'Coolie Woman' documents brutality of indentured life

The United Kingdom abolished slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833, the act taking effect the next year. But British authorities found a workaround. They used "coolies" - Indian laborers recruited for fixed terms of at least five years - to meet the clamor for cheap labor on tropical plantations. Of the roughly million such emigrants, most were men seeking refuge from the famines that ravaged India in the 19th century.

Coolie Woman

The Odyssey of Indenture

nolead begins By Gaiutra Bahadur

University of Chicago Press. 312 pp. $35.

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Madhusree Mukerjee

The United Kingdom abolished slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833, the act taking effect the next year. But British authorities found a workaround. They used "coolies" - Indian laborers recruited for fixed terms of at least five years - to meet the clamor for cheap labor on tropical plantations. Of the roughly million such emigrants, most were men seeking refuge from the famines that ravaged India in the 19th century.

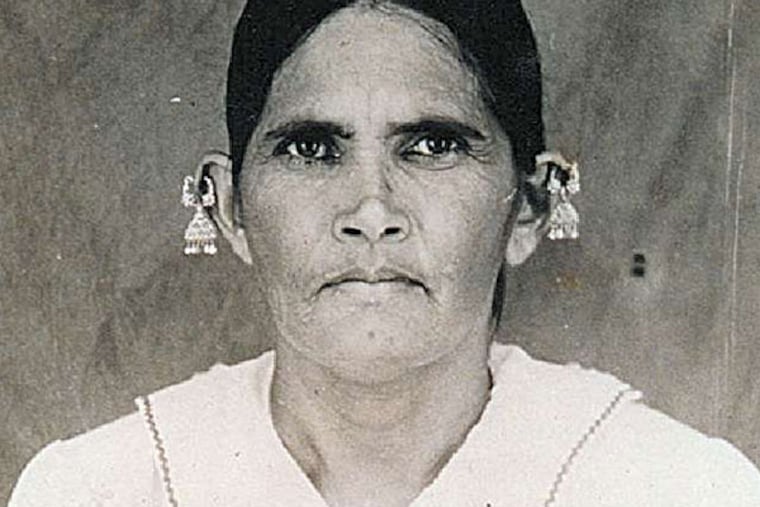

Hundreds of thousands of women also departed. Many were fleeing abusive families, and many were being trafficked by recruiters. Among them was Sujaria, an attractive Brahmin woman 27 years of age, who happened to be four months pregnant. She was transported to a plantation in Guiana. "On the line for husband's name" on her emigration pass was "only a dash," writes Gaiutra Bahadur, her great-granddaughter and the author of Coolie Woman.

Born in Guiana, Bahadur emigrated with her family to the United States at the age of six, and returned to her homeland in search of roots. Her quest has led to an epic and - given the passage of time - remarkably revealing account of love, intrigue, betrayal, and murder on the sugar plantations.

The journey was traumatic from the start, with the coolies crammed below deck, the women subjected to sexual predation. On one occasion, when their vessel docked at St. Helena, hundreds of coolies complained to a British official that the ship's surgeon, Dr. William Holman, had raped several women. Officials exonerated him after an inquiry, blaming instead the coolies' "tendency to exaggeration." Unsurprisingly, many of the women took protectors. Sujaria, who gave birth on board, was to form a lasting relationship with a married man.

By the time the ship disgorged its passengers on a faraway coast, they were utterly transformed: bereft of the places and people they loved and shorn of caste, tribe, and inhibition. "Like the slaves before them, they were an entirely new people, forged by suffering, created through destruction," writes Bahadur. The newcomers would remake their lives according to plantation norms: hard physical labor for subsistence wages, floggings (often on weekends so that by Monday they would have recovered enough to work), and, for the men, raging sexual insecurity.

Upon arrival, officials allowed couples to live together, and assigned every unattached coolie woman to a man on the same plantation. "All goes smoothly at first," explained a chief justice in Guiana. "After a time, however, the woman who is young, uninstructed and vain is attracted by a coolie who has been longer resident in the colonies and is able to offer her presents of silver and gold ornaments and to make her promises of wealth." She would leave the previous man, who became "a mark for the jeers and ridicule of his fellows" - often goading him into violent retribution.

In a typical case, on July 17, 1904, the husband of a woman named Lutchminia all but decapitated her with a cutlass. Her offence was abandoning him for another, which, Bahadur judges, was necessitated by coolie economics. Being paid at most two-thirds of what men earned, women needed to find better-off men, as Lutchminia's lover was, to support their families; moreover, the plantation had stopped paying her because she was pregnant. "With a son to feed and another child on the way, Lutchminia no doubt worried how they would all survive," Bahadur observes.

The gender ratio - Guiana had two female coolies for every five male - also enabled women to climb the plantation's social ladder, leaving behind men wracked with fury and despair. In 1871, an official study found that murders motivated by sexual jealousy were 90 times more frequent in Guiana than in India, and 142 times more frequent than in the two districts from which most of the coolies originated.

As Bahadur notes, patriarchal traditions alone do not account for the murders. The data point instead to the brutality of the coolie experience, as well as the impossibility of most of the men finding a woman of their own. The gender imbalance worsened their already precarious mental health, driving them also to suicide. Tellingly, "Fiji, where the percentage of women among the indentured was the lowest, also had the highest suicide rate," 20 times greater than in India.

Making matters worse, white plantation managers also availed themselves of coolie women. Significantly, Bahadur finds that such appropriations sparked a number of coolie revolts - which the authorities publicly attributed to anger over poor wages. An official noted that an 1896 strike, in which police gunfire killed five coolies, resulted from "the acting manager's having taken to himself the wife or woman of one Jungli," who was among those shot dead. Coolie legend tells a different story, which preserves honor: the manager had tried to rape her. She struck him and fled to the barracks, where Jungli and his friends valiantly defended her; hence the clash.

Coolie Woman could have used stricter editing: the author's personal reminisces are too ample to sit comfortably alongside the history. And Bahadur speculates via unanswerable questions that, on one occasion, extend across two pages. Nonetheless, by analyzing, with a rare combination of empathy and painstaking research, the love lives of coolies, Bahadur has shed unexpected light on the origins of sexual violence in many a dislocated community.