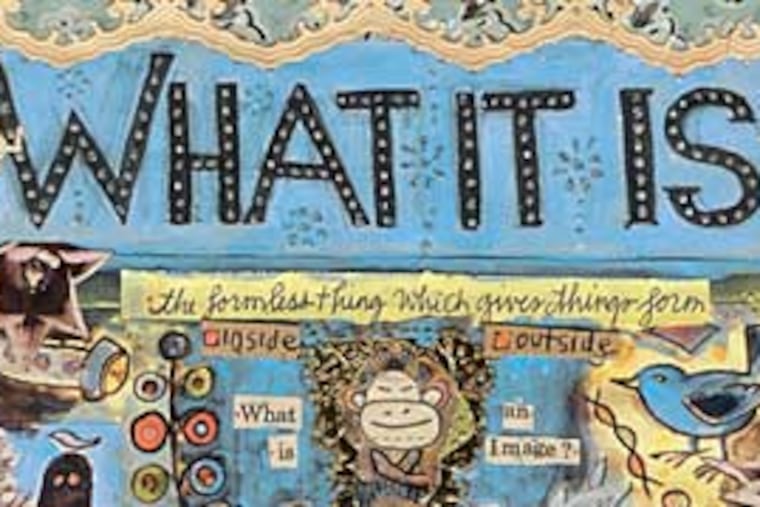

What is it?

Artist/writer Lynda Barry can't - or won't - categorize "What It Is," her highly creative memoir. "Crazy book" might work, she says.

Lynda Barry, prairie dog of the arts, has tunneled her way from underground comix (

Ernie Pook's Comeek

) to novels (

The Good Times Are Killing Me

) to the illuminated memoir

What It Is

, a transporting volume that pretty much defies description. Would she call it a memory map of creativity's source and flow?

"No idea how to classify it," the literary artist responds during a free-spirited volley of e-mails last week.

Nor does Barry have any idea of where to shelve it. "If there is a 'crazy book' section, it might go there," suggests the cartoonist, novelist and playwright whose Good Times enjoyed a successful Off-Broadway run.

Pushing herself for a working definition of What It Is, Barry, who will speak at the Central Library of the Free Library of Philadelphia tomorrow night, calls it "a textbook."

Accurate as far as it goes, but an understatement on the order of describing a Frida Kahlo painting as oil on canvas.

An outgrowth of "Writing the Unthinkable," a creativity workshop Barry teaches at venues across the country, What It Is is, among other things, an apparently free-form, but artfully sequenced, illustrated journal that proffers the key to unlocking recollections. Not just any recollections, but those stored in sense memory, smells, sounds, sights that make the creative juices flow.

One exercise Barry suggests is saying your first telephone number out loud. Do it. Barry says that when she recites, "Park Way Two Four Four Three Five, it feels like someone is saying my name."

Her book, a magic grab bag in which Barry has collected the disparate phenomena - images, doodles, snapshots, anecdotes - helps her get into the zone, and is intended to take readers there.

It does. An immersion in What It Is makes sleeping neurons wake up after a long Rip Van Winkle slumber, and primed to play.

"I really wanted to make a book that would make people itch to make a book of their own," she writes, "... itchy to get started on what most of us have wanted to do since we stopped using images on a daily basis in our lives. What kids call playing and what adults call creativity seem to be pretty much the same thing."

Some say that e-mail lacks tone. Not Barry's, whose electronic voice is as playful and plaintive as Ernie Pook, the comic that, when the New Wave in music and art broke on American shores in the '80s, shared the pages of underground weeklies with Matt Groening's Life in Hell.

Groening and Barry met as undergraduates at Evergreen State in Washington in 1974 and can be thought of as the Picasso and Matisse of alt-art, only friendly.

Groening, who first published Ernie Pook at the Evergreen State newspaper, tells the story about when he and Barry met. She was the girl in Dorm D legendary for having written to novelist Joseph Heller (Catch-22) and received a letter in return. In the return address, the resourceful Barry had scribbled "Ingrid Bergman."

Over the years, Barry, 52, has valiantly defended her belief that word and image are inseparable. (As she puts it in What It Is: "Pictures can help us find words to help us find pictures.")

"When I wrote Cruddy [her 1999 novel about an abused, resilient and resourceful 16-year-old] and wanted to include illustrations, I met with tremendous resistance from the publisher. . . . I was told that people would take the book less seriously if there were pictures in it."

"I think the resistance to comics as literature has to do with the possible unremembered sense of advancement from books with pictures to books with no pictures," Barry says. "To unite [word and image] again makes some people very uncomfortable."

What It Is is definitive proof that a work of art can also be a work of literature - and vice-versa.

"We didn't have any books in the house I grew up in," Barry recalls of her hands-off rearing in Seattle. Thanks to a supermarket giveaway, four books made it into the house. Tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. Heidi. The Arabian Nights.

"It was hard to find a place to read. That's why I loved the library," she recalls. To this day, the once "scraggly kid who didn't have a cared-for look" keeps a bookcase "with glass doors full of the oldest books I can find just so I can have that library smell when I need it. That's a smell that makes me feel that anything is possible."

Barry went to high school with Kenny G ("no comment"), college with Groening ("Funk Lord of USA"), and dated This American Life host Ira Glass ("I'll pass").

Once the ringmistress of the boho media circus, with regular appearances on the Letterman show, Barry has put down roots in Footville, Wis. Since 2002, she's lived in a converted dairy farm with her husband, Kevin Kawula, an artist/naturalist she calls a "plant guy," who runs a native-plant nursery.

As she describes it, the aromas of wood smoke, freshly baked bread, sun-dried laundry, and vegetables fresh from the garden permeate their home.

Life in Footville "was everything we ever wanted" until developers proposed an industrial windmill farm that would surround the Barry/Kuwala spread. These days, in addition to her other roles, Barry is endeavoring to restrict the development of wind turbines.

"They make an enormous amount of noise at times, especially at night, and have made homes unlivable," she notes.

"There may be a place for them," says the queen of green, "but beside people's homes and in bird migration flyways is not the place."

It's little wonder that the author/artist dedicated to sustainable living was moved to write/draw a book about how she sustains and renews her art. For art is, in the end, what keeps her going.

"I believe this kind of play/creative activity evolved along with all the other parts of us, like our thumbs and fingers," she writes, "and without it we go crazy."

.