Galleries: Video-art pioneer explores physical nature of language

Even before you walk into the Slought Foundation to see its current exhibition, "The Art of Limina: Gary Hill," a window display stops you in your tracks. On a small, casually positioned monitor, a pair of seemingly disembodied arms gesture animatedly, accompanied by a synchronistic soundtrack of a man's voice. It's not funny-weird like a Tony Oursler video sculpture. It's sincere, and the product of a very different, unironic sensibility.

Even before you walk into the Slought Foundation to see its current exhibition, "The Art of Limina: Gary Hill," a window display stops you in your tracks. On a small, casually positioned monitor, a pair of seemingly disembodied arms gesture animatedly, accompanied by a synchronistic soundtrack of a man's voice. It's not funny-weird like a Tony Oursler video sculpture. It's sincere, and the product of a very different, unironic sensibility.

Since the '70s, video-art pioneer Gary Hill has been deploying image, text, and sound to explore the physical aspects of language, a preoccupation that becomes clear once you enter the darkened rooms of the Slought Foundation.

First up is the largest and most recent of Hill's pieces, which is debuting in this exhibition. Up Against Down (2008) is an installation of six large projections that shows various parts of Hill's body pushing against what appears to be black, possibly empty, space, accompanied by the sound of low-frequency sine waves. It's a Wagnerian effort that brings to mind a number of things simultaneously: conceptual art of the early '70s (Vito Acconci's notorious Seedbed, in particular), a movement that clearly influenced Hill, who began his career then; John Coplans' black-and-white photographs of his own naked body from the 1980s; and the experiences of contemporary prisoners of war.

Like many Slought exhibitions, though, this one focuses on earlier, lesser-known works, all of which offer fascinating glimpses into Hill's artistic development. Processual Video, from 1980, shows a thin, white line on a black screen that rotates, widens, and narrows as if anticipating the words of a text spoken by Hill in a monotonous voice. Figuring Grounds, shot and recorded in 1985 (and edited and completed in 2008), is as mesmerizing for the performances of George Quasha and Charles Stein, who carry on a remarkably deft, improvisational duet of spewing out related words and non-words, as it is for Hill's filming. (The two were able to monitor themselves on a closed-circuit system and somehow respond to Hill's changing images of them.)

Two long films, Incidence of Catastrophe (1987-88) and 1984's Why Do Things Get in a Muddle? (Come on Petunia) borrow some of the conventions of early feature films. They're eerie and dreamlike, with none of the staccato beat of his short, more obviously conceptual, pieces. You sense they'd be best-suited to a movie theater, which is probably why both are confined to a small room at the back of the gallery. And yet in both, Hill's audacious, bizarre experiments with words and sound within a semi-narrative framework are spellbinding.

Contemporary temporary

The 19th-century French word for a temporary encampment has inspired this year's guest-curated exhibition at Vox Populi.

"Bivouac," organized by curator and writer Fionn Meade, looks at work that is improvisational and rapidly constructed, and at seven artists (none of them Vox Populi members) who take variously dadaist, constructivist, and fluxus-like approaches to said work. If you were expecting a bricoleur along the lines of a Jessica Stockholder or a Tom Sachs, though, forget it. "Bivouac" is composed almost entirely of videos.

You sense that Alex Hubbard's videos are the lodestone of Meade's exhibition. Materials and objects are shown being assembled, dripped with paint, ripped apart, and almost literally tarred and feathered. His paintings, of which there are two, appear to have undergone similar ministrations.

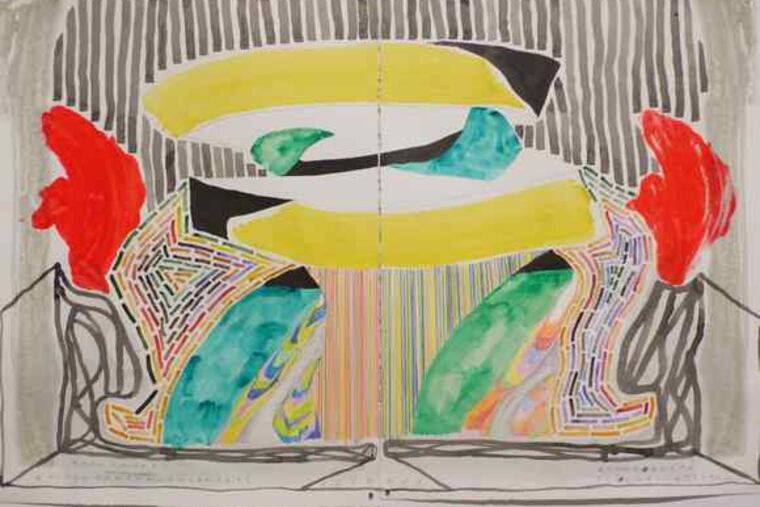

Steve Roden's direct animation layered over an educational film from the 1950s, which interprets a fluxus score by the concrete poet Jackson Mac Low, fulfills Meade's directives as well, as do his watercolor and colored-pencil drawings, which he makes according to rule-based procedures.

Kazimir Malevich's stage designs for the futurist play Victory Over the Sun (1913) and his painting Black Square (1915) are said to have inspired Anna Molska's video Tanagram, in which two helmeted, nearly nude young men are shown assembling huge wedge-shaped blocks into a larger geometric shape. But the work of Matthew Barney is more likely to come to mind.

At first, Meiro Kozumi's strange, affecting video Craftnight - of a man trying to copy a small clay sculpture in front of him, but letting his emotional recollections of his last encounter with his father guide his hands (the resulting sculpture looking like a mushy meltdown of clay) - seems an uncomfortable fit. In hindsight, however, it fits this show's theme perfectly.

"Bivouac" also includes videos by Lucy Raven and Sung Hwan Kim; photographs by Sara VanDerBeek; and two historical films - René Claire's Entr'acte" (1924) and Hans Richter's Ghosts Before Breakfast ("Vormittagsspuk") (1928).