Out from underground

Counterculture cartoonist R. Crumb's obsessions will be on display in a Philadelphia gallery show that covers his controversial career.

Robert Crumb recoils from himself.

"I can barely speak of my own dark side!" the hysterically misanthropic sex maniac and self-loathing father of underground comics exclaims in a speech balloon, as he covers his eyes in shame. "My addictions are so contemptible and pathetic I can't reveal them to the public!"

"You already have, dahling!" his cartoonist spouse, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, replies in a 2004 strip called Aline & Bob on Human Depravity. "It's all in your comics. . . ."

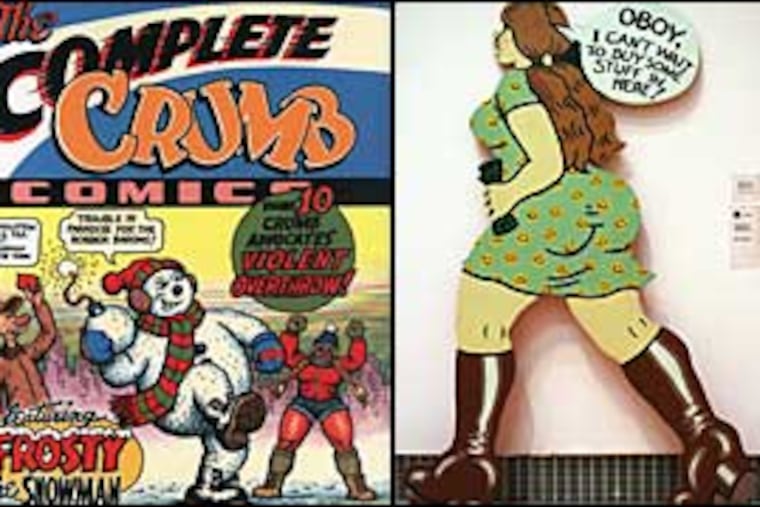

Indeed it is. And with the opening on Friday of "R. Crumb's Underground" at the Institute of Contemporary Art, the Philadelphia-born artist's obsessions - collecting old-time blues and country 78s, riding piggy-back on powerfully built women, and forever depicting, as he has put it, "the seamy side of America's subconscious" - will be on full display in the ICA gallery at the University of Pennsylvania through Dec. 7.

The exhibition, which originated at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco in 2007, is the largest ever mounted in the United States on the 65-year-old Crumb, who created the 1960s counterculture icons Mr. Natural and Fritz the Cat and was the subject of Terry Zwigoff's disturbing 1994 documentary film, Crumb.

The show spans the career of the bespectacled artist, whose psychedelic satires were first published in the Philadelphia underground newspaper Yarrowstalks in 1967. Its 100-plus original comic drawings, placemat illustrations, and three-dimensional figures include the life-size ceramic 1995 Devil Girl, whose contorted torso will greet visitors to the ICA's second floor galleries.

Together, they take the measure of the artist who lives with his wife in a picturesque village in the south of France in a house he purchased for six notebooks full of drawings.

Crumb has been called "the Brueghel of the last half of the 20th century" by art critic Robert Hughes - a high-art elevation to which Crumb responded with typical suspicion by declaring in a cartoon, "Broigel I ain't." And he's been compared to such social critics as 19th-century French artist Honoré Daumier as often as he's been labeled a pathological pornographer.

"Crumb is everything you would look for in a great artist," says Todd Hignite, the editor of Comic Art magazine and curator of the exhibition. Hignite interviewed Crumb at his home in Sauve, France, for the audio tour that accompanies the exhibit. The press-shy Crumb declined to speak for this story.

"He speaks very directly to a specific cultural moment unflinchingly, and he also explores universal themes and existential issues that keep you up at night," Hignite says.

Crumb's work has always sparked debate. Creations like Angelfood McSpade and Joe Blow have been criticized as racist and misogynist, and praised as critiques of racism and misogyny.

In the Crumb movie, Mother Jones editor Deirdre English says that Crumb "crosses the line between satire and . . . pornography" and that his art is the product of an "arrested juvenile vision."

Art critic Hughes, meanwhile, argues that that vision "emerges out of a deep sense of the absurdity of human life. There aren't any heroes or heroines, there aren't any villains, and the victims are comic. . . . Americans find that very hard to take because it conflicts with their basic mixture of Utopianism on one hand and Puritanism on the other."

As a boy in Philadelphia and the many other places where the family followed Crumb's Marine father, Crumb drew comics with his younger brother Maxon and older brother Charles, who committed suicide in 1992.

In Crumb, Charles describes their father as "a sadistic bully" and "tyrant" who broke Robert's collarbone when he was 9.

Crumb escaped through his art. He got a job with the American Greetings card company in Cleveland, where he met fellow record collector Harvey Pekar. (Much of their work on Pekar's American Splendor is on view at the ICA, as are Crumb's loving depictions of musicians, issued as "Heroes of the Blues," "Early Jazz Greats," and "Pioneers of Country Music" collector cards.

Shortly after moving to San Francisco in 1967, Crumb published Zap Comix, along with collaborators such as Victor Moscoso and Spain Rodriguez. Acid-trip-inspired characters like the devious Mr. Natural and his "Keep on Truckin' " drawings turned the scrawny pencil-wielder into a counterculture superstar.

"I was in ninth grade," remembers Charles Burns, the Philadelphia cartoonist and author of the teen horror magnum opus Black Hole. "A friend came up to me and said, 'Burns, there's this comic that you need to see. You're going to love it.' "

It was Zap Comix, Number 2. "It was a revelation to me," Burns says.

Crumb's draftsmanship was excellent - "It's a free line from his brain to his hand" is how ICA associate curator Jenelle Porter puts it. But the subject matter was mind-blowing. By unleashing his fears and fantasies - "He depicts his id in its pure form," his wife says in Crumb - the artist sent the message that everything was permissible.

"If Jack Kirby was the king of superhero comics, Crumb is the king of underground comics," says Brooklyn comic artist Dean Haspiel, who drew Pekar's recent graphic novel The Quitter.

Crumb's role in alt-comics history is similar to Bob Dylan's in pop music. He used established artistic forms, but opened up the doors to a more inward-looking expression that spawned hordes of imitators and, much to his distaste, caused people to view him as a spokesman for his generation.

He refused offers to draw album covers for the Rolling Stones and to host Saturday Night Live in the 1970s, and remained an outsider, always crankily harking back to a time he suspects was less sordid than our own.

"When you look at his art, it looks familiar," says Porter. "But when you start reading it - and a lot of it is rough stuff - you see the truth in it, and the humor, and the satire and irony. He came out of the period in the '60s that was ruled by hippies, but at the same time wasn't a hippie. He's looking at it with a screwball eye, saying, 'This isn't all it's cracked up to be.' "

"He has a huge, huge body of work," says Burns. "The thing I admire most about him is that he's never been satisfied with his early success. He's constantly challenging, and pushing, himself."

A good introduction to Crumb is 2005's R. Crumb Handbook, but no one volume can sum up a creative force who has illustrated novels by Philip K. Dick and a guide to Franz Kafka and is at work on drawing the Book of Genesis.

In Crumb's art, says "Underground" curator Hignite, "it's the whole tangled snarl of 20th-century American culture he's trying to come to terms with. And you can't just laugh at it or distance yourself from it, because he doesn't do that.

"It makes you uneasy, because it makes him uneasy."