You won't like what Eduardo Galeano has to say.

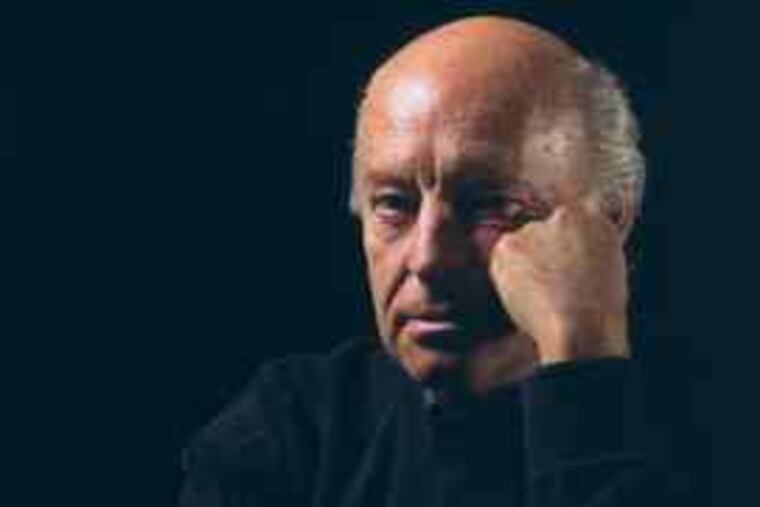

The Uruguayan author, who read from his new book, Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone, June 2 at the Free Library of Philadelphia, is the Superman of social critics, having spent his 40-year career reminding the world of the injustices committed in the name of freedom.

Galeano, 68, has a simple thesis: First World nations have become so obsessed with defending the freedom of the market, they have forgotten its human cost.

The belief that the world's major powers have become wealthy without exploiting and impoverishing millions of people elsewhere - in Galeano's words, that "wealth is innocent of poverty" - is a fantasy, he said.

His unassuming manner belies the ferocious wit he unleashes in his writing. One imagines a roaring lion, a terrifying Old Testament prophet, not such a gracious gent. Speaking in his Rittenhouse Square-area hotel room on the eve of his reading, he said that "the freedom of trade is the freedom of money, which implies jails for persons or for countries."

Globalization, Galeano has written, is a smoke screen used by the world's richest countries to impose economic power on the Third World.

Surely he's crazy. Definitely an extremist. Possibly dangerous. Yep, we don't like to hear what Galeano has to say about us.

Galeano, who dropped out of high school at 16, turned to writing only after he failed at becoming a pro soccer player. (His book about soccer, Football in Sun and Shadow, is among Sports Illustrated's top 100 sports books of all time.)

His more than 40 books have been required reading for progressives, but he became a celebrity overnight in April, when Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez handed a copy of his 1971 classic, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, to President Obama.

Veins argues that for its entire history, Latin America has been in the grip militarily and economically of Europe and the United States. It's hardly beach reading. But within 24 hours of its appearance in Obama's hands, it rocketed from No. 54,295 on Amazon.com's best-seller list to No. 5.

For his troubles in writing Veins, Galeano was imprisoned in 1973 by a military dictatorship that took over Uruguay. He eventually fled to Argentina but didn't stay long. In 1976, when Jorge Videla took power in Argentina, Galeano's name was added to the death-squad lists. (He fled to Spain, returning to Montevideo in 1985.)

Mirrors continues a project Galeano started in his three-volume masterpiece, Memory of Fire (1982-86), which recounts the history of the Americas. It's a genre-defying work that combines poetry, narrative, fiction, journalism, social analysis, and political opinion to tell the story of all the peoples who have been sacrificed for our progress.

"I [recount] the unknown histories of all these people who make history but are not inside it; who have not been registered by official history," said Galeano.

"History is made from contradictions," he said, pointing out that historians simplify those contradictions by excluding anything that doesn't jibe with our self-image. Sadly, those anomalies are "made of flesh and blood."

They include the American Indians virtually wiped out by European settlers. And the Africans who "have been so important in building America," but whose own freedom was denied and whose history has been forgotten.

"We still know virtually nothing about Africa," Galeano said. "We know what Professor Tarzan told us about it. And he was never in Africa."

If memory constitutes who we are and defines our possibilities, those whose memories have been stolen have lost their very humanity.

Mirrors, Galeano said, was written "to recover the lost memory of . . . [peoples who have] been mutilated by racism, machismo, militarism, elitism, and the concentration of power in the few countries who own [the majority of wealth]."

Composed of one- or two-page vignettes, Mirrors covers a dizzying variety of subjects, from the practice of female genital mutilation to Molière and Kafka; from the status of women in ancient Egypt to Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, and Django Reinhardt; from Gauguin to the genocide in Rwanda.

Galeano writes that if 500 years ago domination was military, today it's exerted through an economic policy called globalization and enforced by local governments.

He notes how just a decade ago, American economists applauded Chilean strongman Augusto Pinochet for turning his country's economy around - conveniently forgetting the dictator's crimes against his people.

But Mirrors also deals with people forgotten in the developed countries.

"Take, for example, U.S. founding fathers Gouverneur Morris, who wrote the text of the Constitution, and Robert Carter," said Galeano. "They have been forgotten . . . because they had a position against slavery . . . 60 years before Lincoln."

One of Galeano's most damning charges is that while Americans are obsessed with personal morality, we conveniently forget all moral imperatives when it comes to the market economy. In a world obsessed with the free market, all other concerns must be justified according to its dictates.

In his 2000 book, Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World, Galeano cites a 1998 UNICEF report that found that "12 million children under the age of five die every year" from curable diseases. The report concluded that the struggle against child hunger and disease must "become the world's highest priority."

Galeano points out that the report makes its case not by appealing to morality, but by stressing the economic costs: UNICEF shows how these conditions will "cost some countries the equivalent of more than 5 percent of their gross national product in lives lost, disability, and lower productivity."

So, is Galeano still a crazy, dangerous extremist?

Some may still be turned off because he criticizes the United States. But others might find his argument trenchant and his moral vision clear.

"What I really think is the scandal is that . . . the United States attributes to itself the mission to decide who is democratic and who is not," he said. "This country has all my respect and my love, I tell you, but it has no moral authority to do it."

He said too many American politicians and intellectuals "think they have this mission to save the world.

"And I would really please beg them, 'Please, don't save me. I don't want to saved.' "