A model of resilience

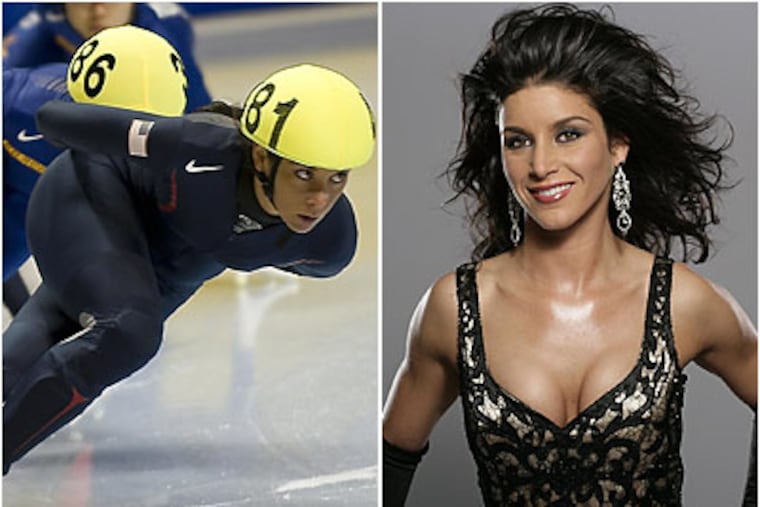

Down often but never out, champion speedskater Allison Baver is now eyeing a second career.

Allison Baver's speedskating career has been marked by seemingly devastating setbacks - always followed by remarkable successes.

After she took to the ice in the late 1990s, her competitive run could have been ended by an on-ice collision that left her with nearly 50 stitches in her face - yet she dared to return to skating and made the U.S. Olympic teams in 2002 and 2006.

Out for a year with a leg injury, she almost didn't make it to the 2007 National Championships - but somehow recovered in time to win the short-track title.

After another injury and heart problems put her in a wheelchair, it seemed she would never skate again - now she's training for the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver.

"Her success is a result of a lot of determination and a lot of hard work," said Shawn Walb, who coached Baver early in her career. "She establishes goals and has the stick-to-itiveness to keep chugging along."

Now Baver, a native of Reading, has another goal: making it as a model. She doesn't necessarily aspire to the runways of New York or Milan or the pages of Vogue, although that would be nice. Rather, she wants to inspire young girls, to show them that women can be strong and successful and don't have to fit the model mold to be beautiful.

"You can be yourself and you can be beautiful. You don't have to be super-skinny," Baver, said. "I want young girls to know you can do anything you put your mind to."

A few months ago, Baver, 28, signed a contract with Wilhelmina Models as the agency moves into the world of athletics, having recently signed seven members of the Ladies' Professional Golf Association to exclusive contracts, a representative said. She appears in the December issue of Women's Health magazine. ("Page 80," said her mother, Dixie Baver, who may have cleaned out newsstands in the Reading area.)

"She's more than a role model," said John Schaeffer, a strength and conditioning coach who helped Baver reclaim her form after a recent injury. "She's an inspiration."

In an event that can resemble roller derby, short-track skaters whiz around the ice, sometimes wiping out and taking their competitors with them. Baver said people call it "the NASCAR of the Olympics." At the top of her game, she whips around the rink at about 35 m.p.h.

It can be rough and dangerous, and Baver has the scars to prove it. Short-track skating's biggest star is probably Apolo Anton Ohno, the two-time Olympic gold medalist and Baver's former beau.

She started roller-skating on old-fashioned four-wheeled skates in elementary school, then moved on to inline skates. She didn't take to the ice until her teen years.

When she was starting out, she collided with another skater during a race in Maryland and ended up with a gash across her forehead and cheek that at some points cut to the bone. She needed 48 stitches and, in her own words, "looked like Frankenstein."

Such an injury may have scared some people out of the rink. Baver was soon back in training. Making the 2002 Olympic team, and walking into the opening ceremonies in Salt Lake City, "just gave me chills," she said.

"I realized I'd accomplished my dream," Baver said. "It was right after 9/11 and there was a whole stadium of people from different countries cheering, 'USA! USA!' I felt the spirit of the Olympics."

Early in the 2006 Olympics in Turin, Baver suffered an ankle injury and eventually found herself unable to race. It took more than a year for her to heal, time she used wisely: being with her ailing grandmother and visiting her brother, who was attending Temple University. After doing off-ice training, she stepped onto the ice for the 2007 National Championships - and won.

Then the most recent injury occurred: A hard fall left her flat on the ice - "I thought I was paralyzed," she said - and she injured the same ankle, only in a new way. She sprained her back and bruised some bones. Her heart rate became erratic, pounding as if she were racing when she was standing still.

But she struggled back. Working carefully with Schaeffer, she modified her workouts and diet, and now Schaeffer believes she may be in the best condition of her career.

"It probably would have made anybody else fold and quit," said Schaeffer, who trains Ohno and other athletes. "Her desire and will to be the best and win is probably second to no other woman in the world for what she does."

While skating up a storm, Baver has also earned a bachelor's degree in marketing and management from Pennsylvania State University and a master's in business administration from the New York Institute of Technology. (Donald Trump once considered her as a contestant for The Apprentice.) She'd go hard six days a week, Dixie Baver said, and on the seventh day lock herself away with books and computer.

Now she's gearing up for the 2010 Games and trying to get her nonprofit organization off the ground. Visiting her brother and meeting Philadelphia youth sparked the idea for Off the Ice - its mission is to instill character and encourage goal development in young people by getting them involved in sports.

In January, MBA students at Alvernia University in Reading will study Baver's idea and help make it a reality, she said.

As for the modeling, Baver said it's really not that much of a stretch. She's always been eager to take off her helmet and let her hair down. Her mother notes that, "When Allison wins, as soon as she's done skating, she has to be in the bathroom and do her hair."

Baver is excited for the new challenges modeling will bring, but no one should expect her to be typical.

"The first photo shoot I did, I was like starving, and there was nobody eating," she said. "It was like, 'OK, can I eat some pizza?' "