson, executive director of the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research. The number of practitioners in the United States is now about 4,000, she says.

"The biggest problem in our field," says Kerson, whose organization is based in Richmond, Va., "is the lack of research money. The money is tied up with the pharmaceutical industry, and they are not interested in seeing us grow."

Most neurofeedback "trainers" are certified by the companies that sell brain-scan software and neurofeedback programs. Additional standards are set by the Biofeedback Certification Institute of America, but the practice is not generally regulated by the government. Therapists who use it - psychologists, social workers, nurses and others, many of whom integrate neurofeedback with other approaches, depending on a patient's diagnosis - often belong to professions that are licensed by the states, however.

The lack of insurance coverage means patients must be particularly committed - and have the financial resources to spend up to $135 a week for 20 to 40 weekly sessions.

An optional new diagnostic tool called Quantitative Electroencephalography, or QEEG, can add anywhere from $500 to $1,500 to the initial cost. The digital scan allows an individual's brain activity to be compared with patterns of normal brain waves stored in databases. The results can help fine-tune a treatment plan.

Reports from around the world indicate that neurofeedback is being tried for far more than serious neurological disorders. Neuroscientists at the Imperial College London reported that a controlled study showed brain-wave training improved performances by students at the Royal College of Music. Some members of New York's Metropolitan Opera have made similar claims. And Italy's soccer team was widely reported to have attributed its 2006 World Cup, in part, to neurofeedback training by four of its players.

Southwest of Harrisburg, a psychologist in Chambersburg treats local police officers who have been taken off the street due to anxiety. With active duty prohibited for officers on strong medication, several have opted for neurofeedback instead.

In Elkins Park, Laura Bell credits neurofeedback with relieving flares of anxiety associated with familial dysautonomia, an inherited disorder that causes nervous-system dysfunction ranging from a lack of tears to abnormal reactions to pain. Coping with the symptoms was difficult enough; excessive anxiety made her desperate for help.

A few months of neurofeedback from Celeste DeBease made a significant difference, said Bell, who continued seeing the psychologist in Bala Cynwyd. "I don't have any crises anymore," Bell, 33, said in an interview. "When I know attacks are coming, I know what to do."

After 20 years in clinical practice, psychologist Marvin Berman said he realized about a decade ago that "some of my patients were not neurotic, but they were brain-damaged." A search for other methods led him to biofeedback - the long-standing umbrella field of therapy that teaches awareness and control of bodily functions without the brain scan - and then to neurofeedback.

Berman has led local research studies on the effectiveness of neurofeedback for ADHD in a public-health setting, as well as for autism and Alzheimer's disease. He says he uses neurofeedback with about 40 percent of the patients he sees at his Lafayette Hill office, including some that he trains to practice with equipment they take home.

With Web cams and video-conferencing that can essentially put the patient in the room with the therapist, he predicts, "it's going to be the future."

The quest that led Michelle and Jaime Martinez to neurofeedback began after the Doylestown couple were given a dismal diagnosis for their 3-year-old son, whose severe auditory- and visual-processing disorders left his verbal skills two years behind the norm.

Multiple therapists and a variety of approaches yielded few advances. The couple came across neurofeedback on the Internet.

Their son Sergio, by then 6, could neither recognize numbers nor remember letters when he first saw psychologist Marged Lindner at her Philadelphia office. After three neurofeedback sessions, he was able to stay focused, gained the ability to memorize, and suddenly zoomed from a very limited vocabulary to, basically, talking.

Recalled his mother several months later: "We likened this to a window opening . . . where he would learn rapidly. And that's when we learned how smart he was."

Video demonstrations of neurofeedback's use in treating several disorders - plus guidelines on how to find a qualified practitioner: http://go.philly.com/healthEndText