Building art, one Lego brick at a time

It's a few days before Saturday's opening of "The Art of the Brick" at the Franklin Institute and a few workers are still tidying up and maneuvering some of the show's 100 or so unique Lego constructions into place.

It's a few days before Saturday's opening of "The Art of the Brick" at the Franklin Institute and a few workers are still tidying up and maneuvering some of the show's 100 or so unique Lego constructions into place.

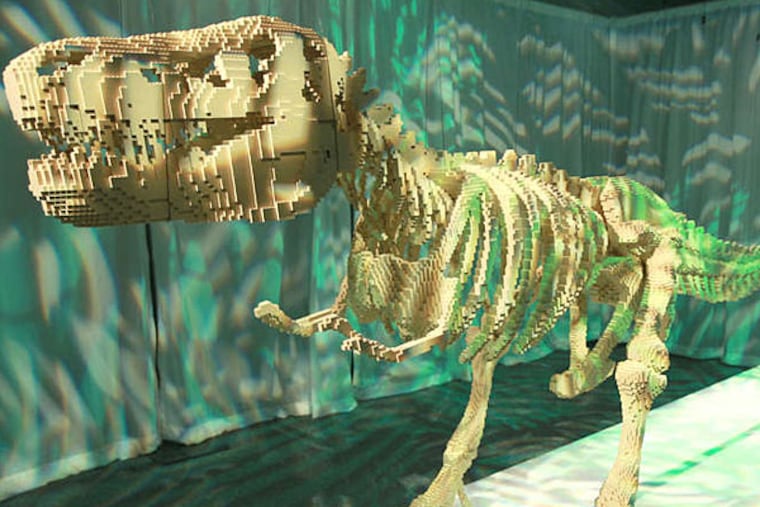

One worker is wandering about, artist's palette in hand, touching up colors where needed. The giant T-Rex - made of 80,020 snapped-and-glued Lego pieces - has already been hung from the ceiling. (It's a little too tippy to stand on its spindly legs.)

Paint is being slapped onto a pedestal where a special Philadelphia exhibit - a rendering of the Liberty Bell pieced and glued together from 31,753 little Lego bricks - will be displayed.

The bell's famous crack is filled in with the shiny Lego reds, blues, yellows and greens that every child knows.

"You see, I've fixed it," Lego master builder Nathan Sawaya said at a press unveiling Wednesday.

"The Art of the Brick" - constructions engineered by Sawaya - bills itself as the "world's largest display of Lego art." It will remain at the Franklin Institute through Sept. 6.

Larry Dubinski, the institute's president and chief executive, says a show of playful and ingenious Lego constructions is a good fit for his institution.

"For us, we see Legos in so many different ways," he says. "This one, obviously, is more of an art exhibition. But it's using what really has become one of the keys to creativity, innovation, engineering, math for kids of all ages."

Sawaya's exhibition, Dubinski says, seemed "a natural mix of bringing art and science together" - a mix the Franklin Institute is very comfortable with. A special Lego construction area, Ben's Brick House, will accompany the exhibition at the institute, allowing visitors - and not just children - to build their own constructions.

Sawaya, the talent behind the show, presides over a kind of Legolopolis, a wonderland of his original Lego works plus his Lego interpretations of familiar works of art - all made from the very familiar children's toy.

He designs and builds them all in studios in New York and Los Angeles - stocked with upward of four million bricks - and then sends them on the road. At the moment, in addition to Philadelphia, there is a show in Capetown, South Africa, one in London, and "a couple of others throughout the U.S., as well," says Jonathan Knight, who describes himself as the international director of the Sawaya enterprise.

"It means I run these shows around the world," Knight explains, standing beneath a translucent rendering of the great rose window from the Chartres Cathedral (17,842 bricks, including many teeny clear plastic caps used for Lego car headlamps).

Sawaya himself, a 41-year-old former New York corporate lawyer who gave it up more than a decade ago to follow his bliss, appeared at the institute for the unveiling of his special Philadelphia Liberty Bell, dubbed Fixed.

He's affable, if a bit stiff and focused on message: Legos are his art medium; children can become inspired; all of us need to release our creativity.

Creativity can also pay the rent. Sawaya's Lego works and commissions now sell for upward of $30,000. (Sawaya says at least one private commission sold for "six figures.")

"What I've learned over the past seven years of taking "The Art of the Brick" on the road is that art is not optional," he says. "Art is very important. It makes people happy. It makes people just better people. Creating art is what makes me happy, but I've also learned that creating art helps kids in school. Kids who have art in their curriculum actually have higher graduation rates and test scores.

"So I hope something like the "Art of the Brick" really inspires kids to go home and create. Really not just kids - I hope it inspires adults, as well."

Sawaya got his first Lego set when he was 5 and eventually built a Lego city in the living room of his childhood home in Oregon. He says he wanted to be an artist, but instead went to law school and practiced corporate law in New York - until he couldn't bear it anymore.

He worked briefly, he says, for the Lego Group, but now runs a completely independent operation as an artist working with Legos as a medium. Lego has certified him as a master builder, and he travels to Europe to meet with company executives now and then, but he is not under contract to the corporation, he says.

"It's a very good business relationship," is how he puts it. "It's a unique situation for an artist. A painter can go to different companies to buy paint. Only one company makes Legos and so I have a relationship where I am a very unique customer. I order hundreds of thousands of bricks every month. It's gotten to the point where I can shoot an e-mail and say 'Here's what I need,' and they ship it over."

He has a license from Lego that allows him to purchase bricks "in a nontraditional manner," and he takes "special pains to make sure Lego is represented properly" in written references. Beyond that, there's not much to it, he says.

"It's just respecting the brand, I suppose," he adds. "I hope it's a little of a mutual admiration society."

215-854-5594

@SPSalisbury