A different sort of Emily Dickinson, epileptic too

Among a spate of biographical and fictional works about Emily Dickinson pouring forth this year is Lives Like Loaded Guns, Lyndall Gordon's volcanic replay of the Dickinson family feud, the famous "war between the houses," which resulted in the most bizarre debut of any major figure in American literature.

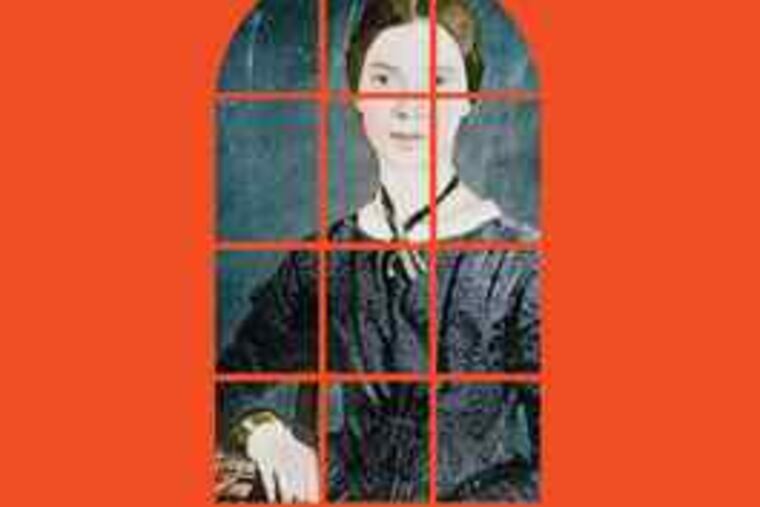

Emily Dickinson

and Her Family's Feuds

By Lyndall Gordon

Viking. 512 pp. $32.95

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Polly Longsworth

Among a spate of biographical and fictional works about Emily Dickinson pouring forth this year is Lives Like Loaded Guns, Lyndall Gordon's volcanic replay of the Dickinson family feud, the famous "war between the houses," which resulted in the most bizarre debut of any major figure in American literature.

In titling her novelistic biography, Gordon, a noted British biographer, has selected the first line of Dickinson's most elusive riddle poem, poem 754, "My Life had stood - a Loaded Gun," as the embracing metaphor for the powerfully controlled life she conceives Dickinson to have designed for herself. It serves, too, for the poems and letters the poet wrote, for a secret new disease Gordon has decided she suffered, for the ferocious two-generational family warfare that broke out posthumously over her poetry rights, and even for suppressed evidence in a subsequent lawsuit.

Volcanoes and gunshots erupt regularly in this action-packed drama. Only a biographer as skilled as Gordon could have written three books in one without forfeiting her readers' rapt attention. Loaded Gun begins with a bold reassessment of Dickinson's character. No longer a touch-me-not, within these pages she is brash, secretive, eruptive, scary, manipulative, and, of course, firmly centered in her brilliant imagination.

This Emily withdrew from the world not for her own safety, but to protect others. Gordon writes facilely yet engagingly of Dickinson's poetry, proposing, for example, that the most enigmatic poems "work" when a reader meets the poet's "demand for a reciprocal response, a complimentary act of introspection," and that "her dashes push the language apart to open up the space where we live without language."

Her portrait of the poet in later life gives way to the torchy, divisive love affair between Emily's married brother Austin and Mrs. Mabel Loomis Todd, who soon became the first editor of the poems after Dickinson's death. The remarkable romance, scarcely news to an American audience, is here repackaged to advantage Susan Dickinson, Austin's wronged wife and the poet's close ally. Sue's story, Gordon argues, has been eclipsed by an evil legend from Todd's poison pen.

Depicting Mabel's prized friendship with the never-seen, reclusive poet as bogus and cunningly cultivated through an exchange of messages and gifts, Gordon attributes nasty hidden meanings in Dickinson's cryptic responses, artful barbs to which Mabel didn't catch on.

In the last third of Loaded Gun, it is intellectual property that's at stake. The nefarious six-decade battle between Todds and Dickinsons over the publishing rights to Dickinson's nearly 1,800 manuscript poems, a grievous fallout of the love affair, is replete with a lawsuit and subsequent dueling volumes of poems and biography published by the daughters of the feud's principals.

Gordon handles the intricate telling well, provoking sympathy for Martha Dickinson and Millicent Todd, the two daughters left to carry on their mothers' anguished war.

Even an avid reader wonders, however, will this story ever end?

Actually, it hasn't. Venture to the Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Mass., now a museum, or onto the Web, and one finds supporters of one faction or the other still engaged in active sniping.

"My book is an attempt not to take sides," Gordon explained in a recent interview on National Public Radio's Fresh Air With Terry Gross. "I see my book as an attempt to strip the legends away." Alas, her attempt to right perceived injustices of past biographers is avidly partisan, and nowhere more apparent than in her portrayal of Mabel Todd, introduced as a comely young Amherst College faculty wife, but swiftly transformed into a "dressy adventuress" a few pages later.

Mabel merits a heated chapter titled "Lady Macbeth of Amherst," in which she is vilified as a liar, cheat, vixen, and calculating homebreaker. It's astonishing, after such viciousness, to discover that Gordon thinks highly of Todd's careful and skilled earliest editing of three volumes of Dickinson's poems and one of letters.

Now for the bomb in Emily Dickinson's bosom. Gordon posits that the poet's deepest secret was epilepsy. A few requisite "ifs" precede a survey of circumstantial indications, ranging from "the spasmodic rhythm of [Dickinson's] dashes" to the author's belief that two other family members had the disease, one of whom in fact did - Austin and Sue's son Ned - and one of whom did not - a cousin of Emily's father paralyzed by stroke.

Gordon combs scientific and literary resources about the illness, invigorates the life of the physician who treated the poet, and works epilepsy into a reinterpretation of several poems containing the word fit, despite Dickinson's use of the word as a verb. The shameful disease, Gordon argues, prevented Dickinson from marrying Judge Otis Phillips Lord, and accounts in large degree for her reclusiveness and for why she elected not to publish.

No evidence exists of Dickinson's epilepsy (although Ned's is recorded). So, the centerpiece of Gordon's supposition becomes an 1874 prescription for epilepsy she found in a 19th-century home medical manual, a formula of chloral hydrate, glycerine, and peppermint. Knowing Emily took glycerine in the early 1850s, Gordon mistakenly concludes it was prescribed for epilepsy, ignoring evidence that points in the poet's case to the nutritive glycerine being ordered as a remedy for suspected tuberculosis. The active ingredient in the 1874 epilepsy prescription was not glycerine, but rather chloral hydrate, given for convulsions, and not a medicine Dickinson is ever known to have taken.

Regrettably, the epilepsy theory is too sensational to be put back into its bottle. It has already added one more quack rumor to the many that swirl about this poet.

I wish that Gordon had included more in-depth discussions of entire poems instead of frugally selecting snipped lines to support her views. Certainly, the title poem, "My Life had stood - a Loaded Gun," deserved a full airing.