On the subject of race: Exhibit opens at the Franklin

BILAL QAYYUM sometimes causes confusion. Although he's black, with two black parents, he is often mistaken for white. The tall, silver-haired man with almond-colored skin is well-known in Philadelphia's African-American community as founder of the Father's Day Rally Committee. But to some white Americans, Qayyum, 62, looks just like them.

BILAL QAYYUM sometimes causes confusion. Although he's black, with two black parents, he is often mistaken for white.

The tall, silver-haired man with almond-colored skin is well-known in Philadelphia's African-American community as founder of the Father's Day Rally Committee. But to some white Americans, Qayyum, 62, looks just like them.

And at times, he said recently, a white person has made critical comments about African-Americans to him. Once a white man told him that Native Americans deserved reparations, but not black Americans.

"Really?" Qayyum responded. "Well, I'm black and I work for reparations."

"You're black?!" was the man's startled reply.

Local author Lise Funderburg, who wrote "Pig Candy" and "Black, White and Other: Biracial Americans Talk About Race and Identity," also has had her racial identity taken for granted.

She has fair skin and straight hair and is generally assumed to be white. But she is the daughter of a white mother and an African-American father.

Funderburg considers herself "mixed-race" rather than "bi-racial."

"While I respect the often-zealousness of people who are advocating for everyone who has a mixed-race identity to identify as mixed race, that sometimes oversimplifies how we each wear our identity in day to day life," Funderburg said.

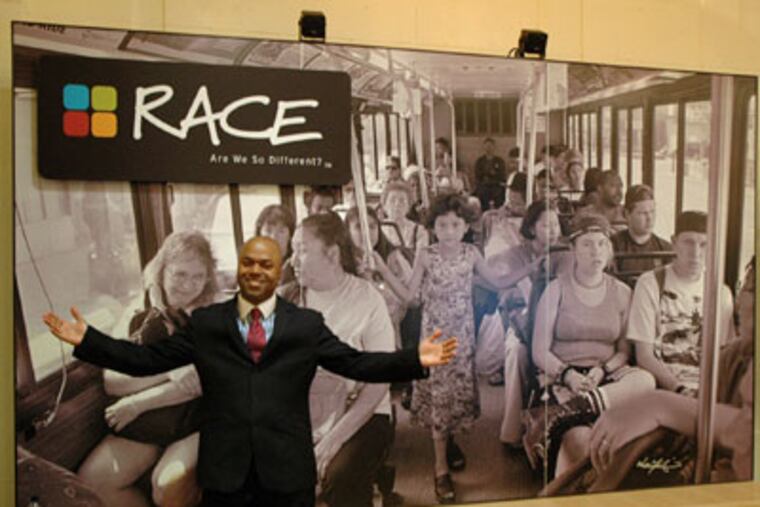

The idea of race and questions of racial identity are being highlighted in an exhibit that opened Saturday at The Franklin.

"Race: Are We So Different?" is a project of the American Anthropological Association and was created by the Science Museum of Minnesota. It will remain at The Franklin through Sept. 7.

The exhibit investigates the history of the concept of race and points out that science tells us that biologically, race doesn't exist.

The anthropological association commissioned the exhibit as part of its Race Project that was designed as a public education program "to promote a broad understanding of race and human variation."

The Race Project also has reached out to school teachers to use the traveling exhibit and an interactive Web site (www.understandingrace.org) as a way to "teach race and unlearn racism."

Throughout the interactive exhibit, the point is made that the idea of race was invented as a social and political construct.

One scientist viewed on several displayed videos said the concept of race was created to justify both the enslavement of African-Americans and the removal of Native Americans from their lands.

"Race is so deeply embedded in our lives it appears to be the natural order of things," Yolanda Moses, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Riverside, said in an interview with the Daily News. "We must challenge that notion with all the power of our science and society." Moses co-chairs the Race Project's advisory board.

Another anthropologist, Janis Hutchinson from the University of Houston, echoed Moses. "From a biological perspective, there's no such thing as race. Some 99.9 percent of the genes people [described as being of different races] are the same. There's no collection of traits that all people of a certain race have. What we're talking about is a social idea of race."

At a preview for the media Wednesday, Dennis Wint, The Franklin president and CEO, said that education and race "are two crucial issues for Philadelphia." The museum is hosting the exhibit to continue its role of fostering discussion of critical issues. The Franklin wants as many people as possible to see the exhibit, so it is included in the regular museum admission fee.

At the exhibit, visitors learn that we are all from Africa, because scientists discovered long ago that the ancestors of every human being on earth can be traced back through mitochondrial DNA to a woman in east Africa.

The exhibit also shows that race has nothing to do with skin color, which developed as an evolutionary response to the geographical location of one's ancestors. People of all so-called "races" can have dark skin if their ancestors originated from near the equator - from people currently living in Africa to people in India, Australia and the Pacific islands.

And it may surprise some white Americans to know that scientists at one time also categorized white Europeans as three distinct races: "Teutonic, Alpine and Mediterranean."

The exhibit also spotlights how race is experienced in everyday life - both past and present.

For example, miscegenation laws were passed that not only prohibited African-Americans and whites from marrying, but also banned marriage between whites and people of Japanese, Chinese and Native American descent.

As part of the exhibit, visitors will see videos of people discussing how they have been treated because of skin color or presumed racial identity.

And historical accounts of the experiences of various ethnic minorities are often horrifying.

Take, for instance, the story of an Inuit boy from Greenland named Minik.

In 1897, when Minik was 7 years old, Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary brought him, his father Qisuk and four other Inuit from Greenland to the American Museum of Natural History in New York "to be studied" by scientists there.

Peary had promised to return them to Greenland but after arriving in New York, four of them, including Qisuk, became ill and died. Minik was adopted by a museum official and his father's bones were "de-fleshed" and added to the museum's collections.

Years later, Minik would say: "They had used me for what they wanted; they had stolen my father's bones for their science. They didn't want me anymore and it was too much trouble to take me back."

Then there's the story of Wong Kim Ark, who became the subject of a United States Supreme Court decision.

The Chinese-American was born in California in 1873 and spent most of his life there. In 1890 he visited China and returned to the United States, but after a second visit in 1985, he wasn't allowed to return home to the U.S.

The Supreme Court ruled in 1898 that the 14th Amendment of the Constitution guaranteed citizenship rights to all persons born in the United States and not just to persons of a particular race.

But it wasn't until 1924 that Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act which made Native Americans full citizens.

And then there's the story of George McLaurin, an African-American who was admitted to the University of Oklahoma to earn a graduate degree in education, but was forced to be segregated from the other students. He had to sit in a chair in the hallway outside the classroom, eat at a separate table in the cafeteria and study at an isolated desk in the library. In 1950, the Supreme Court invalidated the segregated seating, saying it interfered with his "ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and in general, to learning his profession." *