A man of morals

The word comes up frequently as writer, painter and activist Breyten Breytenbach talks about his homeland, South Africa, and America.

give me two lips

and bright ink for tongue

to write the earth

one vast love letter

swollen with the milk of mercy

- Breyten Breytenbach, "rebel song"

The predominant yardstick of your government is not human rights but national interests.

- Breytenbach, "Letter to America"

Breyten Breytenbach offers a gracious if slightly melancholy smile as he greets the 50 students, scholars and poetry aficionados crammed into the intimate space of the University of Pennsylvania's Kelly Writers House.

The 69-year-old South African poet, novelist, memoirist, painter and activist has a closely cropped gray beard and an impressive shock of gray-white hair. He's wiry and tall.

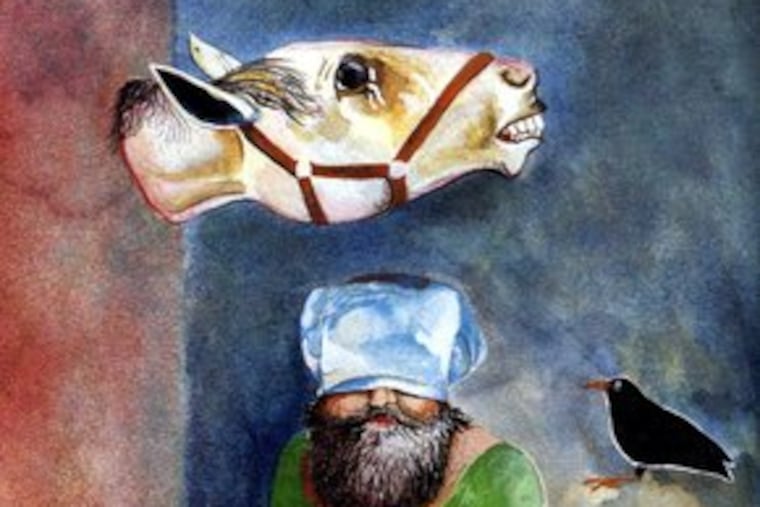

Breytenbach, whose most recent books include Windcatcher: New & Selected Poems 1964-2006 and All One Horse, a collection of ironic, surreal prose poems and fables illustrated with his own paintings, appears nervous.

It's odd to think of this sophisticated student of art, history, literature and philosophy, who writes passionate, imagistic poems, as nervous.

It's even odder to think of the former political prisoner as nervous. Beginning in 1975, Breytenbach toughed out two of his seven years in prison for antiapartheid activities in solitary confinement, in Pretoria Central Prison's maximum security wing. (Sentenced to nine years, he was freed early, thanks to a campaign led by former French President Francois Mitterand.)

The poet, whose cell was next to death row, tells the Penn audience that prisoners headed to the gallows would spend their final week in a communal cell. "They spent the entire week singing together," he says to the group gathered on Dec. 4, now reading from a poem. "The voices of the older men carried those of the younger ones - 'Don't be afraid.' "

Breytenbach was born in 1939 to an eminent, if humble, Afrikaaner family that traces its ancestry to South Africa's first white settlers, in the 17th century. Speaking by phone from his home in New York, where he holds a chair in creative writing at New York University, Breytenbach said his revolt against the apartheid system began as part of his teenage rebellion "against what I considered to be the hypocrisy of the religious and cultural leaders of my tribe." He said he was outraged at "the distance between what they claimed to believe" as Christians, "and what they actually did to others - to the so-called colored."

At the University of Cape Town, he joined protests against new laws aimed at "segregating the universities once and for all."

In the early poem "rebel song," he utters a plea for the strength to continue speaking out against injustice:

grant me a heart

that will pulsate its throb

more strongly than the white thrashing

heart of a terrified dove in the dark

knock louder than bitter bullets

In 1960, Breytenbach opted for self-imposed exile. After a two-year tour of Europe, he settled in France, later becoming a French citizen.

In 1962, he became a criminal under South African law and was banned from returning. His crime? Interracial marriage. Breytenbach had married a French woman of Vietnamese descent, Yolande Ngo Thi Hoang Lien, violating South Africa's Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (1949) and Immorality Act (1950), which criminalized interracial sex.

