In this war, it's horse against machine

THE HORRORS of mechanized war, and a heart-warming story about the transformative power of a benevolent creature and boy's best friend.

THE HORRORS of mechanized war, and a heart-warming story about the transformative power of a benevolent creature and boy's best friend.

Who would even attempt to blend these two clashing pieces together in one movie?

Steven Spielberg, who certainly knows the ground, having made "Saving Private Ryan" and "E.T.," two obvious starting points for his visually dazzling "War Horse."

What he ends up with, though, is something distinctly different - a meditation on the 20th century transformation from pastoral to industrial, in the horrific context of World War One.

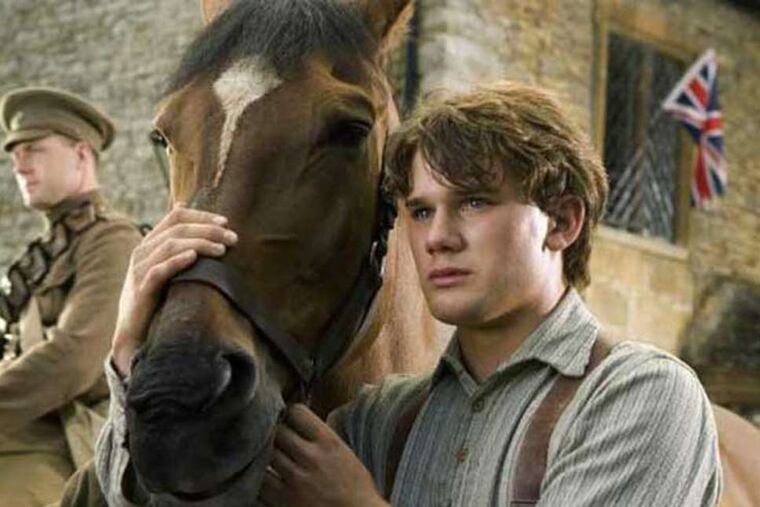

The old order is established in the film's early moments - a teen (Jeremy Irvine) on the English countryside falls for a a thoroughbred colt named Joey, repurposed as a plow-horse, heroically and defiantly pulling an iron blade through a rocky field to save himself and his tenant-farmer family (Emily Watson, Peter Mullan).

War separates boy and horse and both end up in the trenches of France, where the sprawling narrative tracks Joey as he's handed off from one handler to another (German, English, soldier, civilian) and pauses to show us the young man's horrid life in the muddy, deadly trench.

It's been noted that "War Horse" is as much a silent movie as "The Artist," and that's true - all the important information is conveyed in pictures, and Spielberg's best sequences show the contrast between brute and brute, industrial force.

There's a terrific scene of an 18th century cavalry charge encountering the 20th century machine gun. Fleeing horses, terrified and riderless, tell the tale.

Spielberg returns to this theme repeatedly, usually with great results.

Joey pulls a massive artillery gun up a hill as other animals fall, their hearts and lungs burst by the effort. A shell-shocked horse races through the trenches, confronting a tank amid the fog and gas - Spielberg at his most surreal.

And finally, in the movie's most persuasive emotional moment, soldiers observe a brief truce to free an animal from the barbed wire in No Man's Land.

It's a shame the movie does not end here. The narrative continues, with rolling resolutions that account for Joey's many human benefactors. It's a process of diminishing emotional returns.

The movie starts to feel like manipulation - there are moments when you wish Spielberg had never met composer John Williams, and the protracted prologue is where you feel it the most.

And of course there is the matter of Spielberg's sensibility. He's the movies' pre-eminant optimist. The contrast that he draws between the natural world and a world of man-made mechanized death precludes the idea that it is man's nature to go to war. We did so with stone tools, and when we didn't have stone tools, we used stones.

Still, who can quarrel with the impulse behind the final moments, horse and rider, alone in the fields, free and alive.