Secrets of the spy game revealed

It's entirely possible that the West owes its triumph in the Cold War, at least in part, to a dead rat.

It's entirely possible that the West owes its triumph in the Cold War, at least in part, to a dead rat.

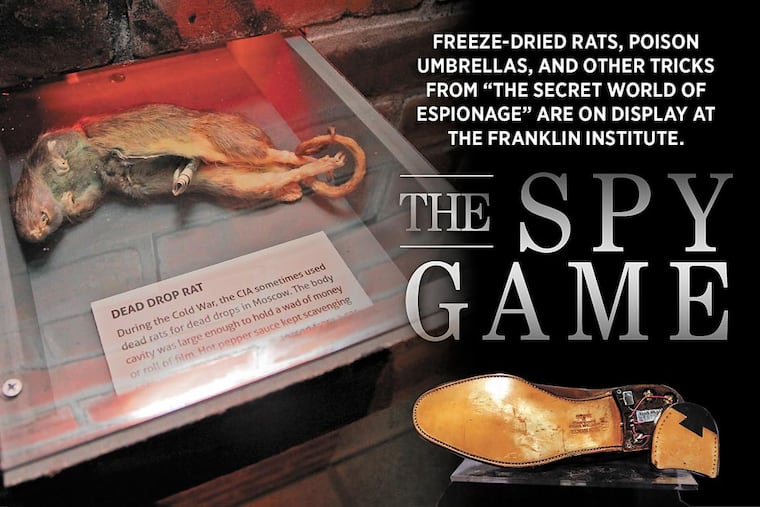

Freeze-dried, with a secret compartment built into its belly, the rat was one of many contrivances used by Central Intelligence Agency agents in Moscow and their handlers to pass communiques and other covert documents back and forth.

You can see one up close at the Franklin Institute's new exhibition, "Spy: The Secret World of Espionage," through Oct. 6. Anyone who has ever fantasized about being (or foiling) James Bond will revel in this rich, meticulously detailed show that tells the history of modern espionage through gadgets devised by spy agencies to find, follow, eavesdrop on, and off enemy counterparts.

The rat, for instance, was used to make so-called dead drops.

"How do you pass the information when your car is being followed wherever you go in Moscow?" said intelligence historian H. Keith Melton. "Make a quick right turn, and for the three seconds you're out of sight, you throw the rat to the sidewalk."

The method didn't fare well in field tests: The critters were quickly intercepted - by cats.

"So they began soaking the rats in Tabasco sauce," he said. "The cats didn't want anything to do with them after that."

Melton, coauthor with Robert Wallace of Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to Al-Qaeda, helped curate the show, which features 300 pieces from his private collection of more than 8,000 espionage gizmos. His fellow adviser was Gerald B. Richards, a retired FBI forensic scientist who specialized in analyzing spycraft tools for the bureau's counterintelligence investigations.

The Franklin Institute exhibition is divided by eras - World War II, the Cold War, the War on Terror - and organized thematically, with information on specific events and crises. One section charts how American authorities uncovered double agents such as CIA officer Aldrich Ames and FBI special agent Robert Hanssen, who sold out to the Russians in the 1980s.

A display includes an Enigma machine, used by the Nazis to send messages in a sophisticated cypher. It became a great weapon for the Allies after one was stolen by Polish soldiers and sent to England, where analysts were able to break the code. They did so only after developing Colossus, the world's first electronic digital computer that was fully programmable.

"The birth of the modern computer is thus tied to intelligence," said Melton, who maintains that the history of technological innovation always has been intertwined with the history of espionage.

A display on assassinations features the infamous Bulgarian umbrella, with a pneumatic mechanism that fired a ricin-treated pellet from its tip. One was used in 1978 to assassinate Bulgarian defector and BBC reporter Georgi Markov while he was waiting for the bus in London.

There's also the gas gun, a canister the size and shape of a cigar employed by the Soviets to deliver a lethal dose of prussic acid to the target's face.

"It was so effectively used by the Soviets," Melton said, "that an estimated 125 people were killed by it during the Cold War."

For all its exotic artifacts, "Spy" has a serious purpose, Melton and Richards explained: to separate fact from fiction and give the public an account of how espionage has helped augment foreign policy.

James Bond "is about fascination and seduction," Melton said. "In the real world, it's all about information and communication. But the real story doesn't always make for exciting movies."

While espionage figures in all wars, that is not its primary purpose, Melton said. "The purpose of good intelligence is to stop wars."

One display shows how, during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, spies helped the United States avert war, thanks to Soviet military intelligence officer Oleg Vladimirovich Penkovsky. A double agent, he informed the Americans of the Soviet emplacement of missiles.

"Penkovsky also told us a key fact," Melton said. "He told us that the Soviets were not prepared to start a nuclear war."

Knowing the Soviet Union would not risk a first strike, John F. Kennedy's administration played hardball and stared them down. The missiles were removed.

Or go back further, to the Revolutionary War and Longfellow's famous retelling of that pivotal moment: "One if by land, and two if by sea."

That was Paul Revere's method of sending intelligence about British troop movements in Charlestown, Richards said. One lantern in the North Church steeple would tell the colonists that the British were advancing by the land route, while two meant they were going across the Charles River.

Espionage often is depicted as a dirty business, Richards said, yet it is intimately woven into the very fabric of American history.