Curtain closes for puppets

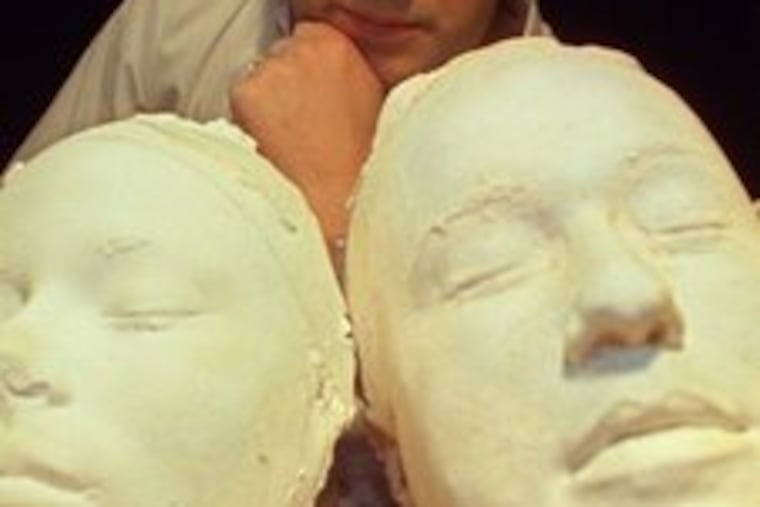

In the end, it took less than a month for Mum Puppettheatre to fold after the sudden departure last month of founder and artistic director Robert Smythe. A going-out-of-business sale to be held at the theater at 115 Arch St. all day Sunday will offer everything from puppets, masks and costumes to lumber and shelving.

In the end, it took less than a month for Mum Puppettheatre to fold after the sudden departure last month of founder and artistic director Robert Smythe. A going-out-of-business sale to be held at the theater at 115 Arch St. all day Sunday will offer everything from puppets, masks and costumes to lumber and shelving.

So how did things go so wrong so quickly for what Smythe proudly says was "the only brick-and-mortar regional theater in the U.S. ever to offer a full adult season of puppetry"?

Mum didn't fold for lack of effort. In 2006, the Philadelphia Theatre Initiative awarded the company $80,000 to develop this season's well-reviewed production of Animal Farm. The William Penn Foundation gave it $247,500, over three years, to "strengthen core programs/administration" and build staffing capacity.

The company was working with Chestnut Hill's Praxis Consulting Group on a three-year strategic plan, and, as former managing director Lisa Shelby recalled this week with frustration, "we had almost finished. . . . Mum was moving in a direction we wanted it to go in, to strengthen the infrastructure and continue to make the art it made. So it was really disappointing the stars aligned the way they did."

The stars augured very bad news this year, when the company learned it would not receive donations from several key institutional and individual sources. There were layoffs, and the struggle to continue producing became an issue of diminishing returns for Smythe.

"Our building was sold without our knowledge five or six years ago," he said Tuesday, "and with the boom in Old City property values, our rent went up 250 percent."

Along with rising rent was the challenge of what he termed a "changing philanthropic gestalt."

"Philanthropists in shining armor" have all but disappeared, he said, and "there's not as much of a culture here as in some other cities, where if people want certain experiences, they have a responsibility to help them continue."

In addition, he said, foundations, such as the Philadelphia Cultural Fund, "no longer give grants based on artistic merit, but on good management practices - they're giving management funds, not project funds."

There were problems in-house as well: Smythe said it had become clear that "the model for Mum's future success involved less participation by the artistic director." He asked himself, "Do I want to continue to be an administrator and make a home for artists who aren't me?"

The answer was no, and once he departed, Mum's board canceled the season's final production, The Adventures of a Boy and His Dog in Ye Olde Philadelphia.

Shelby, who was next to resign, explained her departure as the result of "stress, pressure, and a lack of resources. . . . I was the point person for this organization, and my ability to run it was very much hampered by these events."

Board president Candyce Wilson said there were "several entities" interested in carrying on Mum's work but that no agreement could be reached. So the board decided its only option was to shutter the theater, ending 23 years of groundbreaking influence on Philadelphia's theatrical landscape.

Since the Theater Alliance of Greater Philadelphia began handing out Barrymore Awards in 1995, Mum has captured 13, for everything from choreography to community service. The company has nurtured such artists as Barrymore winner and Drama Desk nominee Tobias Segal; Theater Horizon artistic director Erin Reilly, who produced Mum's The Velveteen Rabbit in King of Prussia; and puppeteer Aaron Cromie.

Cromie, who had been slated to direct Bill Irwin and Mark O'Donnell's adaptation of Moliere's Scapin next season at Mum, said he "was as surprised as everyone else" to learn of the company's demise; he doubts the production will happen elsewhere.

Cromie just ended a triumphant stint in Philadelphia Theatre Company's production of Irwin's The Happiness Lecture - further evidence of Mum's impact on local theater. Philadelphia Theatre Initiative director Fran Kumin said of Smythe, "When he started Mum, puppetry was very much on the periphery of theater, and that's all changed."

Smythe, too, recognizes the sea change in puppetry. "I remember back when we began, fighting tooth and nail to try to get an interview on [WHYY-FM's] Radio Times, and not getting it. Yet the week I left Mum, when WHYY re-broadcast its best of the week, one of those interviews was with Aaron Cromie. . . . I think we made it possible for a lot of people to stop saying, 'What?' and start saying, 'Of course.' "

Shelby, who includes Planned Parenthood as a previous employer, is circumspect about her future in the arts. "I've worked at places where the issues really are life and death," she says, "but nothing was as intense as working in this theater." Board president Wilson also feels the battle fatigue, admitting, "This was the only arts board I've ever sat on, and I think at this point I'll be a patron and lover of the arts."

But for Smythe, who just celebrated his 48th birthday, things are looking up. He's heading into a two-year playwriting fellowship at Temple and has a teaching stint next month at the O'Neill Puppetry Conference in Connecticut, and another in August at the Ko Festival of Performance in Massachusetts.

Of his future, he said, "If I could accomplish everything I did while balancing the books, imagine what will happen when I don't have to. Mum closed, but I'm still here."