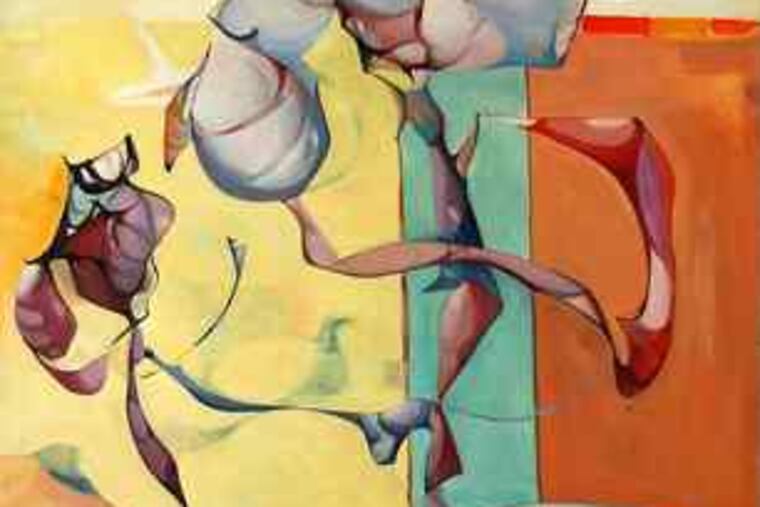

Art: Abstract, mystical surrealism

A dual-venue show explores Phila. painter Leon Kelly, stylistically tricky to classify.

Leon Kelly was a talented Philadelphia painter who might have broken into the center ring as a major surrealist if his career trajectory hadn't been blunted by a shift in public taste and events beyond his control - World War II, for example.

It didn't help Kelly, either, that stylistically he was sometimes difficult to classify, and thus to promote. His best work is surrealist, yet he had the habit of drifting back into figurative painting, especially magic realism, which is easier to read, and more entertaining besides.

Kelly's surrealism was usually of the more abstract, mystical variety, as opposed to the hallucinatory images produced by painters such as René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. His work isn't as singular as theirs, nor does it usually provoke the instant recognition one associates with other big-name surrealists.

Kelly, who died in 1982 at age 80, is a painter worth knowing, yet his last significant show here took place in 1967 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he taught for a dozen years.

Thanks to Gratz Gallery & Conservation Studio in New Hope, Kelly is back in the public eye, in an exhibition of more than 100 oils that represents all the phases of his long career.

The show is the larger portion of a cooperative venture with Francis M. Naumann Fine Art in New York that aims to revive Kelly's reputation, which peaked in the 1940s and has languished since he died.

While the paintings at Gratz cover his full career, they emphasize the early years and, consequently, include many figurative pictures. Naumann's selection of 34 paintings and 17 drawings concentrates on surrealism.

Kelly's career is an instructive study in the evolution of a young painter's aesthetic during the early years of modernism. In the Gratz show, we first encounter him as a student at the Pennyslvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which he attended from 1922 to 1926.

There he studied with Arthur B. Carles, Philadelphia's most prominent and influential modernist. Despite his firm grounding in the academic tradition, evidenced by two standing male nudes, Kelly was attracted to more avant-garde currents.

As a young artist, he kept one foot in each camp. The influence of Cezanne, Picasso, and Matisse is evident in some paintings from the late 1920s and early '30s. In these, Kelly is testing different styles to see if any are comfortable.

Another American surrealist and a contemporary, Arshile Gorky, did much the same during the 1930s, working his way through the modern masters until an individual voice finally emerged in the 1940s.

Kelly was different in one noticeable aspect; he never abandoned tradition, but found ways to restate classical themes in contemporary terms. While living in Paris from 1926 to 1930, he copied Old Masters in the Louvre, a seemingly incongruous activity for a painter working in the hotbed of modern art.

His devotion to figurative painting and classical themes from mythology emerges most dramatically in a group of paintings featuring the goddess Venus painted in the late 1950s and early '60s.

Gratz is showing one of them, Venus Conquering Mars, in which a muscular, foreshortened God of War dallies with a surprisingly asexual Goddess of Love. These evocations of classical mythology are precisely rendered but juiceless and airless. The more demonstrative Triumph of Mars is closer to an Old Masterish ideal.

Kelly found his true calling in the abstract and sometimes bizarre and alien variety of surrealism associated with painters such as Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Roberto Matta, and Gorky.

The surrealist paintings of this kind at Gratz suggest why Kelly's art didn't generate broad popular appeal. A painting like The Messenger/Man with Kites of 1943 is difficult to embrace. An eerie figure with an attentuated arm, draped in what resemble the halves of an exotic seed pod, strides across a desolate, forbidding landscape.

Other paintings are composed of spiky forms that look like randomly assembled insect parts. Colors are sometimes harsh, while pictorial light is frequently dark and foreboding, as it is in The Messenger. Kelly's fantasies are not only personal but also generally ominous, even when, as in Lunar Encounter with a Child of 1958, he adds vivacity to his palette.

The trouble is that by 1958, surrealism was long dead in America, where, as a European import, it never caught fire. Kelly had the good fortune to hook up with Julien Levy, America's leading dealer in surrealists, in 1940, but that association never fully developed to the artist's advantage.

After the war, the world art capital shifted from Paris to New York, and abstract expressionism, an American movement, supplanted surrealism as the cutting edge. Levy closed his gallery in 1949, and Kelly's window of opportunity effectively closed.

Yet he went on painting as he had, only by now, after years in Philadelphia, he was living on Long Beach Island, which remained his home until he died. Some people have theorized that the strange bird and insect images that appear in many paintings were inspired by creatures Kelly observed near home.

The show contains a few other paintings that represent a more lyrical and poetic aspect of surrealism and that apparently relate to living on the beach. Sea Plants and Scissors and Seascape with Ladder, though small, are two enchanting examples. Mallorcan Mountain of 1960 also communicates a more gentle spirit, through its softly rounded forms and less confrontational colors.

I have not seen the Naumann portion of the exhibition, but I expect that later surrealist paintings hang there. A book published in connection with the exhibition illustrates several powerful late works, such as Levitation of Silvia of 1964, which is in the show, and particularly Bathers at Loveladies of 1972, which unfortunately is not.

The Gratz show is a tightly packed installation in an impossibly small space - even the stairway to the second floor is hung on both walls - that is too heavy on early work to offer a balanced retrospective.

Kelly is well-represented at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which holds five paintings and 20 works on paper (seven pieces are long-term loans) and at the Pennsylvania Academy, which owns four works. The Gratz show suggests that it's time one of these museums organized a proper retrospective, because Kelly certainly deserves the exposure.

Art: Leon Kelly's Back

"Leon Kelly - An American Surrealist" continues at Gratz Gallery & Conservation Studio, 30 W. Bridge St., New Hope, and at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, 24 W. 57th St., New York, through June 5. Gratz hours are 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays and noon to 6 p.m. Sundays. Naumann hours are 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays. Gratz information: 215-862-4300 or www.gratzgallery.com. Naumann information: 212-582-3201 or www.francisnaumann.com.

EndText