The truth about a truth-stretcher

They Died With Their Boots On, High Sierra, The Man I Love, White Heat . . . . Raoul Walsh, a man who reinvented himself a thousand times over, and who worked in the movie biz - first as an actor (in D.W. Griffith's silent classic The Birth of a Nation, no less) and then as a filmmaker - is the driving force behind each of these '40

The True Adventures

of Hollywood's Legendary Director

By Marilyn Ann Moss

University of Kentucky Press. 482 pp. $40

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Steven Rea

They Died With Their Boots On

,

High Sierra

,

The Man I Love

,

White Heat

. . . .

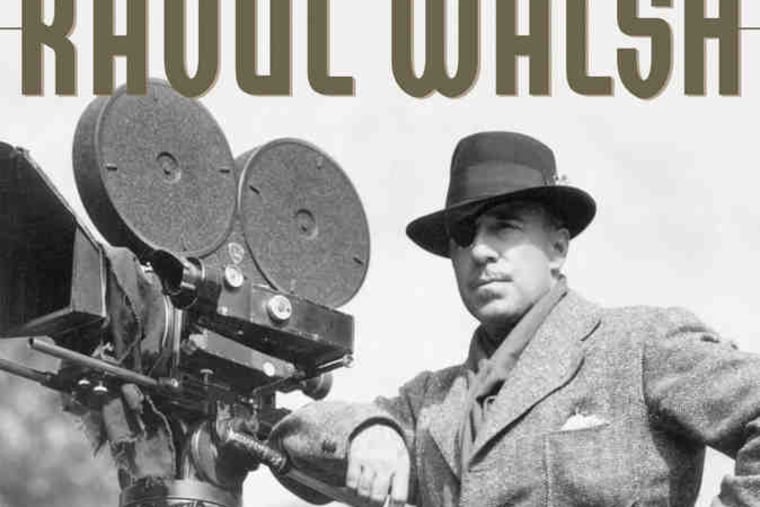

Raoul Walsh, a man who reinvented himself a thousand times over, and who worked in the movie biz - first as an actor (in D.W. Griffith's silent classic The Birth of a Nation, no less) and then as a filmmaker - is the driving force behind each of these '40s classics: a historically reckless reenactment of Custer's last stand (with Errol Flynn as the goldilocks general); a taut on-the-lam thriller with Humphrey Bogart; a "woman's picture" steeped in noir starring the glorious Ida Lupino; and one of the iconic gangster movies of the ages, featuring James Cagney in full psycho mode. If Walsh had made but these four pictures, his career would have been remarkable enough.

In fact, as Marilyn Ann Moss chronicles with dogged research, astute critical observation, and psychological insight in Raoul Walsh: The True Adventures of Hollywood's Legendary Director, the New York-bred son of Irish immigrants - born Albert Edward Walsh in 1887 - had his hand in more than 150 films during the six decades he plied his trade. He was the first director to use sound recording equipment on location - for the 1928 western In Old Arizona ("100% all talking Fox-Movietone Feature!" promised the theater posters). That film was notable, too, for a freak accident involving Walsh's jeep and a jackrabbit that left the director permanently blind in his right eye.

For the rest of his career, Walsh's view was monocular - like a cameraman's. Most of the time, Walsh, a snappy dresser (bespoke houndstooth jackets, riding pants, riding boots), sported an eye patch. Once in a while, he'd remove it and troop around the set with just a thin bandage across his eye.

Walsh also was the director who gave John Wayne his nom de screen (the Duke was born Marion Morrison) and his first starring role in 1930's The Big Trail. Walsh pulled some of the best work out of Bogart and Cagney. He put Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, and Rita Hayworth through their paces, working box-office magic in the process.

His daunting roster of motion pictures - tough-guy noirs, melodramas, war pictures, Westerns, even some musicals - was marked by technical innovation, by wit, by visual invention, and by a sense of the mythic. The mythic hero and the myth.

Moss, a film scholar whose book Giant delved into the life and work of director George Stevens, states her intentions from the get-go: to write a book about Walsh "that understands the man in a deeply truthful way."

This takes some doing, for Walsh, a fabulist and fabricator from his childhood on, was a master of what he called the "stretcher" - stretching the truth to its farthest reaches, and then beyond into the realm of fiction. So Moss approached Walsh's autobiography, 1974's Each Man in His Time: The Life Story of a Director, with considerable caution. (Telling detail: Walsh's original title was Here Lies the Truth, a devilish play on words.) "He looms larger than simply a player on the American scene and in the film industry," Moss writes. "He emerges as a one-man adventure show, presenting himself in one rollicking adventure, one tight spot, after another."

In his own autobiography, Moss points out, Walsh neglects to even mention the first two women he wed - the actresses Miriam Cooper (who hounded Walsh in court for decades after their divorce) and Lorraine Walker. Only Mary Simpson, an equestrian who was in her mid-20s when Walsh, then in his late 50s, made her his wife, is acknowledged. Apart from her beauty, it was Simpson's roots in Virginia horse country that Walsh connected to: Throughout his years in Hollywood, the director led a second life as a horse breeder and racetrack habitué. More often than not, it was the Racing Form he carried around a set, not a script.

He was also famous - exasperatingly so, to cast and crew - for walking away when the cameras started to roll. He'd wander off, listening to the lines of dialogue, perhaps, but seemingly uninterested. He'd already "seen" the whole thing in his head.

"Let's get the hell out of here!" the director was known to holler when a scene wrapped.

"Part humorous, part serious, the quip is the essential Walsh," Moss writes of her endlessly fascinating subject. "The man half in but at the same time half out the door, perpetually ready to bolt, to leap and walk quickly away, and to disappear into the dark corners of a soundstage where no one could find him but where everyone always knew he was just the same."