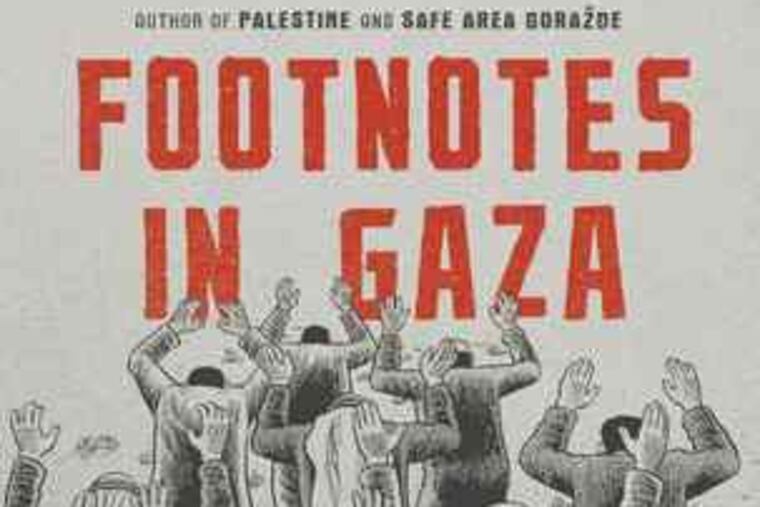

Serious story from Gaza in comic form

When people think about comic books, they think of Batman. That's fair: The vast majority of comic-book writing is about superheroes and other kinds of fabulous fiction. But the comic-book industry also has a long tradition of nonfiction works.

A Graphic Novel

By Joe Sacco

Metropolitan. 432 pp. $29.95

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Jonathan Last

nolead ends When people think about comic books, they think of Batman. That's fair: The vast majority of comic-book writing is about superheroes and other kinds of fabulous fiction. But the comic-book industry also has a long tradition of nonfiction works.

There have been comic-book tellings of events ranging from the Lindbergh baby kidnapping to the assassination of Lincoln to the war in Iraq. These are niche products - people don't buy the comic-book version of The 9/11 Report the way they do Ultimate Spider-Man - but they can be interesting and engaging nonetheless.

Joe Sacco has just released one such comic, Footnotes in Gaza. This behemoth tells the story of two incidents in the Gaza Strip in the 1950s, with Sacco serving as researcher, writer, and artist. As an artistic matter, it's a tour de force on every page. But as an exercise in historical narrative, it's a staggering, and in many ways surprising, work.

Noisy political commentary has always been a big part of the fiction branch of comics. In the '40s and '50s, comics propagandized about the Red Menace; in the '60s and '70s, they turned leftward, taking aim at Republicans and the American mainstream establishment. In the late 1970s, for instance, Captain America had a long-running feud with a villainous organization called C.R.A.P., headed by an American president who looked and sounded a lot like Richard Nixon.

Yet for all their liberal politics, when it came to nonfiction, the writers and artists were, for the most part, serious and fair-minded, almost always putting their political views aside in pursuit of objectivity.

That is, until George W. Bush. One of the smaller casualties of the Bush years was that even nonfiction comics gradually became more polemical, coming ultimately to resemble their politically outré fiction counterparts. A 2009 comic-book biography of Michelle Obama, for example, depicted Sarah Palin as a cackling harpy holding a bloody knife. Not even Lex Luthor gets that kind of treatment.

Yet Sacco turns his back on all of that in Footnotes. The project began in 2001 while Sacco was traveling the Palestinian territories with writer Chris Hedges. In the course of his reporting, Sacco heard tales about two Israeli "atrocities" in the Gaza Strip in 1956. On each occasion, the Israeli army was alleged to have entered a village and massacred scores of unarmed civilians.

There was very little hard evidence of the attacks, mostly just minor references to the incidents in a United Nations report. So in 2002 and 2003 Sacco returned to Gaza to assemble as much information as he could. While there, he kept company with shopkeepers and widows, terrorists and murderers, creating an oral history of the obscure events.

His sympathies clearly reside with the Palestinians. Yet Footnotes is the best kind of oral history: honest, candid, and simultaneously earnest and skeptical.

There's lots of art in Footnotes but little artifice. Sacco appears as himself throughout, drawing the scenes of his travels in Gaza. He shifts from the present back to 1956, and even as far back as 1948, when Israel declared independence. He tells how the Israelis displaced Palestinian refugees, how the Arab states cynically stoked Palestinian rage, how the United Nations unintentionally created a crippling welfare-state dependency among the Palestinians, who ultimately became both victims and aggressors.

With this backstory, Sacco then does his best to re-create, through scant historical records and interviews, what happened in the towns of Khan Younis and Rafah in 1956. In Khan Younis, it is alleged that Israeli soldiers went house to house, killing men indiscriminately. Sacco cites a U.N. report claiming a death toll of 275 lives. In Rafah, the Israelis staged a daylong military screening operation designed to separate militants from civilians, yet somehow, again, according to the U.N., 100 Palestinians wound up dead.

Because Footnotes is largely oral history, accounts of the events differ. But rather than forcing narrative reconciliation, Sacco plays it straight: He quotes his interviewees exactly, even pointing out conflicting stories. And - here is one of Sacco's great strengths - he is bluntly noncommittal about the reliability of any of his subjects.

One of Sacco's main characters, for instance, is a Palestinian terrorist named Khaled, who draws a salary from a no-show job with the Palestinian government's security forces. Sacco travels with Khaled but has no illusions about him. At one point, he asks Khaled why he is willing to accept payment for a job he doesn't do - a job, in fact, he often works against. Khaled responds that the government did try to cut off his salary once, but that he retaliated by threatening to kill someone: "If your salary is stopped . . . you shoot them. They know I've killed before. And killing is not a huge thing for me."

What Sacco is saying is plain enough: Here's the story, as well as I can figure it out, but pay attention to where it's coming from.

It's impossible to know with certainty what happened half a century ago in Khan Younis and Rafah. And Sacco would likely draw different political lessons from these stories than many readers might. But Footnotes in Gaza is nonetheless a triumph of reporting and honesty and that blessed commodity, good faith. With any luck, the rest of the comic-book industry will pay attention.