He returned under a fake passport in 1975, and was caught and imprisoned.

Breytenbach's artistic career began in 1964 with a hat trick, as he published his first book of poems, The Iron Cow Must Sweat, and first volume of prose, Catastrophes, and had a first exhibition of his paintings, at an Amsterdam gallery.

Arguably, his best-known works are four memoirs coinciding with visits to South Africa, including the celebrated 1986 True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist, which details the horrors of prison.

Breytenbach, whose influences range "from the Chinese masters to Borges to poets like Mayakofsky, Mandelstam to the Beat generation," has never been able to stick with one genre. He is famous for experimental works that mix autobiography, fiction, poetry and criticism.

But for all his postmodern playfulness, Breytenbach insists that, like that of other African writers, his work can't help but be suffused by political and ethical concerns.

"We in Africa instinctively touch upon the subjects that are very important to our people," he said. "[We are] political nearly by definition."

Breytenbach holds that the artist's duty is to help people refine and expand what he calls the moral imagination.

"The artist does this by . . . questioning and revising all the assumptions of certainty we have, including any certainty we have about the meaning of words," he said. "We must go beyond our own limitations and question the very purpose of our lives."

Most urgently, the artist needs to continue voicing our moral ideals, Breytenbach said, however difficult they seem. If "politics is the art of the possible," he said, "revolution is the necessity of the impossible."

In a number of controversial essays couched as open letters, Breytenbach also addresses specific political issues. In the scathing "Letter to America," Breytenbach charges President Bush's administration with committing innumerable human rights violations. And he laments the political apathy that he says has gripped Americans since the end of the Vietnam War.

In "An Open Letter to General Ariel Sharon," Breytenbach takes the Israeli government to task for its treatment of the Palestinians - though he also criticizes those who equate Israel's policies with apartheid.

"I'm really concerned by what is this lack of continuity of moral history," he said of his reasons for writing the Sharon letter.

He said Jews, "who have this collective memory of what has been done to them as a people," have developed powerful ethics that imbue Western culture. Yet, he asked, "how did they get to a position that they are allowing this to be done to another people as a people?"

Breytenbach, who spends part of the year at the Gorée Institute, a cultural center he founded in Senegal, has also caught flak from some liberal pundits for his latest open letter, a passionate, deeply respectful yet equally critical letter to South African leader Nelson Mandela. "Mandela's Smile: Notes on South Africa's Failed Revolution" appears in this month's issue of Harper's.

Breytenbach, who cofounded University of Natal's Center for Creative Arts in Durban, South Africa, in 1995, praises Mandela's "benevolence" for seeking reconciliation rather than reprisals when he took power after the fall of apartheid. But, he said, the country is gripped by a corrupt government, lawlessness, and a general loss of moral concern.

"This has been a failed revolution in terms of the spirit," he said, "in terms of the social commitment and the moral responsibility" of each person for another.

Breytenbach bristles when asked whether his vision of moral accountability wasn't merely an idealist's dream.

"I am very much aware of the gap between the ideal and . . . the pragmatic possibility," he said. "The pragmatic argument is a powerful one," whether it is an argument about America's need to secure cheap oil or Mandela's need to make political compromises.

But, Breytenbach insisted, "it is as much important to keep alive the ideal" - a job, he said, that belongs by rights to writers and artists. "It is in the awareness of this continuing gap that one can hope for change."

But hope is precisely what is missing from Breytenbach's assessment of Africa's future. "I'm pessimistic about the short term, yes even for the middle term," he admits, adding that change won't come as long as Africans wait "for others to do it."

"What is missing in Africa are people who would make a difference, including intellectuals. People who have the sense that we need to do this for ourselves," rather than wait for outsiders to help us. "We have to find it from within our own society to move toward a modernity that would enable us to live with dignity."

Even as he rejects help from without, Breytenbach denies appeals that we wait for help from above in the pointedly humanistic "prayer," a riff on the Lord's Prayer:

But let us deliver ourselves from evil

So that we may settle the score of centuries

Of stored exploitation, plunder,

and treachery,

And the last capitalist dies, poisoned by loot.

. . .

Ay man! Ay man! Ay man!