Art: A campaign to set the record straight

Lewis Tanner Moore has spent decades collecting the art of African Americans.

Lewis Tanner Moore remembers that in 1969 he took a class in art history while a student at Chestnut Hill Academy. The course text was H.W. Janson's

History of Art,

which had been the definitive reference for several generations of young scholars.

Moore further recalls that he was struck by the absence of any African American artists in the book. When I was in college, I, too, had noticed that Janson's slighted American art in general, as well as art made by women. In those days, the art-history bible was resolutely white, male and European.

This discovery disturbed Moore not only because he's African American but because he's the great-nephew of an important black artist, Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts with Thomas Eakins.

Young Moore decided that the record needed to be corrected and began a lifelong effort to do so: With the help of an art teacher, Barbara Crawford, he borrowed works by black artists from friends and family and organized a small exhibition at the school.

The show wasn't a flash in the pan fueled by student idealism. Rather, it inspired Moore to begin a collection that, after almost four decades, has grown to hundreds of objects in a variety of media. Now a small portion of that collection has gone on view at Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill in a show called "In Search of Missing Masters."

The collection sprouted from family holdings, which Moore lived with as a child and young man. He has expanded it exponentially in several directions to include current and historical figures, famous and obscure ones and men and women.

The exhibition comprises 135 paintings, sculptures and works on paper by 94 artists; of these, about 70 percent come from the Philadelphia region. There are many national names as well, from Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence to Sam Gilliam and Barbara Chase-Riboud.

Moore's dedication to his goal of identifying black artists who have escaped art history's relentless dragnet deserves the highest praise. Some people collect art as an investment or to acquire social cachet, others because they become enchanted with a particular artist or movement. But Moore collects because he wants the public to become aware of creativity that was ignored or suppressed.

He achieved this, almost miraculously, with limited financial resources, on the salary of a Philadelphia civil servant, in the city's department of public health.

Woodmere mounted this exhibition as part of its continuing intent to showcase local collectors who specialize in Philadelphia-area artists. In this case, the collector's accomplishment is as much the point of the show as the achievements of the artists. Many are represented by a single work, some by two, and a few, including Moore's great-uncle, by three.

Such a kaleidoscopic mix doesn't allow a reasonable assessment of any one of them. It is possible, though, to become aware that talented black artists are far more numerous than one realized.

In this regard, the exhibition title is slightly hyperbolic. Many of the artists that Moore has collected might be "missing" from mainstream art history - or even from African American art history - but few could be legitimately characterized as "masters." In any generation, there are likely to be relatively few of those, even given that the term is ambiguous.

So we're not trying to discover masters at Woodmere, we're looking for artists who produced interesting, competent, distinctive work, whether rooted in black experience or closely tied to modernist aesthetic currents. Black American artists traditionally traveled both pathways and, as the Moore collection indicates, continue to do so.

What one takes away from this exhibition depends in large part on the degree of one's familiarity with black art. For most visitors, the show probably will break down into three tiers. None include self-taught or folk artists such as Horace Pippin; Moore favors artists with formal training.

At the top are those artists, living and dead, who by now have become established in the American canon - artists such as Tanner, Edward Mitchell Bannister, Hale Woodruff, Lois Mailou Jones, Faith Ringgold, Elizabeth Catlett, Bearden, Gilliam, and Lawrence. This group is larger than one would expect in a collection formed by someone lacking Bill Cosby's deep pockets.

The middle tier consists of artists who have developed substantial reputations locally or regionally, such as Paul Keene, Raymond Steth, Richard Watson, James Brantley, Allan Edmunds, Edward Loper, Columbus Knox, Charles Burwell, Donald Camp, Barbara Bullock, Barkley Hendricks and Humbert Howard, to cite a representative few at random.

Moore had been exceptionally thorough with this second tier. As you move through the show, you'll find yourself trying to think of people whose work is missing.

For visitors familiar with black art, or drawn to it for cultural reasons, the show's third tier should prove to be the most nourishing. These are artists you probably haven't encountered, in either exhibitions or books. These so-called missing masters are the artists you'd like to see in greater depth.

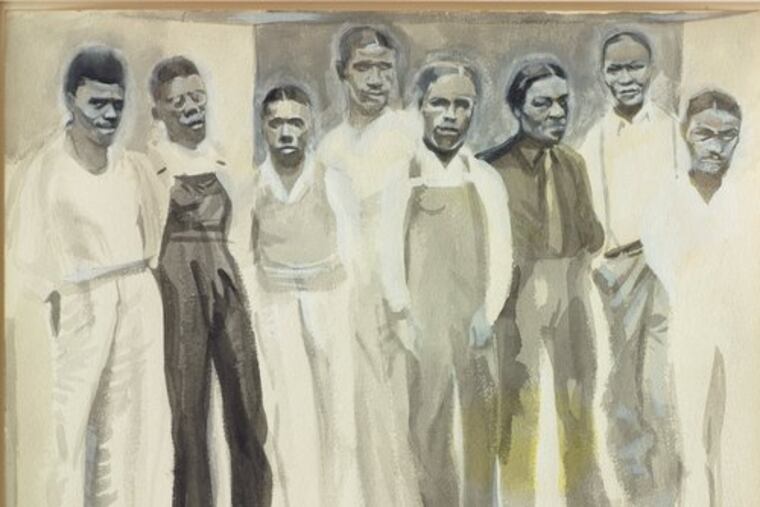

Rex Goreleigh (1902-87), born outside Philadelphia and trained in New York and Paris, offers a prime example. He taught in Harlem - Lawrence and Robert Blackburn, also in the collection, were pupils. He also worked in Chicago and in Princeton, where he established a teaching studio in 1947. Two works, a 1940 watercolor called

Church Supper

and a 1965 oil, are among the exhibition's most distinguished.

Reginald A. Gammon (1921-2005) and Charles A. Pridgen (1922-91), both Philadelphia natives, were unknown to me before I saw them at Woodmere; like Goreleigh, both merit a longer look. In his later years, Gammon made portraits of prominent black Americans like Tanner. Pridgen, like Gammon a graduate of Tyler School of Art, was more inclined toward modernism, as seen in a drawing of figures in an interior.

"In Search of Missing Masters" is not only a richly layered exploration of African American art, it also offers a serviceable primer for newcomers to the subject. Moore has filled in the blanks in Janson's survey with remarkable meticulousness and passion for a cultural tradition that has languished too long in the shadows.

Art: Correcting History

"In Search of Missing Masters: The Lewis Tanner Moore Collection of African American Art" continues at Woodmere Art Museum, 9201 Germantown Ave., Chestnut Hill, through Feb. 22. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays and 1 to 5 p.m. Sundays. Admission is free. Information: 215-247-0476 or

» READ MORE: www

. woodmereartmuseum. org.