Voices of the past, in shimmering new translations

Ours is a great era of translation. It has been going for at least two decades now, bringing fiction, drama, and especially poetry into English for our times.

Ours is a great era of translation. It has been going for at least two decades now, bringing fiction, drama, and especially poetry into English for our times.

Paula Dietz edits the much-respected Hudson Review; its most recent issue is devoted to translation, with works by Sophocles, Victor Hugo, and others, including a new version of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. She agrees that "many more poets than before are interested in translation" and thinks "poets are drawn to the challenge . . . the discipline appeals to them."

Why the surge? Al Filreis, Kelly Professor of English and faculty director of Kelly Writers House at Penn, says it's the globalized age: "The digital era means all poetic forms and media from all places circulate rapidly and incessantly. Language differences, not distances, are the only barrier. Translation thus breaks down the final obstacle to the true international poetry community."

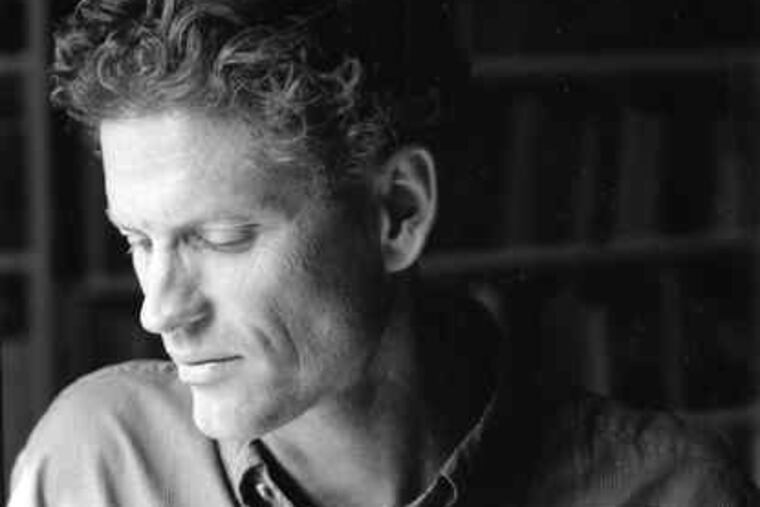

C.K. Williams, a Pulitzer-winning poet and teacher of translation at Princeton, sees it as "a cyclical process." In a talk on "Globalization and Poetry" for the Art Institute of Chicago last year, he spoke of a similar explosion of translation in the late 1950s and early 1960s: "I believe that our mostly unconscious realization during those years, that we were at a dead end, drove many of us to ransack literatures other than our own." Could the turn to translation signal a similar dissatisfaction among today's writers?

Translation is hot among publishers, too. Several translations have sold well in the last 20 years, including Seamus Heaney's Beowulf, Robert Fagles' Iliad and Odyssey, and, in the prose world, the works of Gabriel García Márquez and Roberto Bolaño. We're even seeing a Nordic mystery boom.

Burton Raffel, professor emeritus at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, is an extraordinarily accomplished translator whose 1963 Beowulf has sold more than a million copies. When he shopped around his first book of translations in the '50s, he says, "it was rejected by 43 publishers in five years."

Publishers sent it to scholars, who'd grouse that it wasn't scholarly. "But the academic hold on all this has been broken," says Raffel, whose new translation of the 11th-century Spanish epic The Song of the Cid will be out this month. "Academics no longer control publication or the critical outlets; there's much more openness to 'writer types' doing the translations."

Three recent fine translations stand for this trend. Want to read three towering dramas that tell one of the greatest of all stories? Read Anne Carson's An Oresteia. Ever wondered what good Roman poetry was like? Try J.D. McClatchy's collection Horace: The Odes. And if you want the panorama of 2,600 years of Chinese verse (and you should), dip anywhere into David Hinton's Classical Chinese Poetry.

Carson, a Canadian poet who teaches at the University of Michigan, is one of my favorites. Most people have heard of The Iliad and The Odyssey. Far fewer know the Oresteia, a story cycle that follows Agamemnon home after the Trojan War. Tragedy, blood, and caustic human blindness ensue, landing his son Orestes in an impossible dilemma. Carson translates one play each from Aeschylus (Agamemnon), Sophocles (Elektra), and Euripides (Orestes), for a brand-new cycle.

