Weighing Walter White's goodness vs. badness

Who is Walter White, and why has he broken bad? What happens when you break bad? You become bad? Broken? Both?

Who is Walter White, and why has he broken bad? What happens when you break bad?

You become bad? Broken? Both?

But who gets to decide what's bad? What is bad, anyway?

Just a few philosophical questions to ponder as we wait for the return of AMC's extraordinary crime series, Breaking Bad, which will wrap up its sixth and final year with an eight-episode installment beginning Sunday at 9 p.m.

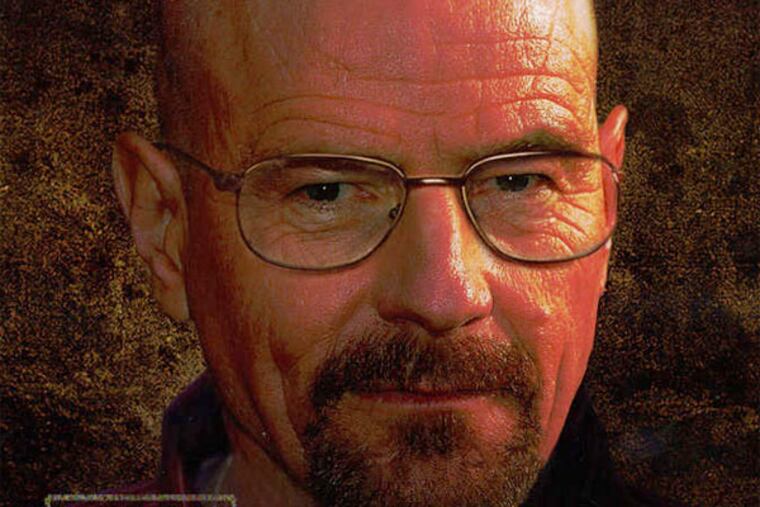

Writer-producer Vince Gilligan's creation stars Bryan Cranston as that most singular TV character, Walt, a geeky high school chemistry teacher-turned-drug kingpin.

Philosophical questions? Who said anything about philosophy?

Ask the editors of 'Breaking Bad' and Philosophy: Badder Living through Chemistry (Open Court, $13.97 paperback), a collection of 19 essays that pick apart and evaluate Breaking Bad from a wide range of philosophical, psychological, sociological, and literary approaches.

All the usual suspects are herein evoked, quoted, interpreted (and misinterpreted): Aristotle, Kant, John Stuart Mill, with a particular emphasis on the moderns, Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre.

Don't let the names scare you. The book is written for the general reader.

Academics usually study pop culture - say, reality shows or soap operas - merely to analyze how they reflect our values. The quality doesn't matter.

That's not the case with Breaking Bad, said David R. Koepsell who co-edited 'Breaking Bad' and Philosophy with Robert Arp.

"It's a tremendous work, almost cinematic," said Koepsell, who teaches at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. "I think it fleshes out the characters in a way few TV shows ever have done."

Koepsell said Breaking Bad was a profound morality tale that raised fundamental questions about our values, definition of success, and goals.

"Walt . . . represents a lot of the fears and anxieties that people living in modern America are facing," Koepsell said on the phone from Mexico City, where he spends summers. Joblessness, a bad economy, insecurity over the future seem to haunt Walt's world - as it does ours.

Montana State University's Sara Waller said Walt feels excluded from the American dream. He's a teacher, an occupation thoroughly devalued in a society that equates success with wealth. He never has enough money and is constantly humiliated by his students.

Walt goes on, of course, to amass great wealth.

"It's compelling to the audience that he is succeeding," Koepsell said. "We root for him. And he reaches what many people would consider to be the American dream."

But at what cost? Is being successful its own justification?

By the end of the fourth season, it's clear Walt is bad. Really bad. When did he cross the line?

Walt turns to crime in the first season, when he's told he has only six months to live. Terrified that his family could not survive without him, he begins manufacturing meth so he can leave them a nest egg.

Is he a bad person? Or does his motive - love - justify breaking the law and putting the public in danger?

Waller looks at Walt from Mill's utilitarian perspective, which teaches that we must try to achieve "the greatest pleasure for the greatest number of people," she said. It's a numbers game: Balance the good you're doing against the bad effects it may have. Sure, Walt's meth may kill a few people, but overall, it'd be worth it.

"Walt doesn't think he has long to live, and he figures that making meth for six months wouldn't do that much damage to society, but it would benefit his family greatly," she said.

Kant and most Christian theologians would disagree. For them, moral rules are absolute. You don't do anything that might harm your neighbor. Period.

Does Walt go bad when he commits his first murder? He does it to save a friend's life.

Or does he go bad when he discovers he's not really in the game for money, but for power?

Kimberly Baltzer-Jaray said Walt is best understood as an existentialist antihero in the tradition of Sartre and Albert Camus. Walt begins his journey a victim, put upon by his students, wife, and bank. He turns things around, thanks to meth.

"There is something positive about Walt taking control over his life," said Baltzer-Jaray, who teaches philosophy at the University of Guelph and King's University College in Ontario. "Sure, he's not going in the best direction."

Walt "is on a true path of self-discovery, of authenticity," Baltzer-Jaray said. "He figures out how to make the best, purest meth, and he gains recognition for his expertise, something he never had as a teacher."

What about all the horror he unleashes?

"I think he owns what he's doing," Baltzer-Jaray said. "He takes responsibility."

Koepsell disagrees.

"He's completely inauthentic," he said. "He has created around him a mythological world where he's the hero without once considering he always had alternatives."

Is redemption possible for Walt? Tune in to find out.