Her translations are in this moment's English, drolly modern even as they remain faithful to the plays. This is not the condensed, wry idiom of Carson's personal poetry. Instead, she loosens things up, goes for the conversational, with language to work well on stage. And it's getting a chance to do just that, starting today - An Oresteia begins a run at the Classic Stage Company in New York through April 19.

Caution: The one thing translation is not is a word-for-word rendering of the original. As Raffel says, "No one can produce in one language exactly what happens in another." Try, and you'll get nonsense and failure. As Raffel says, "You don't translate what a man says; you translate what he means," a paraphrase of Ezra Pound's words to his German translator. Carson's very good at translating what a great writer means. Here are the Watchman's famous first lines from Agamemnon, which nearly word for word, might be:

Oh gods, I beg you to deliver me from this task.

For a year I have been on guard

On the roof of the house of the sons of Atreus,

resting on my arms, in the manner of a dog.

Not poetry. Here's Carson:

Gods, free me from this grind!

It's one long year I'm waiting watching waiting -

propped on the roof of Atreus, chin in my paws like a dog

Energy, humor, the yawn of the watchman's boredom. We hear the wordplay of Aeschylus, the tough irony of Sophocles, and the perverse subversion of Euripides. Here's the Chorus of Orestes: "The weirdness goes on. It just goes on. / Here's Orestes. Got his sword out. Looks pretty excited."

Against this come explosions of violence, as when Elektra says of her brother Orestes, "His mother's blood comes quaking howling brassing bawling blacking / down his mad little veins."

Horace is one of the best-known poets in the world. Along with Virgil and Ovid, he was of a generation that slaved to make Latin a literary language.

J.D. McClatchy, a celebrated poet, editor, and scholar, has assembled an all-star team to create this sparkling collection of odes. The lineup - Robert Bly, Robert Creeley, Linda Gregerson, Donald Hall, W.S. Merwin, Paul Muldoon, Robert Pinsky, C.K. Williams, and others - is breathtaking. They're not only good poets; they're also good poets who hear Horace and bring him across. They hear laughter where there's laughter, sorrow where there's sorrow, and take all sorts of risks.

In one daredevil act, Heather McHugh gets the high honor of translating Ode I.11, with that resounding phrase carpe diem, "seize the day." Horace ends with

dum loquimur, fugerit invida

aetas; carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero

Literally, that's something like

As we speak, jealous time steals away;

seize the day, trust the future as little as possible.

Blah. McHugh has this:

Think less

of more tomorrows, more of this

one second, endlessly unique: it's

jealous, even as we speak, and it's

about to split again . . .

She doesn't - gasp! - even translate carpe diem. What a hair-raising gamble; I'm not even sure it works. If it does, we'll be so desperate at time stealing away we'll grab the moment without being asked.

David Hinton has been translating Chinese poetry for more than a decade. His new anthology gives us, for the first, best time, the sweep of this tradition in excellent English poetry. As Hinton writes, this may be the longest unbroken literary tradition that exists, starting around at least 1400 B.C. and still going. We know Chinese poetry through the efforts of Pound, who helped supercharge modern poetry. It should be said, though - someone has to say it - that Pound's renderings of Chinese verse were idiosyncratic and, in some respects, misleading.

Hinton's are neither. His triumph, across hundreds of poems, is to suggest the range of this work, its many different voices, from the seductive purr of the "Lady Midnight" poet -

A gauze skirt's grace is light and airy:

if it slips open, blame a spring breeze.

- to the experimental, harsh, almost modern-sounding lines of Meng Chao:

Frozen into knife-

blades, rapids have sliced ducks open,

hacked geese apart. Stopping overnight

here left their feathers scattered, their

blood gurgling down into mud and sand.

- to, finally, what is, hands down, the greatest tradition of nature poetry ever, as in Hsieh Ling-yün:

. . . slow waters silent in their frozen beauty

and bamboo glistening at heart with frost,

cascades scattering a confusion of spray

and broad forests crowding distant cliffs

How happy that the vivid, calm grandeur of these poems now abides with us, in English. And how great: We have a new Horace in which he speaks directly to us; a new Oresteia with rasp, sass, and pungency; and millennia of Chinese verse. All are as fresh as if they were written now. Which, thanks to a new generation of poet-linguists, they really are.